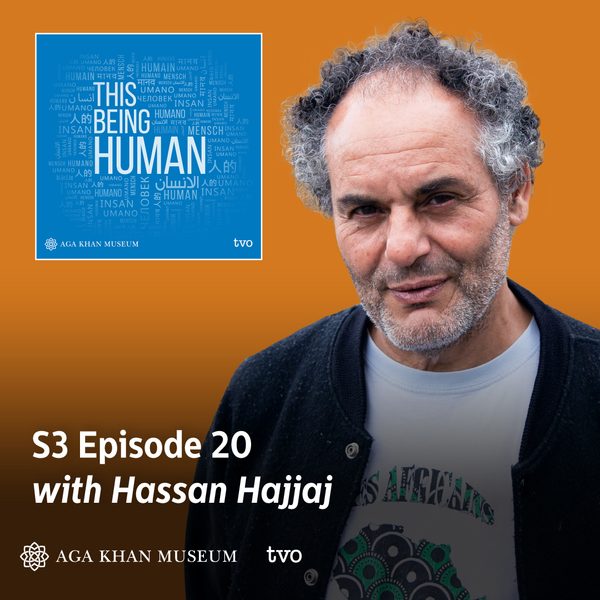

This Being Human - Hassan Hajjaj

Photographer Hassan Hajjaj has an iconic style that blends elements of pop art, hip hop culture and North African fashion. It spans series like Kesh Angels, which depicts biker women in Marrakesh, as well as celebrity photoshoots and album art. His works have been featured in renowned collections such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Institute of Islamic Cultures in Paris, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. This week, he joins Abdul-Rehman to talk about developing his unique style, his initial reluctance to call himself an artist, and how he’s seen the photography world change for the next generation.

The Museum wishes to thank Nadir and Shabin Mohamed for their founding support of This Being Human, and The Hilary and Galen Weston Foundation for their generous support of This Being Human Season 3. This Being Human is proudly presented in partnership with TVO.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Welcome to This Being Human. I’m your host Abdul-Rehman Malik. On this podcast, I talk to extraordinary people from all over the world whose life, ideas and art are shaped by Muslim culture.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

what I have seen for the last, I would say 15 years, there’s definitely a different mood of so many artists coming up from the continent Africa, Caribbean, South America, African American. I think now this younger generation have woken up to their culture. They seen the value what they’re coming from, what they didn’t value before.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Once you’ve seen Hassan Hajjaj’s photography, there’s no mistaking it. For the rest of your life, you will definitely know when you’re looking at one of his pieces. Subjects are dressed in explosive colors, inspired by traditional North African fashion, but with a decidedly modern flare. Their poses are reminiscent of hip hop album art. The background might be a street scene in Morocco or a colourful straw rug. Either way, the edges of the photo are lined with images of everyday products – cans of harissa paste or soda pop – repeated in a pop art style. One of his most famous series, Kesh Angels, depicts biker women in Morocco. He has also done iconic magazine shoots, including a Vogue cover shoot with popstar Billie Eilish and album covers for creatives like Riz Ahmed. Even as Hassan has become a major figure in African photography, he sits between many cultures, having been raised between London and Marrakech. His work has inspired a younger generation of artists, and has inevitably created imitators. No doubt, that’s the best form of flattery. I got Hassan Hajjaj on the phone when he was at his shop in London, so you’ll hear some of the hustle-bustle of a busy day in the background.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

You know, Hassan, you recently told GQ that for a long time you didn’t think of yourself as an artist. And I find that so hard to believe almost, because everything about your work cries out art and creativity. What was it that prevented you from thinking about yourself as an artist?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

I think that happened in the beginning of my career, you know, when I started, you know, I never studied art.I had lots of friends of mine who were artists around me that actually studied art. And, you know, that’s what they were trying to do for a living. And the passion of just taking pictures, this was sort of I just, you know, felt something within myself about photography. So I took pictures for many years without showing the work to anybody. I didn’t think of it being art, anything like that. And I think when I started showing the first body of work called Graphics from the Souk, in that body of work, I wanted to share it with my friends that I grew up with in London that were from different cultures, because in the 80s, you know, when you say something to your friend where you’re from, say, Jamaica, you say Bob Marley, rice and peas and it’s like Brazil, Samba, Pele on and on and on. When he got to me, said Morocco, it was like hashish, the Sahara, camel, dates, tajine and that kind of stuff. So it’s very caricature. So I wanted to do this body of work, called Graphics from the Souk, which is all about Arabic products with a kind of salon kind of, you know, space that you can sit in, listen to the music, really get that kind of 100% cultural thing in the contemporary way. So when I did this, I really didn’t think of it as being art. And then as I started showing it in galleries, the first few times, they would introduce me as their artist to their collectors or press. And I always in turn saying to the person that I’m not an artist. And the reason because of this is because I wasn’t too sure where it was going, what I had inside me, so I didn’t want to say that word until I knew I could prove it to myself to be able to carry that name. And that took about probably a couple of years before I got comfortable of saying, you know, this is what I’m doing, an artist. So I really was, you know, it’s sort of a journey for it to to get that name, now I think the best part and the favorite part is when you have occupation and you sign “artist,” that was the moment.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK

[laughing] When did you start taking photographs? Is it something that you started as a young person in your teens or in your childhood?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Yeah, probably like mid-80s. You know, just camera, take pictures of friends and, you know, it wasn’t really sure what I was doing to be honest with you. But also I was a big magazine and, and I loved photography. I think that was my schooling, just looking at magazines and books and stuff like that. And without realizing you’re studying, you know, about images and stuff like that. And at the same time, I’m not really a technical photographer, I’m more about an image, you know. I’ve got taught by a friend that he’s always using film. I just learned to use it in a basic way, but for me it was always about the image and what can the image say. So really it was a journey and I think with the photography, I probably started in the 80s, used Polaroid, used film. And then I think mid-90s I was shooting so much until I met the curator Rose Isa, who was very important in my career, because she was a big [?] for Arab artists. So I knew her and I said if you could look at my work to see what she thinks or if I had anything in there. And I remember walking to a house with a plastic bag full of negs and, you know, contact sheets. And she looks at them. She goes, “Well, Hassan, you have about five years worth of shows here.” She goes, If you want, you can stop. We can do shows. You know, “we”? You know, that was like a moment that she wanted to work, yeah, help me out and work with me to release me to the art world. And that was a good thing she said to me, because once I came out of her house, for a while if she said we got five years worth of work, let me go and you know, really work and try to have like ten-15 years worth of, of shows. And that’s what I did. Ya know, I just went, because I had that passion at that time and stuff like that. And sometimes when you have this, you have to follow it while it’s hot as they say.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK

You know, I love seeing the world through your eyes. That’s what I love it.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Thank you.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK

And it’s so distinctive. And I have to ask, did you kind of grow up in a creative family? I’m like what did your parents and those around you think of your passion?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Not at all. You know, my parents actually come from a village. You know, they came from, they couldn’t even read or write. They’re very [?], you know? So [?] and the English. So there was nothing to do with artistic. But at the same time growing up in Morocco in my early stage, there was things that you have to create for, you know, in season you might do flying kites that you have to make yourself. You might pick up shells on the beach and then we have an army barracks. We either used to practice and get like dead bullets and make them into necklaces. You know, we had like games, summer games, using tops of bottles, you know, things like that. So without realizing, that was there, but not thinking as creative, just something that was happening. You know, usage and something that as a kid you might do. And I think, you know, when I was a teenager, then I had mainly creative people around me. From everything, from music, deejays, designers, photographers and on and on. And this was really my school in a sense, to have these people around me as well.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Because of this creative environment, it made perfect sense to just try stuff out and incorporate everything around him, even if he didn’t have any plans about where it was going.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

I was an assistant stylist for fashion, like catwalk shows and a couple of magazines. A friend of mine was doing music videos, so I worked behind the scenes doing all sorts of stuff. I was running underground parties, putting deejays on, dressing up the space, it was illegal. You know, trying to kind of design my own way for the brand. So this was like my university. So when I started in the pictures, this came into my photographs without realizing it, it just seemed natural, I was like, oh, yeah, I have an idea. I’m going to go and dress up five girls with this. I’ll go and buy the textile and, you know, have it made, and take the picture and then frame it.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

If you don’t work in the art world, there’s a good chance you don’t think a lot about the frame that a picture sits in. But the frame is a huge part of what makes Hassan’s style so recognizable. His pictures are surrounded by images of food products – Coke and Fanta cans, or cans of tomatoes, or tins of spam — repeated in patterns that make them look beautiful.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

That really came from my early work. My early work Graphics from the Souk was all about Arabic products, that I shot and then played with Photoshop. And then I actually printed them on canvas. They look like between the photograph and painting. But I also had a setting called Le Salon, I was using Coca-Cola crates, road signs. So it was literally like a street language in that kind of way, but still giving it that kind of North African, Arabic, whatever you want to call it, style. As I was doing this, also I was coming from a culture that we grew up on counterfeit. And without realizing, this also came into my work. So it wasn’t something I went up my way. It was just like, okay, I know if I’ve got a woman with the Louis Vuitton veil would get looked at differently than having a black veil. How will that be read? So these points were already embedded in me and just came out naturally. And as I started showing my photography, I wanted to bridge my early work called Graphic from the Souk into the photography. And instead of having it printed on canvas, I wanted to actually use the products around the frame. So I thought this will definitely give it a contemporary look. Also, I didn’t want just to have the [?] in the frame to be part of the artwork. And the reason of this also, when I looked at the museums and you look at these beautiful paintings from, you know, centuries ago, you see them, they always had this gold frame that was made for that painting and they still have the same painting now. So that’s part of the painting. I don’t think somebody buys it, going to take the frame and put another frame. That comes with it.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

There’s also a sort of universal language to those products. A Coke can is recognizable around the world, even if the text on it is in Arabic.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

And sadly enough, sometimes people see the product before they see the picture, you know? I’ve had it so many times, hey look Coca-Cola or Louis Vuitton. So with all this, I found I have a strength in the work that it can communicate to a kid, black or white, old, young. It didn’t have any barriers. And for me that was important. As somebody coming from not being from the art world and somebody who was scared to go to a gallery I hate going to the museum, to have people like myself hopefully see something in life, something about the work, even if not if they have a debate, it’s even good. So that was really the process. And I think with all that it became like a style, like you said.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

I love it. I love the idea how you turn to like these sort of ersatz fashion and downmarket items, and you make them into something that’s high fashion, something that is…

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Yeah.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

…super edgy, contemporary and alive. But I have to ask you about one thing. At your recent exhibition in New York, you featured these three models wearing these floral jalabiyas, these row beautiful robes, but they seemed to be made out of those velour blankets that I see aunties and uncles carrying home from their trips to Dubai. In fact, in our family, they’re called like Dubai blankets. And I was like I was like, Hassan’s messing with me, man. Hassan’s messing with me. Tell me about that, because I noticed it right away. I’m like, there’s the Dubai blankets! He’s turned the Dubai blankets into fashion.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

So basically, you know, when I lived by Camden block market. I have the shop up [?] Market. And I live in the Medina of Marrakesh in the market. So when I decided to kind of call myself the artist, what would you want me to do? And so I wanted to do something, making something out of nothing, as cheap as possible. Obviously, I didn’t have the money to make something grand. So the blanket is exactly that, what you said, it speaks volume because it gets used. We all have them in what’s so-called the Third World. Everywhere you have them. So for me, the beautiful, the patterns are quite sort of out there. And so I decided to make a whole range and shoot with them and make them also look in the picture that they could look like from an expensive brand in a sense.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK I love it. And it was such an ubiquitous item, but it’s kind of like, if you know, you know, isn’t it? And I think that’s the interesting thing about your work, Hassan, among the many interesting things is that your work explores identity, of course, globalization, but I actually feel, Hassan, that you’re taking us to the other side of those conversations. I mean, I almost feel like is this generation interested in a discussion of identity, because they’re already so comfortable being in four places at the same time, just like you are? I wonder how these questions of identity fit into your work now.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Well, I think you said it all. I think it was definitely what’s around me, and that’s what I grew up with. And also since I always attempt, trying to present another side of people that don’t get looked into, that will understand it. That’s more important to me than having a big curator going, wow this is nice. Whatever. Because this is about the people, you know, my pictures are about people. It’s about the type of people, you know, the sometimes do not have it. Sometimes you know, the ones that strive and sometimes they have something unique about them, but are not mainstream. So this is really like you said, you understood it. And maybe you’re gonna be one of out 1000 that understood the blankets. And for me that’s great because it means I can communicate with you. We are on the same, you know, let’s say wavelength in this sense.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

I mean, as an artist, I guess you’re always speaking and communicating. And it’s, in a way, it’s like this is it, right? The photography, these beautiful images, are the medium through which we’re having a conversation. And I think there’s so many, there’s so many fascinating conversations that you invite us into through your photography, and of course, we can’t but talk about Kesh Angels, which featured these incredible women bikers. It’s among your most iconic work. And it’s among the images that people reference when they speak about you. I’ve always wondered who are the Kesh Angels? Tell us about the process of producing this series of of now iconic photographs.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

So Kesh Angels I started shooting in the 90s. Kesh Angels is short for Marrakech Angels. Again, playing with the big brands and big names, I took, what do you call it, um, The Hells Angels.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK

The Hell’s Angels, right.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

So I put Kesh Angels. And basically ya know, in, I lived in Marrakesh, and everybody uses scooters, bikes, you know, motorbikes because of the Medina, the layout of the city. I have one myself. And everybody uses them. Like young, old, you know, traditional, contemporary. So really, I just sort of found it fascinating, all these women with their veils, driving the bikes, because I knew in that in Europe they always say this is a uncomfort or it’s unreal. So really, studied the body language, how they would sit on them, how they would ride them and stuff like that. And now we kind of stage them with some of my outfits and sometimes their outfits and played on this, so as to kind of like a cinematic image. So it seemed to connect and it seemed made, you know, like ya know, some time I suppose an artist has a certain body of work that becomes more popular and then the rest of the rest of the work, and I think Kesh Angels definitely did this.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK

You know, you know, as you’re as you’re speaking, as I, I kind of think to myself. This is what sets you apart. Your subjects are as alive as your sets. Your sets are important and as alive as your subjects. When you’re conceptualizing a project, do you start with the subject and build from there, or do you kind of look at the context and say, I know I could see what might belong there?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

It’s definitely normally to do with the person most of the time. You know, it’s about, the only person. Because they were the ones that are going to bring it to the table at the end of the day. All the rest is me dressing them up and, you know, trying to make them stand out in a unique way. But normally it could be a person, that’s the most thing. But then some it could be textile. I could see something, I’m like, Oh God, if I buy this, I can design something for he or she or they. You know, so it comes, as I start to understand what I’m doing. As I said earlier in my conversation, it took me a while to question myself. What, what, what am I going to do? What am I going to do after my first solo show? What am I trying to say? And I guess it really is as real as possible to keep it around me in the markets. People that I’m with. And as you know, as the work gets popular, you start to meet new people that want to have pictures taken and stuff like that. But really, I would say it’s people because at the end of the day, I have to trust for them to be sitting in front of the camera and have that energy coming out of them.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK

I have a feeling that you are a consummate collector of cool, quirky, unusual and odd things. I imagine that in the back of your shop right now. Yes, exactly. We’re talking to you in your shop, that you have a secret vault of all kinds of unusual, weird, cool stuff, and you’re just waiting to use it, are you?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Yeah, I wish, I mean I wish I can show you. So you know, as I start off along my early part of art, I decided to really make design and collect stuff. So when somebody comes, I can through that vibe and pull out something that’s already and then sometimes, you know, like today I just there’s a kid I really want to shoot. His name’s [?], that’s doing amazing stuff here, different. And I’ve been dying to shoot him. And he came today, I had a meeting with him. So today I said, Look, you’re a painter. Here’s some outfits, go and paint on them. Here’s some backdrops, go and paint on them. We shoot on Saturday. So, you know, it’s like, it depends who it is. So, you know, sometimes I can make something for somebody specifically, but let’s say is like a painter. You have to have your oils, you know, in the studio at all times and your canvases. So obviously I have to have this bit for myself as well.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK

Hassan, you talked about being that young, you know the young photographer with the carrier bag of negatives and contact sheets walking into your, you know, into, into a curator’s home and saying, hey this is what I’ve been doing and being told that there’s some incredible work here. Fast forward to the Hassan Hajjaj who’s asked to do the photoshoot for Billie Eilish for Vogue and you see these images and you stage these images for the most iconic and important publications, you know, in fashion, in design, in art in the world. How do you make sense of that?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Well, you know, it’s sometimes like asking me this, I still sometimes think, did that really happen? I mean, before getting to people like Billie Eilish or, you know, these celebrities I shot, I have to say, you know, for them to approach me or their team was really, I suppose, the work I did. You know, all the people that been in my pictures, that gave that vibe for them to take notice and be, that want to be part of this. So with that, the people I shot, I don’t want the celebrities to overshadow all that 30 years worth of shoots. But, you know, it was a surprise call. And it was like so fast. It’s like, you know, we need to shoot next week, Saturday, and I had to come to London on Saturday morning from Dubai, pack up my stuff and then go back to the airport or Sunday evening or whatever day it was, and then try the same day, get there, and all the sudden you’ve got all this kind of things. I mean, you know, sort of I always say to myself, if anything like this happen, she’s a human. Don’ t look at her — You know, she’s already been probably having pictures taken by hundreds or thousands of photographers. So she’s really used to this. So just keep it real and just being, you know, as normal with her as like friends are I’ll shoot. So that was amazing. I mean, for me, that was good questioning why I was going to do it, why did I want to do it, and also it was good, like being, you know, to have somebody like Vogue and have the cover is good for somebody from my background to open up other doors. So I think of that in different ways. You know, and in the good way, that could happen. So it was a nice moment. Yeah, it’s very bizarre, but it was a nice moment.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

I love the moniker that some people give you, you know, the, the hip hop swagger photographer. And so it begs the question, what is the music that moves you? What’s up? What’s on Hassan’s playlist right now?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Wow. Well, today, today I’ve been listening to Orchestra Bell Bell and Dennis Brown and [?]. That’s today’s list.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

That is a perfect trifecta. Hassan, it is a perfect trifecta.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Bit of great grey in London, little bit of somber, so that was the mood today. To be honest with you, I think you know, it’s like, the older you get, your palate changes. It’s like in a lot of food, music, films and stuff like that, like when you have a bit more experiences and lots of things along the way, you know, in your life. And for me, really, I’ll listen to all types of music, you know, as long as it touches me, doesn’t matter if it’s Indian or whatever. But, you know, music was part of my photography in the sense even when I was using film, I would click my camera with the beat of the music without realizing.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Oh, I love that.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Yeah, Because now digital is different. Digital has a delay. But with the film, you know, I was always moving with the music, so I always, you know, I realized that I suppose most is I supposed to be caricature emotions? Most artists will have music when they paint or, you know, whatever I don’t want to be one does, but I definitely have that. And it’s something because, you know, I grew up lots of musicians around me. I sort of put on quite a lot live bands in the 80s, you know, I used to do parties for 11 years. So I went from like, you know, dubbed drum and bass, reggae, soul, funk, you know, all different eras, house garage, all that, you know, And then you listen at home, you know, jazz listening to, you know, grown up in Morocco, Arabic music and Egyptian music, so it’s hard to say. Just goes with the mood, it really does go with the mood, you know, And I like, I suppose, earthy music if it’s that meant to be.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

You know, as you speak about your work on there, there’s a real feeling and a sense of generosity. You’re someone who clearly cares. You care about the people that you’re working with, but also care about the collaborators and the makers and and the places that that, that you that you work in. And and you’ve become part of a kind of a kind of a remarkable global community of photographers who are challenging convention, who are sort of fast-forwarding beyond identity or shaping, I think a visual discourse. And the Tate Modern is running an incredible show currently of photographers from Africa, of which you are, of course, one of them also alongside, you know, incredible folks like Ida Holiday who we’ve had the honor of of of interviewing on this podcast. Which African artists or other photographers are exciting you these days? Who’s kind of feeding your soul out there in the field?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

I mean this is what I’m seeing and I can’t give the exact names, but what I have seen for the last, I would say 15 years, there’s definitely a different mood of so many artists coming up from the continent Africa, Caribbean, South America, African American. So there’s not just about Morocco, you know, there’s photography, there’s like, I don’t know what happened last 15 years, there’s so many great photographers, you know, I actually did a project called Mi Casa, Su Casa in 2016. And I decided shopping was to photographers Moroccan photographers, man and female. That became I’ll I’ll show that in the space that I had and I showed it in the museum, then New York. So there’s Ishamel. Zadie, for example, there’s Yoriyas, who’s like, you know, massive from Morocco. There’s reda [?] I’m doing his solo show for in Morocco for 154. I mean, there’s, you know, [names] I mean, there’s there’s so many, you know, and I think what’s happened, I think now this younger generation have woken up to their culture. they seen the value they’re coming from, what they didn’t value before. It’s sometimes it takes somebody from outside, like from the west to come and value something that might look very simple to them, that they live with by their [?] as a piece of art. So there’s like a bit of an awakening. And I think also it’s great because they have their own this new generation not working for a commercial gallery. They have these platforms, Instagram, you know, where they can share their work, they can get work from there. So it’s really exciting to see this, you know, because I’m coming from, you know, the other side of just, you know, showing in the gallery for a month, 200 people comes only 200 people seen your work. Now, if you show in the gallery, you know they can you can have 100 people come in and one click of a camera could be shared to 1000 or 100,000 people. So the games change and the younger kids as more self-sufficient because they have everything in front of them and sort of doing it themselves, like, you know [?} taking care. And this is going to be this is exciting. And, you know.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Do you see yourself as as the OG teacher now?

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Well, I’m just old school. I’m the old model. You know, I’m like I’m sort of film, partly digital, while they’re totally digital. Some are using film.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

You know? You know, we’re going back to analog. I collect vinyls now, you know, it’s we, we, thought we gave all that up. But, but there’s an art to that. There’s an art and there’s a, there’s an esthetic to that stuff that’s just that, that’s enduring and actually really powerful.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

You know, things change. You have to change with it and accept because if not, you’re going to be that old fart, as they say. And also it’s great to have young people around because I love working with them, because you learn from them, understand where they’re coming from, hopefully they can get something from you as well. And I always look at that way

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

Hassan, I wonder if you could tell me about a joy or a meanness that recently came to you as an unexpected visitor.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Now, just today, I think today was a funny day because this I said early on, I said it on this young kid called Sloan, who’s like, he’s a young painter, Nigerian. We spoke about doing a shoot a while back and we tried to happen make it this weekend. And he just happened to be in the neighborhood. And I just sent a message saying, Are we on for this weekend? He said, yes. I said, Listen, I have an idea. Can I give you some backdrop and some outfits? You can paint your paintings on them so I can have you with your paintings in it, like in your painting, in a sense. He said, Yeah. He goes, yeah, definitely. And I said, Well, listen, how can I get this stuff to you? He goes, well, where are you? I said I’m just in [?] Avenue, East London. He goes, I’m five minutes away, we’ll be there. So he came, we just vibed.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK:

May you always have continued success and may your work continue to inspire and animate the world in the way that only you can. It’s been such a pleasure having you on This being Human.

HASSAN HAJJAJ:

Thank you Abdul-Rehman. Thank you very much. Take care.

ABDUL-REHMAN MALIK VOICEOVER:

Thank you for listening to This Being Human. You can find links to Hassan Hajjaj’s work in the show notes. This Being Human is produced by Antica Productions in partnership with TVO. Our Senior Producer is Kevin Sexton. Our associate producer is Emily Morantz. Our executive producers are Laura Regehr and Stuart Coxe. Mixing and sound design by Phil Wilson. Our associate audio editor is Cameron McIver. Original music by Boombox Sound. Shaghayegh Tajvidi is TVO’s Managing Editor of Digital Video and Podcasts. Laurie Few is the executive for digital at TVO. This Being Human is generously supported by the Aga Khan Museum. Through the arts, the Aga Khan Museum sparks wonder, curiosity, and understanding of Muslim cultures and their connection with other cultures. The Museum wishes to thank The Hilary and Galen Weston Foundation for their generous support of This Being Human.