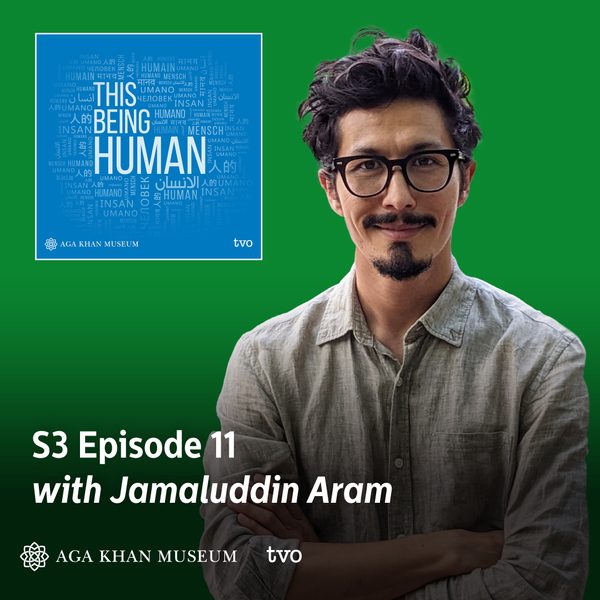

This Being Human - Jamaluddin Aram

Jamaluddin Aram is a documentary filmmaker, producer, and writer from Kabul, Afghanistan. He is the associate producer of the Academy Award-nominated film Buzkashi Boys, and his debut novel, Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on Wednesday was published in June, 2023. On this episode of This Being Human, Abdul-Rehman and Jamaluddin discuss how he fell in love with writing, the complexity of war stories, and his experience growing up in Afghanistan.

The Museum wishes to thank Nadir and Shabin Mohamed for their founding support of This Being Human, and The Hilary and Galen Weston Foundation for their generous support of This Being Human Season 3. This Being Human is proudly presented in partnership with TVO.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Welcome to This Being Human. I’m your host Abdul-Rehman Malik. On this podcast, I talk to extraordinary people from all over the world whose life, ideas and art are shaped by Muslim culture.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

My goal was to tell a story – to say, yes, there is war, but the war can limit at times how the everyday life is going, but it cannot stop it.

ADBUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Today, Afghan novelist Jamaluddin Aram.

The novel Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on Wednesday is set in a small town in Afghanistan in the early 1990s. The Soviet occupation has ended and a civil war is going on. While conflict and death lurks in the background, this is not a war novel. It’s a darkly hilarious series of stories about mundane human drama in a small town – interpersonal conflicts, rumours, business dilemmas and family expectations. The town is populated with rich, vivid characters – like a stubborn old shopkeeper who everyone calls The Mule; a crafty young girl who catches scorpions to sell their poison as a drug; and a teacher who lost his mind after reading an infamously difficult book. It’s beautifully written and deeply captivating work – so much so that it’s hard to believe it’s Jamaluddin Aram’s debut novel. Aram grew up near Kabul, but he’s currently living in Toronto which is where I reached him.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

I love the carpet behind you, Jamaluddin. It’s beautiful.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Yes. This is when we were younger, we used to make carpets exactly like this. Unfortunately, we were, you know, now that I think about it, I say I wish we could have kept one of them, you know, the things that we made. But it was because we were doing it for money. But this one is, you know, it’s woven by the same person who taught us how to make carpets. So that’s close, I think.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

That’s incredible. I just want to read to you the first line from the acknowledgments of Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on Wednesday. It really struck me when I read it, because it’s such a beautiful paragraph, but also incredibly emotive. And I had to dig in with you about it. “In my family”, you write, Jamaluddin, “everyone is a better storyteller than I am. I began to write to see if I could tell a story as good as theirs. But I know the competition is stiff and the road ahead is a long one. My father used to drive a truck and his anecdotes were laden with mechanical failures, epic weather calamities, bandits, swindlers and clowns. My mother was always surrounded by women who emptied out their hearts to her as if she was their therapist first and seamstress second.” I am just so taken by your description of your mother and your father. Tell me a little bit about the kinds of stories you were hearing and more than that, Jamaluddin, how did being with a mother and father like this sort of shape what story meant to you?

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Yeah, well I have been very fortunate to have been raised in a household with people who are… My mom and my dad, I think my father dropped out of school when he was grade 4 to help my grandfather. And my mom never went to school. The way they approached life and the kind of stories that or the kind of memory that they have because they couldn’t read, I assume. So everything is in their memory of how to listen and how to tell those stories. Or if you take it a step further, how to make sense of their life because they have lived very challenging lives, right? So how do you make sense of that is to tell yourself and retell yourself those stories or those events that happened to you. So that is the family part. But if you take Afghanistan in general, it’s a country that is brimming with stories and people. I was just writing this in an interview with a literary magazine about the oral tradition of storytelling. And I mentioned that in Afghanistan- here you say, “Let’s grab a coffee and chat” right? Or “Let’s call and chat.” But in Afghanistan, that phrase you say this way, you say, “Let’s grab tea and tell stories.” Right? [Speaking Farsi] Qesse is story. And so that is-

ADBUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Almost like, almost like narratives.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Yeah. Yeah.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

We use the same word in Urdu, qissa.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Yeah. Yeah. So let’s have tea and tell stories. And then that is everywhere. I remember because there was not any other form of entertainment. So people, people who are like men who are older than us, they would just gather somewhere outside and they would sit for hours into the night. And they will say these stories. And those stories were not following any linear path. It was not about one topic, but it was just people sitting there and telling each other stories of, you know, how things were or funny stories or jokes and… I don’t think we do that here or we don’t have time or we don’t have that kind of close knit communities to… of course, there were no cell phones at that time, so people were not on their cell phones. They would just sit and listen while somebody was telling a story. And so this is, you are in a family where your mother and father have been through a lot and they tell stories of how things were. And then you go outside and you see other people tell stories, right? And probably it’s that is not a special thing to me, probably every Afghan could be a writer, you know, and tell those stories. It’s only that I sit down and write it.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Is there a particular story that you remember from your home? Is there a particular tale that strikes you even today and makes you maybe laugh or cry or have to pause for a second. Something through, you know, the mists of time that continues to kind of… Yeah, kind of prick at you.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

There are a lot of those stories and some of them are so magical. We are a very superstitious society, right? For example, in the title of the book I mentioned Wednesday and on Wednesdays, it was widely believed that if you are traveling somewhere, you should not depart on a Wednesday, right? You either wait till Thursday or you leave on Tuesday. It’s bad omen if you leave on a Wednesday. And so my mom was saying that her uncle was working on the field. And one day she sees him walking towards a direction that he wouldn’t walk at that time of the day.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Mhmm.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

And he looks very pale as if something is controlling him. So other people had already noticed this. So they’re following him. And they see a snake, like a giant snake with its mouth open, and it’s pulling everything towards it, right? And like swallows birds, little birds, they’re just flying into the snake’s mouth. And this man is also going there to be swallowed by the snake. And somebody has a gun and shoots and kills the snake.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Wow.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

And then this man, my mom’s uncle, he just drops on the floor as if that whatever that was that was pulling him towards it, that source is gone.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Wow.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

So he just faints and falls on the floor. Now that I think about it, that’s not reality. That is like magic. You know, you only hear things in fairy tales like that. But I fully trust my mother with her stories and I have no doubt in my mind that that thing happened, that there was a snake that was swallowing everything in its path. And if it was not shot, he would have swallowed my mom’s uncle too.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

One of the things I experienced as I’ve been reading your book is that it’s very easy to read. You have the gift of the storyteller because there’s a breeziness to it. Yet you’re talking about very difficult things, difficult relationships, difficult moments. And also there’s the tinge of the absurd that runs throughout the book, which makes me constantly smile. And yet I feel a little bit guilty when I do because the book is set against the backdrop of a war. But none of the drama is focused on the war. It’s just human life. Jamaluddin, tell me what you were thinking as you crafted this amazing narrative.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Thank you. That means a lot to me. So the whole idea behind writing the book was that we often hear about the war. A lot has been written about the war in Afghanistan, the anatomy of it, who is fighting who and how it has changed the region, how it has impacted the world, 9/11 and all of that. But we rarely hear about the day-to-day life of people, right? So when there is a war, for example, it’s very unfortunate that there’s always a war. You look at when the war was going on in Syria or now in Ukraine. You look from the outside because of the screen and because of the way the narratives have been shaped, your immediate reaction is that there is no ordinary life going on in these cities at war. So my goal was to – because I lived through a civil war – to tell a story; to say, yes, there is war, but the war can limit at times how the everyday life is going, but it cannot stop it. And in this book, everything that this community of people, they just go about their everyday life because there’s no alternative to it. If you’re hungry, you can’t just sit and wait for the war to end, right? You have to eat. So people have to work. Get food. if you are sick and in pain, whether that is a wound or you have dislocated your shoulder, you’re not going to sit and wait for the war to end, you have to find a way to relieve this pain, right? And, of course, you know, the human heart craves for affection and love. And you cannot wait for the war to end so that you can fall in love, right? These simple human emotions and sentiments, they’re older, more ancient than any war. When the wars end, people will deal with the same things. They have to eat. They have to stay healthy. If they are sick, they have to seek help. They fall in love. They get their heart broken. At war or not, these things are happening. So what I did, or tried to do in this book, is to kind of shift the focus from the war into the everyday life.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Mhmm.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

And it’s a beautiful thing when people dedicate themselves to live as fully as possible where there is a bigger threat lingering around.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

There’s also the sense Jamaluddin of some of your characters being so present in their moment. There’s a scene towards the beginning of the book where gunfire breaks out and one of the protagonists, Aziz, is really worried not because of the gunfire, but because his mom has sent him out to borrow salt from his auntie. He’s afraid if he fails in this mission, his mom is going to beat him. And then there’s another character who, you know, as mayhem begins to ensue, doesn’t want to put down his tea. I feel a lot of resonance to that. You know, I feel like, you know, when things start going a little crazy in the house and I got tea or coffee in my hand, I’m like, “Oh, address craziness or put down coffee? Not sure.” But this character doesn’t want to put down his tea. It’s the only gunfire in the book, actually, I feel. And it’s treated as an inconvenience more than a shock. And these scenes are really funny as well. And I’m left wondering, how much of this is reflecting your own experiences?

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

That scene actually happened. And I was there.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Oh my goodness.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

I don’t know why I was there.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Okay.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

But I was there. I think I heard the gunshots. And then I just followed the sound where it was. And now that I think about it, I say, that’s very dangerous. You hear the gunshots, you run away. But at that time, when you are that young, everything is very intriguing. So that sound pulled me in and I was just going. And until I went where the fighting was happening. And why probably it stayed with me, that memory, was because I saw our neighbours. There was a family living right across from our house. And his oldest son was in the trench and firing a gun, right? So it was very like I had seen this person around for years. And then now I see him firing a gun, right? So it was probably that sense of familiarity took the danger out of the situation. So I’m not seeing a man firing a gun. I’m seeing my neighbour firing a gun. Those are two very different things, right?

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Mhmm.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

And I was not alone. There were other people, too. It’s… Humans and danger, we have a very interesting relationship.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Mhmm. Tell me about that, Jamaluddin.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Our mind doesn’t process danger as, “Oh, I will get hurt.” Right? It’s more intriguing. We are very curious beings. You hear a sound, and it could be the sound of gunshots or, you know, missiles and rockets fired. And your curiosity takes the better of you and you want to know. What was it? Where did it happen? I remember during the war and after the war and even unfortunately, five, six years ago, there would be an explosion and people would run on top of their rooftops to see where it was, you know. And that is something that has stayed. It’s part of our nature. And I don’t think it will go away. If you’re in situations like that, you realize how curious beings we are.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

There’s a character in the book, Malem, he’s the calligraphy teacher, and you write in the narrative that he reads an infamous book called The Mother of Books. And you write in the novel, “You either beat the book or the book beats you.” And in his case, the book beats him and everyone thinks he’s lost his mind. And he goes around saying the most blasphemous things. So my question that came to me was, Jamaluddin Aram, did you beat the books or did the books beat you? And when did you realize that you were in love with not just reading and stories, but that you were in love with writing and literature and that’s what you had to do?

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Well, that is a very, very good question. The first part, the story of Malem and the book that he read, that is actually a true story. A true story in the sense that that that book growing up, I kept hearing my parents, my father and his friends talk about this book, right? And it was called The Mother of Books. And I think it was a religious text that nobody- I didn’t see it then. I haven’t seen a copy of it. But it was very much alive in the stories that there is this book that exists that it’s very hard to read. And you should be of a certain knowledge of religion and of life to be able to attempt reading this book. Even then, the book is so powerful that you might lose your mind, right? And they were just telling about this one person who had read a lot of books. And he was an older man, too, and he read The Mother of Books and he lost his mind. So that was always an example like you shouldn’t even if you got the chance, you found the book, don’t open it, don’t read it, because there is a chance you might lose your mind. So that was- I kind of draw upon that memory in this book.

The second part of your question, when did I become interested in writing? For the longest time, growing up as a kid, I wanted to become an actor for film and I never thought of writing. Not until late. I think it was in 2004 that I wrote my first short story in Farsi. But then I wrote, I think, between 2004 and 2016, when I started thinking about writing seriously, I think I produced three short stories and a handful of free verse poetry. And then I left that kind of storytelling, went into film filmmaking, documentary filmmaking thinking it might open a door for me to get into acting. But anybody who is interested in acting, you tell the story, they say that’s a very, very long shot to go into documentary filmmaking to become an actor. And they’re right. I never became an actor because it didn’t open any doors. But I, you know, made two short documentary films. I worked on a number of projects. And one of the films that I worked on is called Buzkashi Boys. It was nominated for an Academy Award in 2012. But when I was at Union College, I think it was during my third year that I took a creative writing course and I was doing just the coursework, writing short stories. I was thinking of becoming a journalist and I have a friend who studied English literature. He studied English and history and became a journalist. He’s a beautiful writer. So I was kind of following his path to journalism. And then that creative writing course at Union I took and I said, oh, I really, really like writing. And that’s when I started dedicating more time to writing. The first chapter of this book, I wrote this in 2016 and it came out in Numéro Cinq magazine. So that was my first piece of work, written in English and published outside Afghanistan. And then after that, I started, you know, spending more time writing and thinking that this is something that I really like and I want to keep writing.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

What was it like learning to write in your second language?

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

I think now in retrospect, what I really liked I think it was above all, the challenge of writing. I write very, very slowly. So for me, composing every sentence is a process, no matter how short the sentence is. For me, it’s a process to try to get it right in the first place, to communicate what I want to communicate through that sentence. And then once that is done, now I go back how to make that sentence sound better. You know? So if I wrote in Farsi, I probably wouldn’t have that kind of challenge because that language is in me. It’s in my blood, right? I probably would have breezed through it. But with English, there are so many different layers to peel to get to saying something – say it accurately, precisely and beautifully. And that is something that I finished this book and I’m working on a new project and I’m very, very happy that that challenge has not lost its freshness. It’s as fresh as it was when I first started writing in English.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

I love that. I love the way you embrace the difficulty of the craft. There’s something so remarkable about that process. It’s the hard work of it. It’s the craft of it. And yet as a reader, It’s the way that I effortlessly move through the prose that I think is a sign of how much you’ve worked on it.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Thank you very much. It makes me very glad to hear that. I think it was Hemingway when he wrote The Old Man and the Sea, and he mentioned somewhere that he worked his whole life to arrive or achieve a simplicity of language and prose with which to write The Old Man and the Sea.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Mhmm.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

And I think anything that you read and it reads easily, but there is some depth and substance to it – both in terms of the musicality of the language and also what the words are conveying in terms of themes and meaning – it means that whoever wrote it, they spent a lot of time making it in a way that it reads easily. But there’s a lot of hard work went into it to make it seamless, right? And so it’s a very big compliment to hear that from you. I appreciate it.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

It really does come from, from an experience with your words. Do you still dream? Do you still dream in Farsi?

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

I do. And I hope it doesn’t change.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Mhmm.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

I’ve left Afghanistan in 2013. I’ve been back a few times, but every time I dream, 95 or even more percent of those dreams take place in Afghanistan, in Kabul, in the neighbourhood that I grew up as a child. And they all are in Farsi.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Wow.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

And I sometimes think that I would never be able to dream of any other place or go into other places in my dreams, because every time I close my eyes, I’m back in Afghanistan.

ADBUL-REHMAN MALIK:

It also kind of begs the question for me about translation, not just translation of language, but translation of experience and memory. And, you know, this alchemy that a writer does by taking the things that are so deeply personal, that interior space, the insight, so to speak, that interior gaze that a writer has and then bring those stories forth. But there’s two moments in the book which really caught me. In one moment in the book, you show us a piece of calligraphy that one of the characters has penned. It’s beautiful, the calligraphy. And then there’s a place further on where there’s a page from an ancient text that is referred to and you actually printed. But neither of them are translated. And I thought that was a beautiful, that was a beautiful sort of moment of, I would say, Jamaluddin, of confidence. Can you tell us something about those untranslated pages in your book?

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

There were two reasons that I did that. One reason was that Seema, one of the characters in the book, she’s doing calligraphy. Calligraphy is a form of art that needs to be seen. You cannot talk about it. You have to see to be able to appreciate that art and that craft. So that was one reason. The other reason is that I wanted to, in a way, acknowledge and pay tribute to Afghan artists that are doing a wonderful job. And I really appreciate their art. One of them is Ibrahim Amini. He’s a poet from Afghanistan. And that page that you just mentioned, that is two lines from one of his poems that I really like. I’ve been reading Amini’s poetry for a very long time, So I wanted to include his poem in this book to pay tribute to him. And the person who did the calligraphy. He’s a master calligrapher from Afghanistan, Ali Baba Awrang, which I also thank him. So that is that part. And also that page, later on in the book that is from Hafez’s collection. I admire and really like reading Hafez. So it’s in a way, me, including people and texts that means something to me in the book. The other thing is that as much as I wrote this book for people who are not from Afghanistan because this is in English, but there are in a way, I put things in the book that only an Afghan can read, and they say, oh, I know that. There are phrases in the book that I put, and I don’t translate those phrases either. The reader I hope that they have the patience to read and kind of grasp the meaning from the context, because I’m not, you know, translating every phrase. And those are those small little details that I put so that an Afghan, when they read, they hear that Persian, Farsi term or phrase in their head and they say, oh yeah, that is how we talk. You know?

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

I get that. Jamaluddin, as we start to as we start to wrap up, you approach both your work and life with a kind of a calm generosity, which I really appreciate and really, really feel. You know, I’m always interested in this kind of – and you mentioned it before – about the place the writer occupies between the natural and the supernatural. And I think so much of the poetry of the places that we come from, of the poetry of Afghanistan and of Rumi, they are words that are imbued with spirit. And I wonder how you as a writer, navigate that world, the spiritual world.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

You mentioned Rumi. And in one of Rumi’s poem, he says, [speaking Farsi] is the nowhere. If I can attempt to translate that line of Rumi.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Please, please.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

He says, “You are the king of nowhere. Don’t isolate and limit yourself to a place.” Right? And I think the world of the spirituality, the spiritual world. First and foremost, I think it is, we are seeking something that we will never find but in the process of the search, we are finding a place where we belong. And in Afghanistan, you can see people are reading poetry, people are telling stories to each other, people are gossiping and spreading rumors. And all of that is a search for the truth, right? And some people just go to the mosque to pray and some people go to the mosque to steal. All of these things, we are very restless and we are searching for something. And I think the more we are open to the search, the better off we are as individuals and also as societies in general.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Jamaluddin, tell me about a recent joy or a recent meanness that came to you as an unexpected visitor.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

This visitor is a new awareness for me. And I’ve been thinking more consciously about it. And in the past couple of days in particular. That we are individuals, but we are also living in a society in a time where everybody is thinking about themselves, right? The new awareness that I have is if we can take a moment each day or if that’s too overwhelming, take a moment each week and ask yourself the question, what have I done something for other people? What have I done something for the place, the community where I live? What have I done something for the animals that live around us, be it birds or dogs or cats? What have I done something not for myself, but for other people, right? And if we do that, I think the world that we are living in will be a much, much better place.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Your book has all kinds of beautiful little things that you truly make amazing. It’s been such a pleasure and a privilege to be able to spend this time with you. Thank you so much for being on This Being Human.

JAMALUDDIN ARAM:

Same here. Thank you for having me.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Jamaluddin Aram’s new book is called Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on Wednesday. My recommendation: go buy it now.

This Being Human is produced by Antica Productions in partnership with TVO. Our senior producer is Kevin Sexton. Our associate producer is Hailey Choi. Our executive producer is Laura Regehr. Stuart Coxe is the president of Antica Productions.

Mixing and sound design by Phil Wilson. Our associate audio editor is Cameron McIver. Original music by Boombox Sound.

Shaghayegh Tajvidi is TVO’s Managing Editor of Digital Video and Podcasts. Laurie Few is the executive for digital at TVO.

This Being Human is generously supported by the Aga Khan Museum. Through the arts, the Aga Khan Museum sparks wonder, curiosity, and understanding of Muslim cultures and their connection with other cultures.

The Museum wishes to thank The Hilary and Galen Weston Foundation for their generous support of This Being Human.