Click on the image to zoom

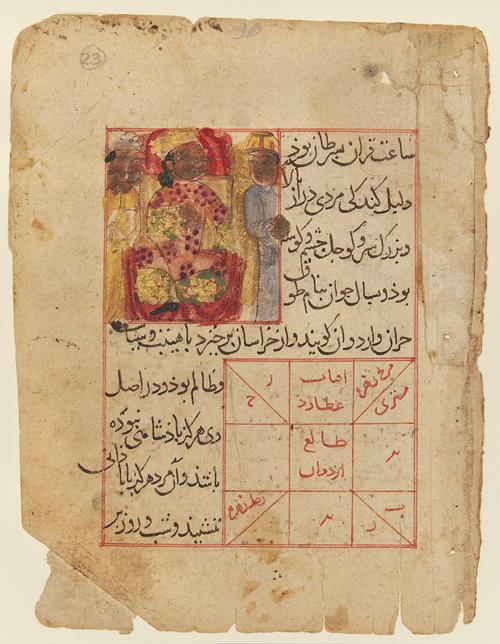

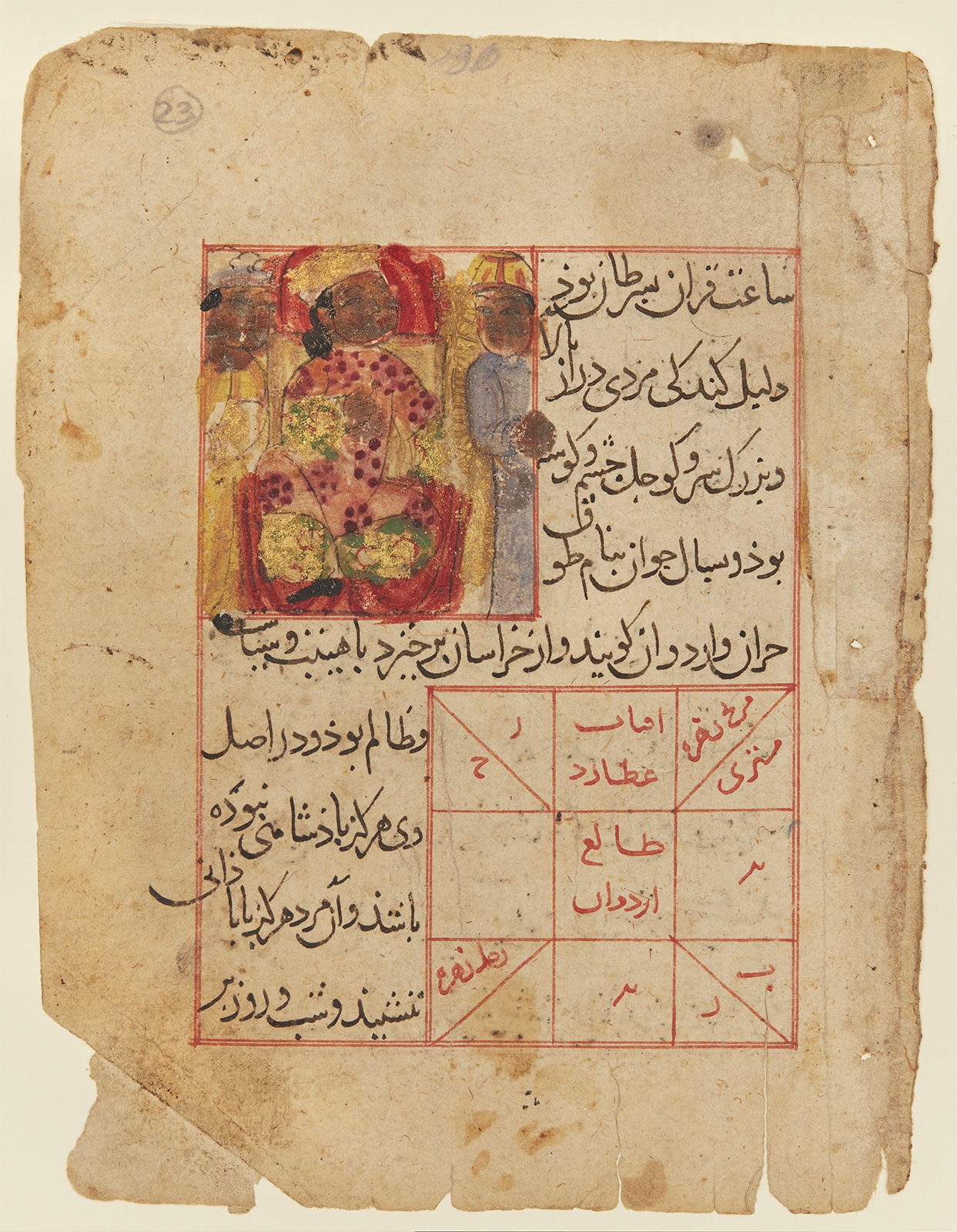

Horoscope of the tyrant Ardavan

- Accession Number:AKM86

- Place:Iran, Shiraz

- Dimensions:15.4 x 12 cm

- Date:early 14th Century

- Materials and Technique:Ink, watercolour, and gold pigment on paper

This folio, along with two others in the Aga Khan Museum Collection (AKM26 and AKM87), comes from the earliest and only illustrated manuscript of an untitled and anonymous Zoroastrian apocalyptic text written after the Mongol conquest of the Middle East.[1] In its entirety, the text draws on Islamic astral sciences; popular stories of prophets and kings; and Zoroastrianism, an ancient religion practised widely in Iran long before the arrival of Islam. This folio and folio AKM87, which follows it, tell of the fall of the Ashkanian/Arsacid dynasty and the rise of the Sasanians (224–651) through the horoscopes of various leaders. The text does not identify its subjects directly, but describes a period of political disruption when many individuals will seek the kingship, “even though it will not be granted to any but the seed of Sasan.”

Further Reading

The accompanying horoscope figures name the subjects of these folios (and presumably of the images found on them) as Ardavan and Kay Kavus. Ardavan is here to be identified as the last Arsacid ruler, though the name Kay Kavus is probably borrowed from the legendary Kayanian dynasty. In describing the appearance of Ardavan, folio 86 notes, “in his youth he will have the name Tauq of Harran, and they will call him that.” A character named Tauq, son of Harran, appears in various legends about the early Islamic period. In some, ʿAli takes the ring of Solomon from the body of Tauq b. Harran; in the Hamzahnama (Book of Hamza), he is a brigand who intimidates people with a tiger until the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle, Hamza b. ʿAbd al-Muttalib, converts him and takes him into his entourage.[2] Neither of these traditions fits cleanly with historical traditions surrounding the Ashkanian/Arsacid period, but both support the notion that Ardavan was an outlaw and tyrant.

Tauq b. Harran is just one of several figures from popular narrative traditions who appear in the larger text of the manuscript from which these folios are taken. Elsewhere, the prophet Moses is consistently called “Sorkh Shaban Ahudar” (roughly, the “Red Gazelle Herder”), while the ʿAbbasids are referred to as the descendants of “Hashim of the Leather Girdle.” These epithets are borrowed from Zoroastrian apocalyptic tradition. Hashim of the Leather Girdle is an Islamic-era reinterpretation of an early Zoroastrian apocalyptic figure named Xēšm (Wrath) of the Bloody Club, who led an army of “parted-hair demons with leather girdles.”[3] The appearance of figures from Zoroastrian tradition alongside Tauq b. Harran—not to mention use of the term “donkey-sitters” (dirazgush-neshinan), a Zoroastrian euphemism for “prophets”—suggests that numerous popular storytelling traditions have contributed to the text of this manuscript.

— Stefan Kamola

Notes

[1] The full text can be found in Paris BnF ms. Sup. persan 380 and, slightly abbreviated, in London BL ms. Add. 7714. The text of this folio can be found in the Paris manuscript, folios 29a-b. Additional folios from this manuscript are found in the Princeton University Library (mss. Garrett 91G and 92G), Harvard University Library (ms. Persian 26), the al-Sabah Collection (LNS MS. 50a-b), and the Royal Ontario Museum (980.115.7a-c). High resolution images of the Princeton folios from this collection (Princeton University Library ms. Garrett 91G and 92G), are available online: http://pudl.princeton.edu/objects/7d278w76c. High resolution images of the Harvard folio (ms. Persian 26) are available online: https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:10773911$1i.

[2] This understanding of stories surrounding Ṭauq, son of Ḥarran comes from personal communication with Dan Sheffield and from Pritchett, The Romance Tradition, 265.

[3] The conflation of the Avestan demon of wrath with the soldiers of the ʿAbbasid revolution was probably facilitated by the phonetic similarity between Hashim, the clan of the Prophet Muhammad, and Ḥashim “of the Leather Girdle.” For a discussion of Hashim of the Leather Girdle, see Cereti, The Zand ī Wahman Yasn, 13.

References

Adamova, A., and M. Bayani, Persian Painting: the Arts of the Book and Portraiture, London, 2015. ISBN: 9780500970676

Cereti, C.G., The Zand ī Wahman Yasn: a Zoroastrian Apocalypse, Rome 1995. ISBN: 9788863230888

Grube, E., Muslim Miniature Paintings from the XIII to XIX Century from Collections in the United States and Canada, Venice, 1962.

Kamola, S., “Lords of the Age: a Thirteenth-Century Zoroastrian Apocalypse from Fars” (forthcoming).

Nykl, A.R., “Ali ibn Abi Talib’s Horoscope,” Ars Islamica 10 (1943), 152–3.

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.