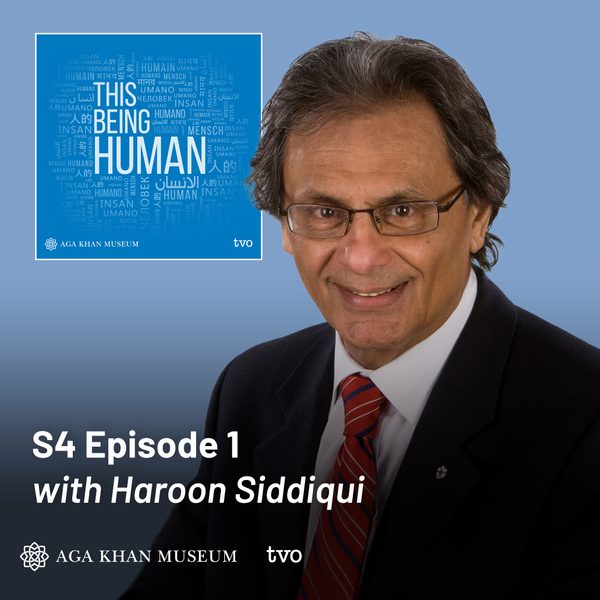

This Being Human - Haroon Siddiqui

The Museum wishes to thank Nadir and Shabin Mohamed for their founding support of This Being Human. This Being Human is proudly presented in partnership with TVO.

Show Notes

AR sits down with his long-time family-friend, author and former columnist for the Toronto Star, Haroon Siddiqui. They speak about Haroon’s love for Canada, how he got his start in journalism, and his latest book, My Name is Not Harry: A Memoir, a defiant and proud assertion of his Muslim identity in the face of Islamophobia.

Haroon Siddiqui: [00:41:51] where does this resiliency come from? It comes from this idea of the Charter of Rights and multiculturalism that all people are equal. That you deal with each other on an equal basis. So Canada has something unique. None of this is to say that Canada is not still racist. Racism is right just under the surface. [00:42:13][22.0]

Haroon Siddiqui: [00:42:38] But it is less so than elsewhere in the world.

*****

Haroon Siddiqui has had many titles. Reporter, columnist, editor, editorial page editor, editorial columnist and, most recently, editor emeritus. In fact, there are few roles in the newspaper business he hasn’t had.

To me he was always Uncle Haroon. My parents came to Canada a few years after Haroon Siddiqui did. They came to a country where they had no family – so we had to create a family. We had an entire ecosystem of Aunties and Uncles – no blood relations. They were like second parents to us Canadian born youngsters. Haroon was one the Uncles who most fascinated us. Erudite, worldly, incisive – I would look forward to speaking with him over chai and samosas at some community gathering.

Haroon Siddiqui immigrated to Canada, almost by accident, leaving behind a culturally rich life with deep family roots in his hometown of Hyderabad, India.

Since then he’s covered just about every major news story since he took his formative job at The Brandon Sun in 1968. He spent a decade traveling the country, soaking up – and reporting on – the unique experiences of each region.

Haroon’s career – and curiosity – also took him around the world, often into the heart of intense and world-shifting events including reporting from the frontline of the Iranian Revolution, making sense of post Cold War politics, and coming to terms with the aftermath of 9/11.

But his latest endeavor might have been his most difficult assignment yet. Haroon’s memoir titled “My Name is Not Harry” is a profound reflection on his career, Canadian values, his immigrant superpowers and the role he believes luck, or should I say divine destiny, has played in his incredible life.

I spoke to Haroon Siddiqui from his home in Toronto. I can’t think of a better way to launch Season 4 of This Being Human. And just so you know, I still call him Uncle Haroon.

****

AR Malik: I want to take us back into where our family histories connect. Because I grew up in a Muslim community in Toronto that I look back on now, having had experience of other Muslim communities, not only in Canada but in the United Kingdom, the United States, and frankly, around the world. And given that global experience, I look back on my upbringing, not only with a lot of fondness, but with a great deal of gratitude, because it was a remarkably diverse, intellectually diverse, spiritually diverse, ethnically diverse, racially diverse, linguistically diverse community. And in that community, there were people like you. I have an early memory of you that I want to share. We used to love family gatherings where you would where you would be there because you were one of, like, the most interesting uncles. And of course, we use uncle as a term of endearment, because most of us didn’t have family. We didn’t have our aunties and uncles and great grandparents. You were our aunties and uncles and grandparents. So I remember when you show up to a gathering, we’d be like, oh, that’s so cool. Uncle Haroon is here. We wanted to engage you because you were engaged in politics and, and the world, and you would read broadly and, and it was always something interesting to talk about with you. But we all realized that if we couldn’t make our point to you in 30 seconds or less, or capture your attention in 30s or less, we’d lost the moment. Even that you were ever the journalist. (laughs)

Haroon Siddiqui: Right. People take too long to make that a point. That’s a lesson in life. Yes. And now, as I’m getting old, I’m finding that I’m running into more and more people who like listening to their own voice. I don’t have to say anything. Just keep talking. Say ahhhh Yes! All right. Yes. Go ahead. Half an hour goes by so I don’t have to do anything anymore.

AR Malik: How did you look at us as young people growing up in Canada, as Canadians in kind of juxtaposition to your own experience of having come to Canada?

Haroon Siddiqui: Your age group and so on came smack in the middle of the 1980s, 1990s, when Canada was evolving every day. It was coming from a presumed white Christian nation. It was evolving into a multicultural nation.

AR Malik: Your book, “My Name is Not Harry” and we’re going to talk about the title in just a moment. Yeah. Has been called by some, readers and reviewers as a, as a love letter to Canada, and that’s I’ve been reading it, I too have been finding the book to be kind of this incredible kind of compendium of remarkable moments in your life. And underneath that there’s a lot of love for this country that you came to in 1967, as you describe, with maybe 100, maybe 200 dollars of foreign exchange in your pocket. Looking back on that time that you arrived, did you think this would be a country that you would fall in love with?

Haroon Siddiqui: No, you see, I mean, I came to Canada by accident. It was 1961 or 62, when I was working as a cub reporter at the Press Trust of India News Agency in what was then called Bombay, now Mumbai. Roland Michener, the High Commissioner of Canada, had come for a trade delegation. And in that reception he said something to the effect: a young man like you should go to Canada. And in my youthful impertinence I said, why would anyone want to go to Canada? It’s so bloody cold there, isn’t it? But he had planted a seed. Three years later, in 1965, I was back in Hyderabad, my hometown, and my friend said, immigration officer is coming from the Canadian Embassy. And I hadn’t made a reservation and no appointment. So I just phoned them and said, you know, are you willing to interview another guy? And he said, yeah, fine, come along. I went and at the end of it basically said, ‘you are in’. We simply proved that standards are very low at that time. But then I did not exercise that right for a year. And then it was running out. The Canadian Embassy was kind enough to send a reminder. Your days are running out. You know, you have to go. And I said, no, I can’t go. Can you give an extension? They gave an extension for a year. Then I came three days or four days before the next extension was coming to an end in 1967, and I came to Montreal. But the great thing that happened in Canada, as soon as I came, the enthusiasm dissipated very quickly because we could not find yogurt. There was no yogurt in Canada. How can you, how can you live without yogurt? (laughter)

Haroon Siddiqui: Being from India. So they had no basmati rice? No fruit, no vegetables that we eat, and so on. So instead of yogurt, we were given something called sour cream. And sour cream was a thick, bloody thing which sat, like, a blob in your tummy, you know. Anyway, I phoned my mother. And she said, in that case, better. You better come back home. What kind of place have you gone to that has no yogurt? So I’m glad I stayed. And now 50, 60 years out, Canada is the cuisine capital of the world. Every food is available here. That is a demographic transformation of this country.

AR Malik: The title of your memoir is actually quite arresting: My Name is Not Harry. And in all these decades that I’ve known you since I was a since I was a child, up until now, I had actually never heard this appellation, this name Harry applied to you. But clearly, it’s happened to you more than once. Do you have a clear memory of when someone first called you Harry?

Haroon Siddiqui: I think I had gone to Manitoba in 1968. And the premier of Manitoba in the late 70s was Sterling Lyon. And he used to call me Harry, and one day at the legislature, he said, hello, Harry. I said, Premier, I’ve told you my name is not Harry. I don’t look like Harry. I don’t want to be Harry. So there was an awkward silence and the moment passed. I was telling his story to a friend of mine Adrienne Clarkson, the former Governor-General. And she piped up as that is the title of your book! (laughter)

AR Malik Why were you in Manitoba, because we know from your history that the town that you went to, Brandon, has a population of about 30,000 people. And you came from this cultural, historic, civilizational hub of Hyderabad in India, which at that time, I think in a population of something like 1.5 million or more. I’m thinking about Haroon Siddiqui in Brandon, Manitoba. And I also wonder, were there some nights where you sat up in your bed and you said, ‘oh, did I make the wrong choice?’

Haroon Siddiqui: You see, when I come to Montreal and then I made my way to Toronto and of course, I had knocked on all the newspaper doors. Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, telegram. Everyone rejected me but Clark David. He was a legendary managing editor of the Globe and Mail. He said, no job for you. But I can send you to a place in Canada where you will get good training. And it’s a newspaper in Brandon, Manitoba. And I said, no, thank you. And I walked out. And eight months later, I could not find a job anywhere. And I have rejection letters from the smallest weeklies in Ontario. I phoned him back. I swallowed my pride, phoned him back. And true to his word, he said, no problem. I’ll phone them right away. And he phoned and he said, it’s an independent newspaper. And. And you will be well served by going there. So my first reaction to him was, why would anyone want to go to Brandon, Manitoba? It’s colder there than it is in Toronto. Anyway, I arrive there and it was a small independent newspaper. Editorially, it was very sound. It gave us all the opportunities that one could find anywhere. In the city of 35,000 people were very reserved. They didn’t warm up to you quickly. But once they did, they did. And then there is the ethos that is forged by extreme weather. That they come to each other’s aid. If you are ever stuck on that middle of a road or the side of a road in -30 weather, the very next car that’s going by will inevitably, invariably stop and help you out. Those are the kinds of people they are. So I had gone there for the explicit purpose of getting Canadian experience for the year, but I ended up staying for ten.

AR Malik: That’s an incredible amount of time.

Haroon Siddiqui: And actually, it’s a good thing because it gave a perspective of Canada from the prairies, which I would have never had, had I never left a big village called Toronto (Hmhm). In Toronto you can ghettoize yourself in various communities and so on. And I say that, not negatively, but there are many silos in like in any big city here that you’re forced to meet with everybody.

AR Malik: What was the most memorable story you covered in Brandon for the Brandon Sun?

Haroon Siddiqui: Oh there were many of them. The two things that stand out. When you went and covered elections and so on, all the catering was done by local volunteers. And if you were in a Ukrainian community, you got the best perogies. If you are in a Polish community, you got something special like that. So by the end of the election, you put on 4 or 5 pounds instead of losing pounds because you were so well fed and so on. And then one of those election rallies. In a community center, one little baby was staring at me and staring at me. And her mother got uncomfortable and she said, excuse me, sir, I apologize. He has never seen a brown person in his life. So I said, you don’t have to apologize. It’s something unique. Let him keep looking at me. You know, you learn something. So people are that isolated. Yet at the same time. There is that much honesty to them. That’s what I’m saying. There’s no malice in that, in that proposition.

AR Malik: And hearing that story. I think their curiosity matched yours.

Haroon Siddiqui: Yeah, if that kid has not seen anybody like me, he has not seen anybody. Like, that’s a fact of life you know.

STING/ SURVEY

AR Malik: I’m thinking back to when my father would describe you to me and I would say, what this Uncle Haroon reported and what is he known for? And he would tell me, well, you know, your Uncle Haroon was in Iran during the revolution. He reported back. His stories were syndicated all over the world. I want to take us back for a moment to that experience. Because in some ways, when I think about your career, and the story that you’ve written and lived so interesting is that there’s few journalists, I think, who could say they did everything. They did the cub reporting, they did the copy editing. You know, they probably got coffee for their editor, and they covered a revolution in Iran. And they became Canada editor for the Toronto Star. And they read the editorial page and they became a columnist. And you’ve done all those things.

Haroon Siddiqui: Yeah. You see, the first part of it is really a matter of luck, the kind of mentors you are lucky enough to have. Secondly, it coincided with a lucky period in journalism where money was no bar, money was flowing. Newspapers are making enormous profits of 25, 30% and so on. That enabled independent journalism.

So in those days, anything happened anywhere at a moment’s notice, they would say, go to the airport.

AR Malik: And by this time, you had arrived back from Manitoba and you’d been hired at the Toronto Star. That must have been a massive sort of cultural change from going from Brandon back to this kind of, you know, growing multicultural village of Toronto. Was that a little bit of a shock?

Haroon Siddiqui: Not really. Not really, you see India prepares you for everything.

AR Malik: I love that, I love that (laughs).

Haroon Siddiqui: People are street smart and so on. In India, the 3000 year old civilization. As a muslim, you have a 1500 year old great civilization of knowledge, theology, excellent science, medicine, this and that. So you’re not thrown off by anything. On your street lived Sikhs and Hindus and Muslims and the Russians and Christians and so on and so forth. And you respected each other. And I tell a story in this book, I think. My parents were a product of a madrasas.

AR Malik: Hmhm.

Haroon Siddiqui: Madrassas were great institutions of learning. Hindus used to study at madrasa. You know, my father was a product of militant. He had a beard. He was Orthodox Muslim.

AR Malik: Isn’t that fascinating? Your father had memorized the Koran. He was deeply steeped in tradition. Yet your teachers are from a totally different tradition.

Haroon Siddiqui: And when I was growing up and I had failed at pre medicine. Pre-Engineering, atomic physics. This dabbled in literature. And then finally, when wanting to go into journalism, I went to my advisor and said I would take admission in journalism. And my father’s first response was if it’s alright with TGV, it’s alright by me. You could not only imagine two more disparate individuals, you know, one a product of a madrassa. The other is a Brahmin from the south. But both these figures occupy high places in the pantheon of India. Parent and teacher, deferring to each other, respecting each other. So these are profoundly different people but profoundly respectful of each other. So in my books there were more secular. More small ‘L’ liberal than many of the so-called secularists and liberals in the West. As we found out after 9/11. There’s a profoundness to it.

AR Malik: There is. And as you’re as you’re speaking, Uncle Haroon, I, I’m reflecting. I’m reflecting on not only career, but me as a product of Canada but also a product of, of mentors and elders like yourself. And in a way you’re articulating so beautifully I think what we’ve all felt in our bodies, in our hearts and our minds, but often have not been able to articulate so well that we do have the superpower. We have this ability to navigate through difference through differences of languages, of cultures and religions, and do so with a fair amount of grace and skill. It’s something that I guess as I approach 50, I’m very aware of, I’m aware of doing. But you’re articulating the roots of it. You’re articulating kind of where it came from and, and I don’t think we do that enough. I don’t think we mine that cultural, spiritual, intellectual DNA. But you’ve done this in your book. Particularly, you know, the first few chapters where you speak about these formative experiences of your family. This I mean, the book is a love letter to Canada. But these first chapters are actually a love letter to Hyderabad and the milieu that produced you and your mother and your father and your family.

Haroon Siddiqui [00:38:36] The original title of the book was going to be “My India, My Canada.” So that sort of captures it, you know, you know, the universal values that were taught, you know, the Canada that the Charter of Rights has produced today. It’s like the ulama, the Islamic ulama.

AR Malik The global spiritual community.

Haroon Siddiqui Communities of the community, you know, what, what is different? Yeah. You have not seen no communes. Zachary. No. Ansar was a local troublemaker by the leader of who we have created unto nations and tribes. So you might know each other. Not hate each other, not let alone war on each other. What was the prophet’s famous last sermon on the hadj? He addressing people right in front of him from Mount RFI. It says all mankind. He doesn’t say, oh, you fellow Muslims. He says all mankind. That’s how he addresses them. And then what are the rules laid out? Some of the rules laid out are, in effect, the precursors of the various sections of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in Canada, you know, respect each other. If a slave among you is named your leader, obey him. If he is chosen leader, respect him. So all are equal. So your greatness lies in your piety and your behavior in your dealings with fellow human beings and so on. So these are universal principles, common to all religions and they are being encoded in Canada now. What is the biggest fault line of the West these days? It’s a color line. Canada is the only OECD country that has a national consensus on immigration. Translation: let the brown people come in because the only immigrants that come are brown people. There is tension lately because of housing crisis. And they said that not only are we taking too many students. Are we opening the floodgates? Can we manage? But it has not deteriorated into xenophobia yet. And where does this resiliency come from? It comes from this idea of the Charter of Rights and multiculturalism that all people are equal. That you deal with each other on an equal basis. So Canada has something unique. None of this is to say that Canada is not still racist. Racism is right just under the surface. Are there double standards? Yes. Is there hypocrisy? Yes. But it is less so than elsewhere in the world. That’s why I’m saying.

STING

AR Malik As a journalist, as an editor, as a columnist, you’ve covered these, these faultlines. You know, last year you were awarded the lifetime Achievement award from the Canadian Journalism Foundation, which recognized your commitment to diversity, journalistic integrity and social justice. But you know what I think about a lot, particularly at this moment where the world is now, is the work of, of the journalist, of the storyteller, of the reporter is and can be not just intense, but it’s heartbreaking work. It’s jumping into the wounds that are out there in the, in the world. It’s at times really, really desperate. And I’ve been thinking a lot about that. I’ve been thinking a lot about that as a teacher, where I currently am working with students, but also been thinking a lot about that because we’ve seen the burden that journalists and those who are reporting the world take on. How did you navigate the heartbreak and that desperation? What helps you navigate the heartbreak?

Haroon Siddiqui: You sort of, develop, layers of insulation to start with. You develop a thick skin. And you also learn to remain one removed as a journalist. That’s old style journalism. You are an observer. You are not an activist. And that’s a distinction that is more and more lost because people take pride in being activists, reporters, and so on, activist citizens. The added element that again, came from my background as it would come to others as well, is a kind of empathy for other human beings.

AR Malik: Do you feel that in your work that you’ve always been going against the grain? Many of us, you know, in our readings of the mainstream media, would look forward to reading your columns because we knew they were going to provide a critical alternative, different way of looking at things. I mean, did you always feel that you were, you were pushing against the tide or did sometimes the tide flow with you?

Haroon Siddiqui You tried to be honest. And in trying to be honest, if you have to take on the tide, you take on the tide. And that comes with the turf. You know, my father, when I told him I was going to be a journalist, he said two things I said because journalism was considered the lowest of the low professions in our time. Nobody wanted to be a journalist. If you failed at everything else, you became a journalist, you see. So my father said, you realize something. No one will give their daughter to you in marriage. The second part, he said, was. You know, it would be easy to be popular. It would be more difficult to be respected. Try for the latter. Well that’s a tradition in the family. That’s a tradition of all the minor islands in India has turned up to the Sultans of the day.

AR Malik: Right. The scholars in your lineage.

Haroon Siddiqui: So the streak of independence just sort of comes naturally, comes from the baggage that he brought from back home. So this is good baggage from home.

AR Malik: Uncle Haroon, you write on the world. You comment on the world, you help us understand the world. And you’ve written a number of different books which talk about Muslim history, experience, Islamophobia. We’ve heard you speak and comment on global affairs. And yet this book is really different. It’s very personal. It’s about family. It’s about the quiet moments. First of all, what inspired you to finally write this story? And then the second thing is. I don’t know, I’m going to offer a hypothesis that I think this was the most difficult book that you’ve ever written.

Haroon Siddiqui: The book did not start out like that. The book simply started out how Canada has changed for the better in the last 50 years that I’ve been here, kind of thing. And then, a former publisher of mine, she said, no, write about your history in India. And I said, why is that? And she said, because we are an immigrant country and we bring complicated stories to Canada. And that is what enriches our national narrative. It’s a very profound thing to have said. So I said, no, I was going to write about my family. That’s a separate book. And she said, no, not write it here. So that’s how that came. But when you write like this, you have to write cross-culturally that it should travel across cultures, across languages. And so that’s very difficult. The most difficult thing was to follow. As a journalist, you are trained to take the eye out of the equation. You never say I think so. You just sit and observe at a distance. To write about yourself is the most difficult thing. And then there’s a great writer called Ron Graham in Canada who said, write about yourself as though you’re reporting on somebody else. So I said, what does that mean? You will figure it out. So you will find your voice. So hopefully found the voice. Readers will decide that.

AR Malik: Were there moments of sheer frustration when you thought you might have abandoned this project because you were trying to do too much?

Haroon Siddiqui: No, no, it’s one of those things. It envelopes you. You know you’re into the book when you can’t sleep at night, right? You know, you’re into a book when you have pieces of paper right next to your bed that you get between them. Oh, this is a great idea. Write it down. See, if you don’t write it down by the morning, it’s gone. So this book has been written on sheaves of papers like this. You know, these papers are all over this house for the last five years or so.

AR Malik: Your wife of decades Auntie Yasmine is also an incredibly accomplished person that we, we always, looked up to her, not only for her incredible intelligence and poise, but her hospitality and care. What did she make of this five year process that you went through?

Haroon Siddiqui: She is sparse with her praise.No, she thinks it’s fine.

AR Malik [00:59:20] You have some wonderful and lovely moments between you and her and some beautiful pictures that also reminded me. There’s a picture of you and Auntie Yasmine from 1992 on one of the pages, and I looked at it and I had to look again, because, you know, that was 1992, and I was kind of thinking, you know, oh, Uncle Haroon, let’s we’d kind of look like the age we are kind of now and even younger and, we rarely thought of our parents as being young. They were always older and yet. You were young and youthful and, and, you also had the patience to put up with precocious kids like me.

Haroon Siddiqui: And mine. Children are a blessing from God, you know. So we’ve been blessed and God has been kind and we are lucky.

STING

AR Malik: You know we always finish up our conversations reflecting on someone who I know is so important to you, Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi.

Uncle Haroon, tell me about a joy or a meanness that recently came to you as an unexpected visitor.

Haroon Siddiqui: Unexpected visitor? my grandchildren. (laughter)

AR Malik: That’s beautiful.

Haroon Siddiqui: And a great joy. That’s one.

AR Malik: In light of everything that we’ve talked about and everything that you’ve said. What are your hopes and aspirations for those children, this, this milieu that in some ways, you and your generation helped create? Do you feel hopeful for them in a time where hope feels like it’s at a premium sometimes.

Haroon Siddiqui: No, no no, no, I’m an unrepentantly optimistic Canadian. Absolutely. We are blessed. We don’t realize. So this idea that we have, it’s a different thought, but the idea of victimhood. Which is a very modern idea. We are a culture of victimhood. The idea of victimhood, arguably, is unIslamic. We live in Parliament. This is a blessing from God.

AR Malik: A place, a place of safety and security.

Haroon Siddiqui Place of safety where you can thrive. You know the challenges. Of course. Life is full of challenges. So I’m totally optimistic.

AR Malik As you’ve been talking, you know, I’ve been feeling like, in a way, this book is the wrap up. You know, you’re looking at your life and you’re putting it all together. But my prayer is that you talk about thriving. May you always continue to thrive. And your voice and your experience is ever necessary, and, God willing, will have it for a long time.

Haroon Siddiqui: Inshallah.

AR Malik: Thank you, Uncle Haroon, for being on This Being Human. This has been such a. It’s been an honor and a pleasure.

Haroon Siddiqui: Thank you for having me.

THEME UP/ UNDER

This episode marks the beginning of Season 4 of This Being Human and we are excited to be back.

There is a link to Haroon’s book in the show notes. Make sure it’s on your “must read” list for 2024.

This Being Human is from the Aga Khan Museum. Through the arts, the Aga Khan Museum sparks wonder, curiosity, and understanding of Muslim cultures and their connection with other cultures.

This Being Human is produced by Antica Productions in partnership with TVO. Our associate producer is Emily Morantz. Our executive producers are Laura Regehr and Stuart Coxe.

Mixing and sound design by Phil Wilson. Our associate audio editor is Cameron McIver. Original music by Boombox Sound.

Shaghayegh Tajvidi is TVO’s Managing Editor of Digital Video and Podcasts. Laurie Few is the executive for digital at TVO.