Click on the image to zoom

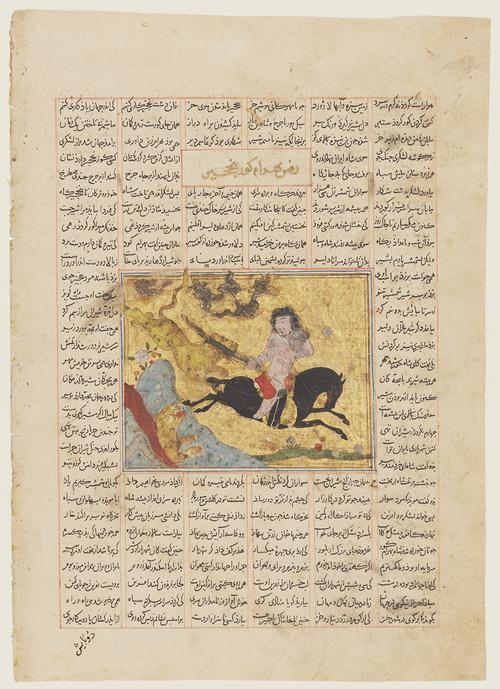

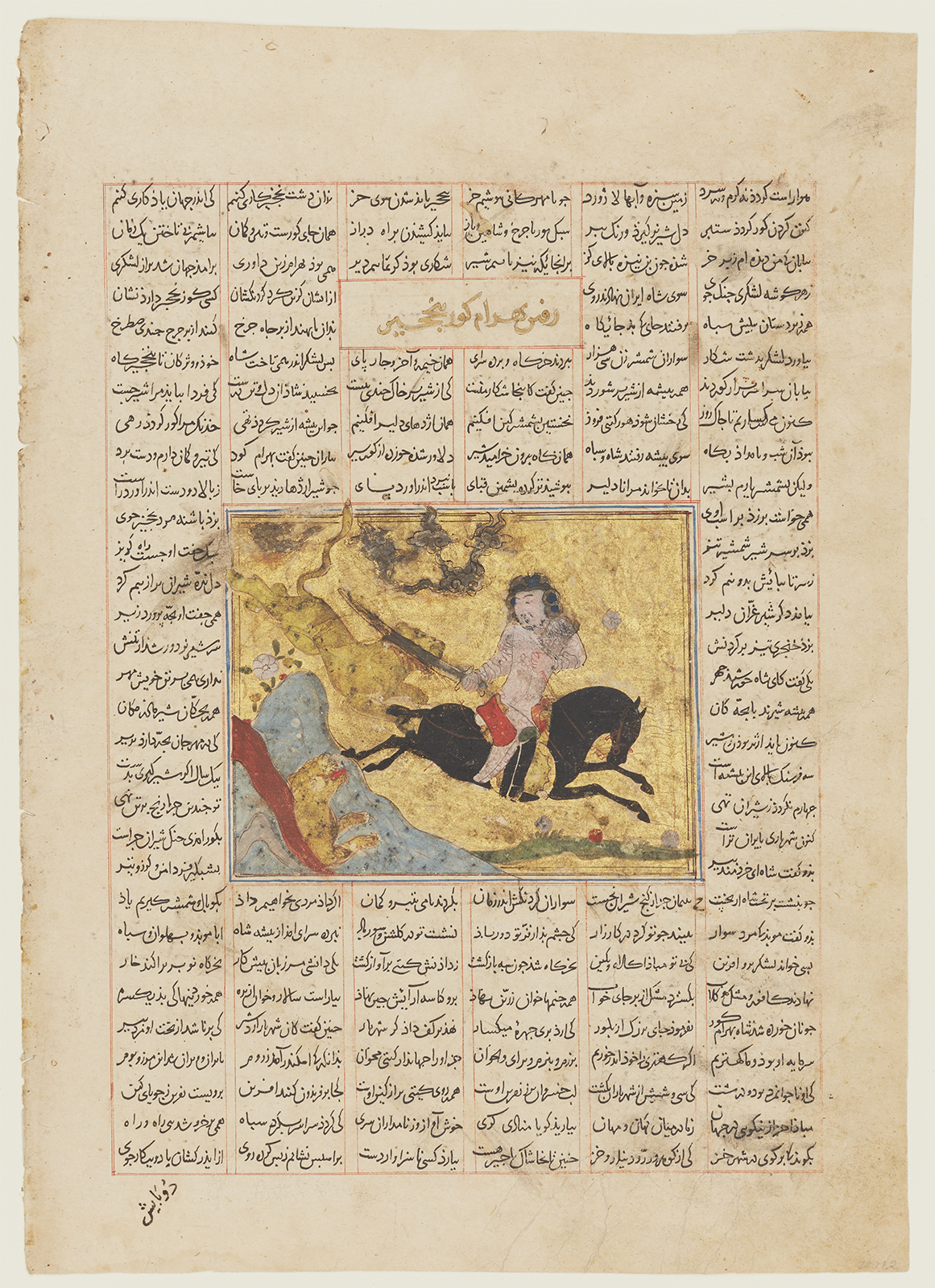

Bahram Gur Hunts, Slaying a Lion and a Lioness

Folio from a dispersed copy of Firdausi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings)

- Accession Number:AKM20

- Place:Western Iran

- Dimensions:30.8 x 22.1 cm

- Date:late 13th or early 14th century

- Materials and Technique:ink, opaque watercolour, gold, and silver on paper

This folio from the dispersed copy of the “Freer” Shahnameh (Book of Kings) depicts a classical Sasanian image of kingly power by illustrating an episode in the life of the Sasanian kings: Bahram Gur (r. 420–38).

Bahram V, “that great hunter”, is depicted in the midst of hunting lions (instead of the onagers—in Persian, gur—the source of his nickname). This adventure had begun with the king’s dispatching the male lion with an arrow to the heart; the beast roared mightily as it expired, alerting its mate. She herself lunged at Bahram, clawing him, but not preventing him from drawing his sword to slay her, too. As so often in Firdausi’s tales of Bahram, the hunt was followed by feasting and wine, and the inevitable inebriation. On this occasion, however, inebriation led to disaster and Bahram, aghast, prohibited the drinking of wine. But shortly thereafter, when wine also made possible the taming of an escaped lion, the king reversed his prohibition.

Further Reading

Often Bahram Gur is shown hunting with bow and arrow. Here, the image of the mounted king slaying a pair of lions in a mountainous landscape recalls Sasanian images in an entirely different medium: plates of precious silver, decorated in high-relief with a crowned figure hunting pairs of beasts. One splendid example is the 4th-century plate in the Hermitage [1]: a majestic figure of Shapur II (r. 309–79) on horseback, hunting a pair of lions. Of course, the two are dissimilar in material, figural style, and quality; even their functions are different, text-illustration as opposed to emblematic representation. Yet their fundamental subject, the valour and bravery of the Iranian king prevailing over dangerous beasts, surely endured in the Iranian imagination for nearly a millennium and must have served the Ilkhanid painter as an instinctive model.

Introduction to the“Freer” Shahnameh [2]:

The “Freer” Shahnameh (Book of Kings), now so widely dispersed, is the third [3] of the early iest surviving illustrated copies of the Persian national epic, the work of Abu’l-Qasim Mansur Firdausi (d. 1020). Composed around the turn of the 11th century, the Shahnameh conveys through 50,000 rhyming couplets the lives of 50 Iranian kings before the arrival of Islam. The name “Freer Small” reflects the fact that most of the manuscript (text-pages and 45 illustrations) has been in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC, for much of the 20th century.[4] The “parentage” of these folios has never been in doubt; they have long been known to come from this dispersed copy of the Persian national epic.[5]

In many ways, however, the “Freer” manuscript is unlike the other two with which it has for so long been grouped, the “First” and the “Second Small” Shahnameh manuscripts: it is neither small nor does it materially resemble them, apart from also being copied in six columns of text, and sharing a figural similarity with some illustrations in the other two. More significantly, the smooth burnished paper on which it was written and illustrated is very different from that of both the other “Small” manuscripts, and the internal characteristics of its paper-stock vary considerably even from folio to folio.

The illustrations, too, are differently treated: with few exceptions (“Furuhil Fights With Zangula,” AKM84, is one) they are squarish in shape (or occasionally stepped), usually displacing 12 lines of text and almost always centred over the inner four columns of text. The altered shape of most pictures gives the impression that figures in them are larger than actually they are.

Such material differences—folio-size, paper-stock, and the conception of the illustrations—all suggest a different place of origin for the “Freer” Shahnameh. Wherever in western Iran this copy of Firdausi’s great epic was made towards the end of the 13th century or very early in the 14th,[6] it was not in the same place, let alone in the same workshop, as were the “First” and “Second Small” manuscripts.

Like the four folios from the “Second Small” Shahnameh in the Aga Khan Museum Collection (AKM16, AKM17, AKM18, AKM85), the folios from the “Freer” Shahnameh fall into two groups. Two illustrate stories of legendary kings (AKM22, AKM84); the other two are episodes in the lives of two historical Sasanian kings: Shapur I (r. 242–70) (AKM21), and Bahram (Vaharam) V, Bahram Gur (r. 420–38) (AKM20).

— Eleanor Sims

Notes

[1] Dish: Shapur II on a Lion Hunt; period: Between 310 and 320; dimension: diam. 22,9 cm; The State Hermitage Museum, inv. no: S-253. http://www.hermitagemuseum.org/wps/portal/hermitage/digital-collection/08.+applied+arts/97900

[2] This writer has already suggested the alternative name “Freer 14th-Century Shahnameh”. See Sims, The Tale and the Image [a catalogue of historical and Shāhnāmah manuscripts and paintings in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art] (Volume XXV, forthcoming in 2019).

[3] The other two are the “First Small” Shahnameh and the “Second Small” Shahnameh.

[4] Marianna Shreve Simpson, The Illustration of an Epic. The Earliest Shahnama Manuscripts(New York and London: Garland, 1979), 351–68, reconstructs the original and notes 48 gaps, of which 41 might have had illustrations.

[5] See Anthony Welch and Stuart Cary Welch. Arts of the Islamic Book: The Collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982, 136–7 and Simpson 1979, Appendix 5, 383–96.

[6] “around 1300 in Baghdad” is an attribution largely accepted since 1979 (Simpson 1979, 273–80); it is no longer tenable. This was based upon information in the colophon of a Persian copy of Sa‘d al-Din al-Varavini’s Marzban-namah (in the Library of the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul, MS 216); the manuscript was completed in Baghdad on 10 Ramadan 698/19 May 1299 but has just three small illustrations

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.