Click on the image to zoom

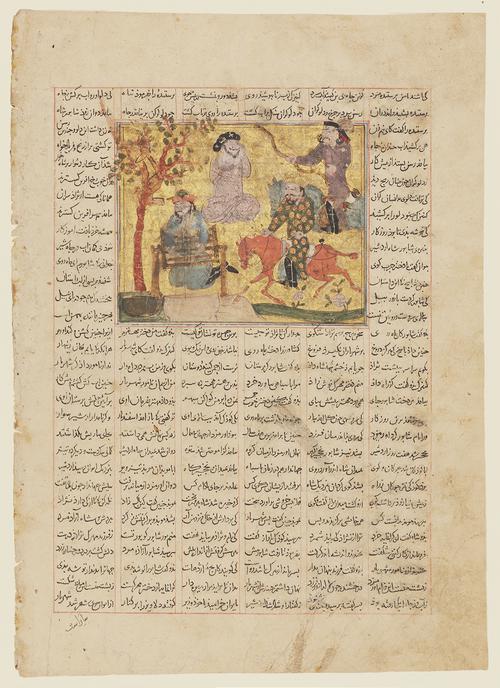

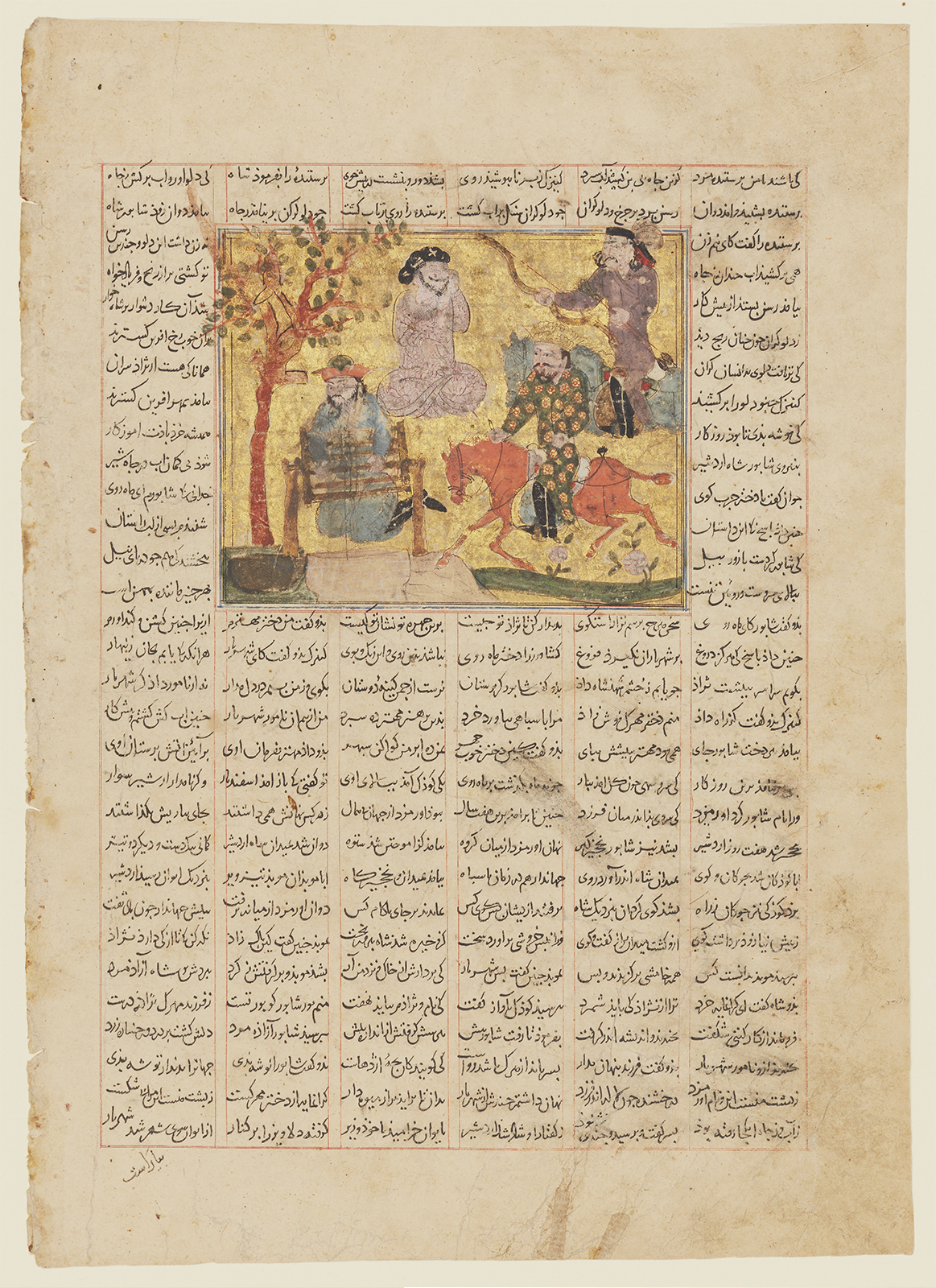

Shapur Sees the Daughter of Mihrak at the Well

Folio from a dispersed copy of Firdausi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings)

- Accession Number:AKM21

- Place:Western Iran

- Dimensions:30.4 x 21.8 cm

- Date:late 13th or early 14th century

- Materials and Technique:ink, opaque watercolour, gold, and silver on paper

This folio from the dispersed copy of the “Freer” Shahnameh (Book of Kings) comes from to the historical section of Firdausi’s great poem, and the life of the Sasanian kings: Shapur I (r. 242–70). It anticipates another iteration of one of Firdausi’s consistent sub-themes: the alliance of former adversaries in marriage for, among other reasons, the begetting of legitimate successors possessed of the divine farr [1].

The painting depicts the initial meeting of Shapur and the daughter of Mihrak, the low-born man who had looted the palace of Shapur’s father’s near Istakhr. Having come lately from hunting, Shapur drinks at a well after the maiden calls him by name and offers sweet water.

See AKM20 for an introduction to the “Freer” Shahnameh.

Further Reading

As Shapur drinks, the maiden, depicted in a pink lotus-flowered garment, sits and watches. At some past moment, she has been disfigured by the addition of a black beard and a mustache, and a peculiarly puffy black hat. Shapur in turn will marry this young woman at the well, tying his bloodline to Mihrak; their child will become Hormuzd I (r. 270–1). Shapur’s father Ardashir will ultimately come to praise this union, saying, “neither I, nor this country, nor my crown, throne, or army would enjoy good fortune unless my lineage were joined to that of Mihrak.”

Shapur’s own father Ardashir, first of the Sasanian line, had married the daughter of his predecessor, securing a union for political and dynastic motives.[2] Other alliances of former adversaries include Zal, the Iranian champion, marrying Rudabeh, descended from the Arab tyrant Zahhak; their son was the greatest of Iranian heroes, Rustam. Siyavush, the noble Iranian prince cut down before his time, had married Farangis, daughter of Iran’s greatest Turanian foe; their son Kay Khusrau became one of Iran’s greatest legendary kings.

The Aga Khan Museum Collection has four folios from the “Freer” Shahnameh, AKM20, AKM21, AKM22 and AKM84.

— Eleanor Sims

Notes

[1] Farr is Zoroastrian in concept and derives, linguistically, from the language of the Avesta (or Zand-Avesta), the Zoroastrian scripture: khvarenah or khwarenah (in Avestan, xᵛarənah). The word, and its significance, resonate throughout Firdausi’s epic: true kings have it, even when they are not accorded their true rank. Farr is evident to others, even in the most apparently humble of persons; those who falsely lay claim to the throne are perceived to lack farr and never achieve their aims. Moreover, kings who do not behave rightly or abuse their power may lose their farr and their position—sometimes, also, their lives. On farr, see the entry in the Encyclopedia Iranica: FARR(AH).

[2] Ardashir’s wife had been persuaded—by one of her brothers, exiled in India—to poison her husband, permitting her family to regain power in Iran. The poisoned container shattered; the plot failed; once again, a queen was threatened by death for treason but reprieved because she was pregnant with a potential heir. Ardashir’s vizier hid the fact of the pregnancy. The male child (Shapur) was safely born and safely hidden for seven years from his father’s knowledge until Ardashir, aging and without a male heir, complained of this to the vizier, who then revealed the happy news. In due course, Ardashir came to meet and educate his son, Shapur: “how to write in Pahlavi, how to hold a royal audience, how to ride into battle and confront his enemies, the protocols . . . of banquets and kingly generosity.”

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.