Click on the image to zoom

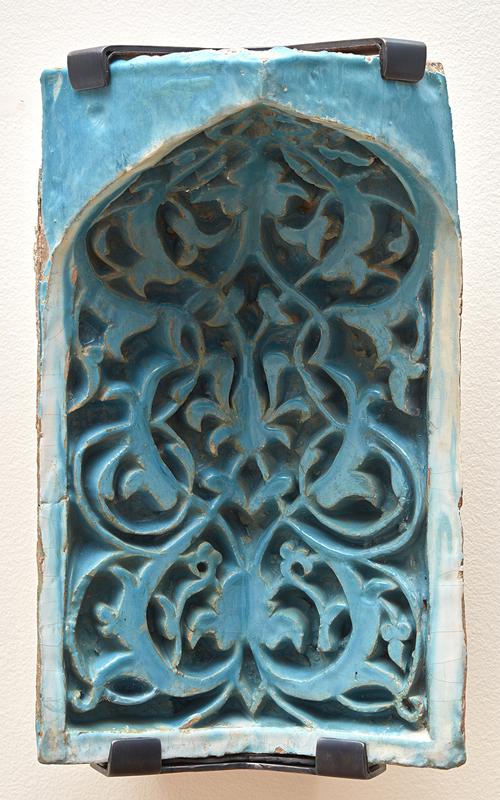

An Architectural element (Muqarnas)

- Accession Number:AKM574

- Place:Uzbekistan, Samarqand (possibly)

- Dimensions:30 cm × 18.5 cm

- Date:second half of 15th century

- Materials and Technique:Earthenware, carved, moulded and painted with opaque turquoise glaze

This architectural element from Central Asia showcases muqarnas ornamentation, a three-dimensional honeycomb-like decoration executed in a variety of media—including stucco, brick, wood, stone, and earthenware—across the Islamic world from the 12th century onwards.[1]

This elaborate example emphasizes the complexity of muqarnas ornamentation. Arranged around a vertical symmetrical axis and composed of twisted interlace with a lotus flower as its central design, it suggests the integration of Chinese decorative elements with the spiritual symbolism of Buddhism. The lotus flower had been part of the artistic repertoire of Iranian art and architecture since the 14th century, coinciding with the birth of the Mongol Empire. Some Mongol rulers, including Oljaitu, practised Buddhism.[2]

The underglaze paint in turquoise is a typical colour of architectural ornamentation during Timurid rule (1370–1507).[3] Timurid cities such as Shahr-i Sabz, Samarqand, Bukhara in today’s Uzbekistan, and Herat in Afghanistan became centres of art and culture as rulers (often forcibly) recruited artists and artisans from diverse regions of the empire to showcase the splendour and power of the Timurid dynasty.[4]

Notes

1. See Yasser Tabbaa, “Muqarnas,” Grove Art Online (2003): https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T060413

2. Oljaitu (r. 1304–16), the Ilkhanid Mongol ruler of Iran, practised Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam throughout his life.

3. Timur, the Turco-Mongol ruler, established the long-lived Timurid Empire (1370–1507), which spanned a wide geography, including today’s Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Caucasus (much of Central Asia), Iran, and part of Turkey, Syria, Mesopotamia, India and Pakistan.

4. See Sheila S. Blair and Jonathan M. Bloom, The art and architecture of Islam, 1250–1800 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995), 37.

References

Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum: Architecture in Islamic Arts. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2011. ISBN: 9786054348084

Blair, Sheila S., and Jonathan M. Bloom. The art and architecture of Islam, 1250–1800. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN:9780300058888

Tabbaa, Yasser. “Muqarnas,” Grove Art Online, 2003.

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.