Click on the image to zoom

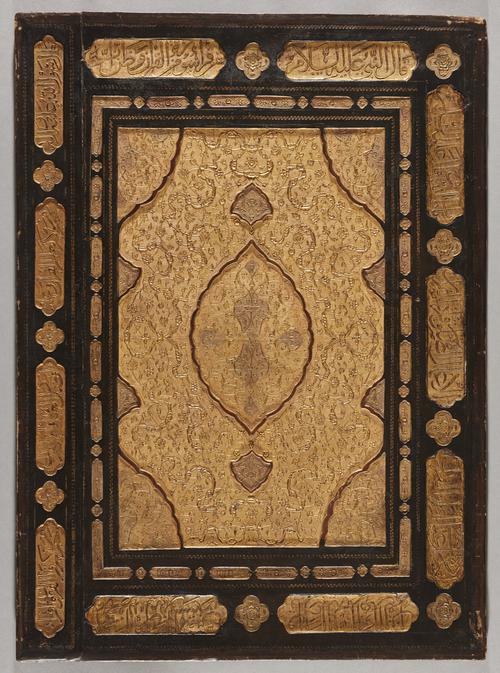

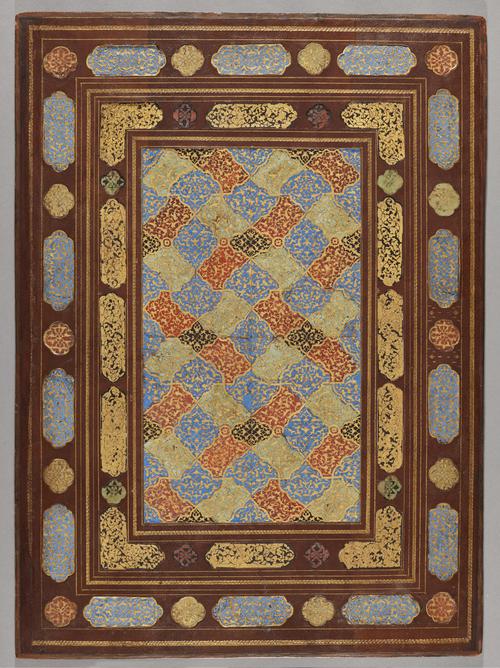

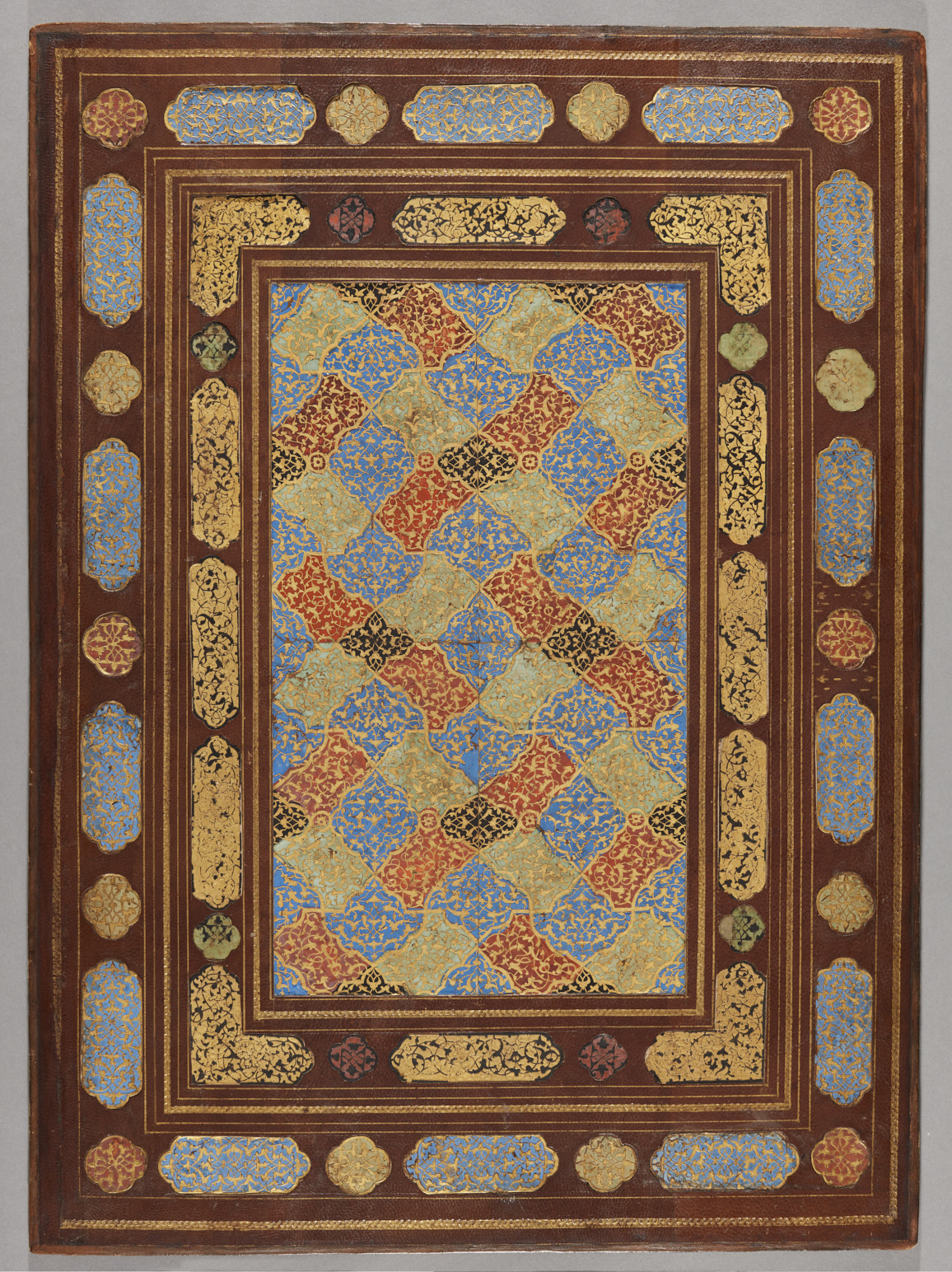

Upper cover and front doublure of a Qur’an binding

- Accession Number:AKM386

- Place:Iran

- Dimensions:50.5 × 36.7 cm

- Date:ca. 1550–75

- Materials and Technique:leather, pasteboard, coloured paints, and gold; pressure-moulding, filigree

Created for Qur’an copies as early as the 9th and 10th centuries, Islamic bindings typically consisted of an upper cover at the front, a lower cover at the back, an envelope and fore-edge flap covering the edge of the pages, and a spine covering the binding edge. This upper cover and front doublure (interior lining) in the Aga Khan Museum Collection likely belonged to an illuminated Qur’an whose text was the work of a master calligrapher.[1] The lower cover and attached spine, envelope, and fore-edge flap must be in another collection.[2] When a manuscript was being produced for the sultan’s book treasury, as an endowment to a mosque founded by a member of the royal family, or as a gift to a foreign ruler, the binder would pour all his art and skill into the binding. In this way, the binding had two primary purposes: to protect the pages contained within and to serve as an outer reflection of the book’s content.

Further Reading

That this binding once covered a Qur’an can be determined by its Arabic inscriptions. Eleven cartouches around the broad border on the upper cover of the binding contain advising readers of the benefits of reading the Qur’an.[3] Inscribing hadith or verses from the Qur’an in the borders of Qur’an covers and doublures was a widespread tradition, although not a feature of all Qur’an bindings. The central field of this upper cover contains a medallion with pendants and corner-pieces. These are filled with rumi motifs and flowers on scrolling branches, while the spaces between the medallion and corner-pieces are filled with large flowers on scrolling branches, overlaid with a second design of cloud motifs in high relief. All the motifs are gilded. The narrow border is decorated with floral motifs inside cartouches. At the centre of the doublure is a leather filigree motif cut in a lattice pattern and painted in gold. The ground of the lattice apertures is painted in black, orange, cream, and blue, and decorated with arabesque motifs cut from leather and painted in gold. Cartouches around the inner and outer borders of the doublure are decorated with filigree leather arabesque motifs.[4]

Similar bindings can be found on manuscript Qur’ans with illuminated pages dating from the period 1550–75. The page design, layout, colours, and motifs used in the illumination as well as the names and cognomens of the calligraphers suggest that this group of Qur’ans was produced in Iran during the Safavid period by itinerant artists who moved between Tabriz, Qazvin, and Herat or the cities of Khorasan.[5]

In Istanbul’s libraries, there are many manuscript Qur’ans with a similar style of illumination and with bindings having the same or similar composition to AKM386. Numerous examples were endowed to mosques and tombs founded by the sultan, members of the imperial family, or statesmen. Kept in chests or cupboards until the early years of the 20th century, they were then moved to libraries and museums, where they could be preserved under better conditions. Illuminated manuscript Qur’ans were foremost among the objects presented as diplomatic gifts to the Ottoman sultans, and consequently some Qur’ans of this kind were also sent as gifts by Safavid rulers to the Ottoman palace.

Between the mid to late 16th century, large numbers of mosques were founded in Istanbul by the sultans, their wives, mothers, daughters, sons, grand vezirs and other statesmen. The high demand for endowing these mosques with illuminated Qur’ans (which could be read and could serve as status symbols) meant that Istanbul artists found it difficult to produce sufficient quantities. Most likely, they ordered illuminated Qur’ans similar to AKM386 from Safavid Iran. Indeed, the large numbers of illuminated Qur’ans in Istanbul libraries demonstrates there was a rise in illuminated Qur’an production in Iranian cities other than Shiraz, and that these were sent to Istanbul.

The earliest examples of Islamic bindings were made with camel or goat skin. In some rare cases, craftsmen covered bindings with gold or silver plaques set with precious stones, ivory, or fabric. Leather bindings were decorated with stamped and tooled geometric and floriate motifs, which were usually gilded. Leather filigree was another type of decoration used for both covers and doublures. As attaching the binding to the body of a book at the spine was the final stage in the binding process, the binding could easily be separated from the book without causing any damage to the manuscript itself.

Until the early 20th century illuminated manuscript Qur’ans endowed to sacred buildings that were open to the public such as mosques and tombs were kept in cupboards or chests. Unfortunately this made them vulnerable to theft, and many were stolen. In some cases the entire book was taken, but frequently the binding was removed, leaving the textblock behind, or occasionally the textblock alone was taken. This explains why so many collections today contain bindings lacking their textblocks.[6]

— Zeren Tanındı

Notes

[1] In my view the textblock belonging to AKM386 is a Qur’an in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul (T.417, 50 x 37 cm). This Qur’an was copied by Muhammed b. Şemseddin b. Muhammed b. Emir Ali on 7 Rebiyülevvel 970 (4 November 1562). Fols.1v-2r and 2v-3r are elaborately illuminated. The Qur’an was endowed by grand vezir Sokullu Mehmed Paşa (d. 1579) to the mosque that he founded in the Galata district of Istanbul (Azapkapı Sokullu Cami). The Qur’an was taken from this mosque and placed in the museum in 1920. There is another Qur’an in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art with similar illumination that also belonged to Sokullu Mehmed Paşa and came from the same mosque. It is not dated but the name of the calligrapher is Ali b. Muhammed. Like T.417, the original binding of this Qur’an is missing (Acc. no. T.418, 49 x 35 cm).

[2] See Marchal, cat. 305.

[3] Inscriptions in the 11 cartouches, read from right to left, starting at the top:

1. The Prophet, may greetings be upon Him, spoke thus:

2. Whosoever reads a surah from the Koran and thinks it is ... [? missing line]

3. God’s emissary spoke thus

4. The most auspicious among you are they who learn and teach the Koran

5. The most meritorious form of worship is reading the Qur’an

6. The most auspicious among you are they who read the Qur’an and cause it to be recited

7. God forgives those who persevere in an undertaking

8. And [the Prophet] declared: He who knows the Koran … [? missing line]

9. The most meritorious form of worship is reading the Koran

10. The most auspicious act is ritual prayer; and then reading the Koran

11. and reading the verses of God

Explanation: The lines in cartouches 9, 10, and 11 form a single text that reads as follows: The most meritorious form of worship is reading the Qur’an; the most auspicious act is ritual prayer; and then reading the Qur’an and reading the verses of God.

[4] On bindings with the same stylistic features that have survived without their textblocks, see Déroche and Gladiss, 69, 72–3.

[5] Rebhan and Riesterer, cat.19; Tanındı 2003, 178–81; Tanındı 2010, 105–6, Farhad and Rettig, 272–91.

[6] Bosch, Carswell, and Petherbridge, 85–215.

References

Bosch, Gulnar, John Carswell and Guy Petherbridge. Islamic Bindings and Bookmaking. Chicago: Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, 1981. ISBN: 9780918986313

Déroche, François and Almut von Gladiss. Buchkunst zur Ehre Allahs. Der Prachtkoran im Museum für Islamische Kunst. Berlin: Museum für Islamische Kunst, 1999. ISBN: 9783886092765

Farhad, Massumeh and Simon Rettig. The Art of the Qur’an. Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts. Washington, DC: Arthur M Sackler Gallery and Smithsonian Institution, 2016. ISBN: 9781588345783

Marchal, Henri. Arts de I’Islam, Des origines à 1700, dans les collections publiques françaises, Orangerie des Tuileries 22 juin–30 août 1971. Paris: Réunion des musées nationauz, 1971.

Rebhan, Helga and Winfried Riesterer. Prachtcorane aus tausend Jahren. Handschriften aus dem Bestand der Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. München: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 1998. ISBN: 9783447041164

Tanındı, Zeren. “Safavid Bookbinding,” Hunt for Paradise. Court Arts of Safavid Iran 1501–1576, eds. Jon Thompson and Sheila R.Canby, Skira, Milano, 2003, 155–184. ISBN: 9788884915900

---. “The Bindings and Illuminations of the Qur’an,” The 1400th Anniversary of the Qur’an. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art Qur’an Collection, Istanbul, 2010, 90–121. ISBN: 9789757843177

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.