Click on the image to zoom

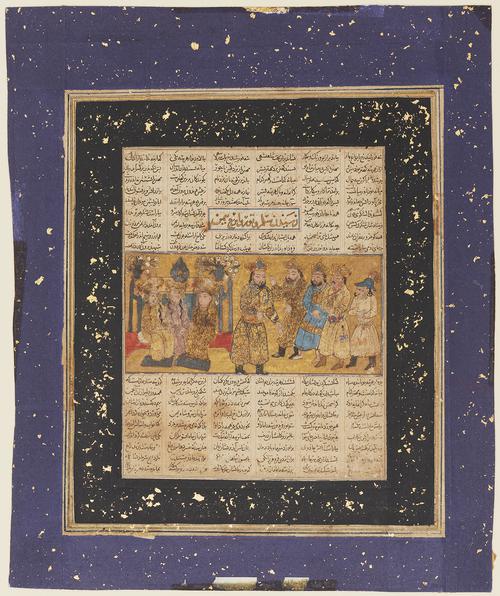

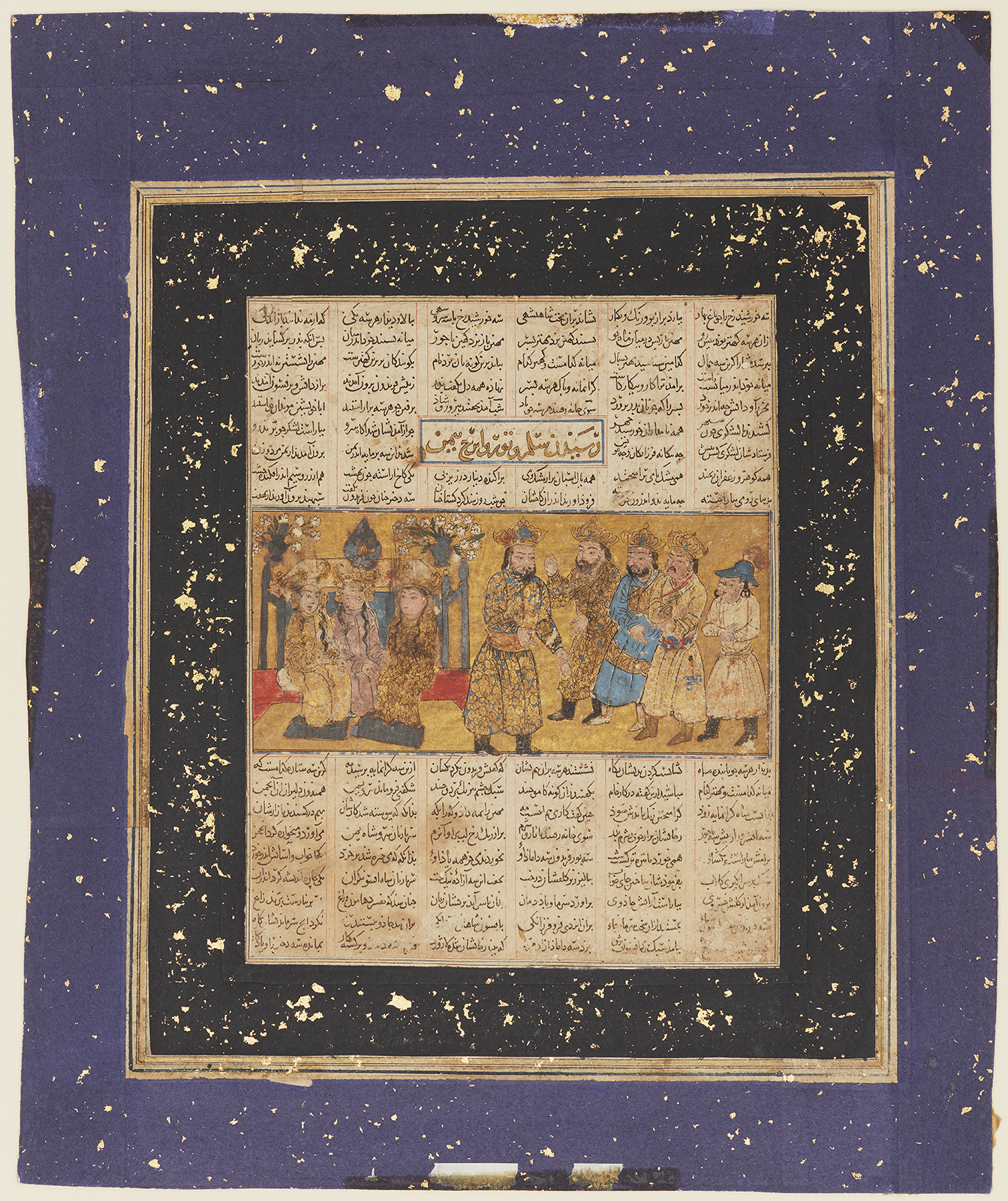

The Three Sons of Faridun at the Court of King Sarv of the Yemen

Folio from a dispersed copy of Firdausi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings)

- Accession Number:AKM19

- Place:Western Iran

- Dimensions:15.1 x 12.4 cm

- Date:late 13th or early 14th century

- Materials and Technique:ink, opaque watercolours, gold, and silver on paper

This folio from the dispersed copy of the “First Small” Shahnameh (Book of Kings) depicts the story of Faridun and his three sons at King Sarv’s court. The story belongs to the first section of the Shahnameh, containing tales of Iran’s mythical kings. In a row spreading across the entire width of the page are the protagonists of this episode. The wily King Sarv of Yemen stands in the centre. “Behind” him (to the left), are seated his three daughters, “radiant princesses” whom he wished to keep forever by his side. “Before” him (to the right) are the three sons of Faridun, suitors for the hands of the three princesses; they are accompanied by Faridun’s wise and discerning messenger, Jandal. All are richly dressed and crowned; only Jandal wears a cap, blue and trimmed with owl feathers [1].

Further Reading

This simple composition on a golden ground embodies several themes central to Firdausi’s poem. Perhaps most important is the continuity of Iranian kingship, in a world where Iranians and Arabs were neighbours. The second concerns the education of young people: to learn to conduct themselves well and politely, and also to be alert to potential dangers in significant situations. A third theme is literary: the classical device of three offspring from whom disaster may eventually arise.

The painting is placed in the middle of a page of six columns of text, three verses to a line; in this, it reveals its age, the six-column format being typical of the earliest of recorded Shahnameh manuscripts. No dated copy of Firdausi’s great poem is known from any earlier than the Hijri year of 614, or 1217.[2] Moreover, Shahnameh volumes with pictures do not seem to exist before late in the 13th century, after the Mongol invasion of the central lands of Islam and the subsequent establishment of a Mongol state in Iran, marking the beginning of the Ilkhanid dynasty.

Introduction to the “First Small” Shahnameh [3]:

The “First Small” Shahnameh, now dispersed [4], is one of the earliest of surviving illustrated copies of the Persian national epic. This vast poem was composed by Abu’l-Qasim Mansur Firdausi (d. 1020) around the turn of the 11th century—the end of the fourth Hijri century, when Iran’s pre-Islamic past was still within its collective memory, and “New Persian,” the language of the Muslim period, had become a flexible and poetic instrument now written in Arabic script. The Shahnameh recounts the “history” of 50 kings of pre-Muslim Iran, conveyed in more than 50,000 rhyming couplets. It begins with tales of Iran’s mythical kings; tales of its legendary and historical kings follow; the Shahnameh [5] concludes with the arrival of Islam.

The “First Small” Shahnameh, one folio from which is in the collection of the Aga Khan Museum, has a “companion” volume—called the “Second Small” Shahnameh; four illustrated folios from it are also in the Aga Khan Museum (AKM16, AKM17, AKM18, AKM85). None of these dispersed folios carries any indication of where or when either early manuscript was created.[6] At present, however, the most likely attribution is to some centre in western Iran, and no earlier than towards the end of the 13th century. One visual clue to this date is the bird-feathers—seen in some illustrations; they were worn on Ilkhanid male headgear to distinguish rank and position.

Corroboration for a place of execution arises from new research: the quality of the paper of both the “First” and the “Second Small” Shahnameh manuscripts.[7] It is entirely unlike the superb paper manufactured in the capital city, Baghdad, both before and after the Mongol conquest of 656 (February of 1258), and where the Ilkhanid sultans continued to commission fine volumes of the Qur’an.

— Eleanor Sims

Notes

[1] The owl feathers in Jandal’s blue cap offer corroboration for a date. After the Mongol conquest, Ilkhanid male headgear distinguished rank and position by the feathers of different birds.

[2] Angelo Michele Piemontese, “Nuova luce su Firdawsø: uno “Såhnåma” datato 614h/1217 a Firenze,” Annali dell’Istituto Orientale di Napoli, 40 (n.s., XXX)(1980): 1–91.

[3] The term coined by Ernst J. Grube in Muslim Miniature Paintings from the XIII to XIX Century from Collections in the United States and Canada (catalogue of an exhibition at the Cini Foundation, Venice, and Asia House, New York City), (Venice: N. Pozza, 1962), 22–8.

[4] 82 folios, of at least 116, in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin: A. J. Arberry, Mujtaba Minovi & Edgard Blochet, The Chester Beatty Library. A Catalogue of the Persian Manuscripts and Miniatures, ed. J.V.S. Wilkinson (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, 1959), 11–16; Marianna Shreve Simpson, The Illustration of an Epic. The Earliest Shahnama Manuscripts (New York and London: Garland, 1979) especially Appendix 3, 369–76, and Appendix 5, 383–96.

[5] After the mythical section, the Shahnameh contain stories of its kings of legend. It finishes with accounts of its historical kings, those of the Parthian and Sasanian dynasties (247 BC–224 AD and 224–651).

[6] “Around 1300 in Baghdad” is an attribution largely accepted since Simpson’s publication of 1979, 273–80; it was based upon parallel information in the colophon of a Persian copy of Sa‘d al-Din al-Varavini’s Marzban-namah (in the Library of the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul, MS 216). This manuscript was completed in Baghdad on 10 Ramadan 698/19 May 1299, but has just three small illustrations; for this reason, as well as the observations reported in Note 5 below, it is no longer tenable.

[7] Paper-research conducted by Helen Loveday, included in Eleanor Sims, The Tale and the Image [a catalogue of historical and Shāhnāmah manuscripts and paintings in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art] (Volume XXV, forthcoming in 2019).

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.