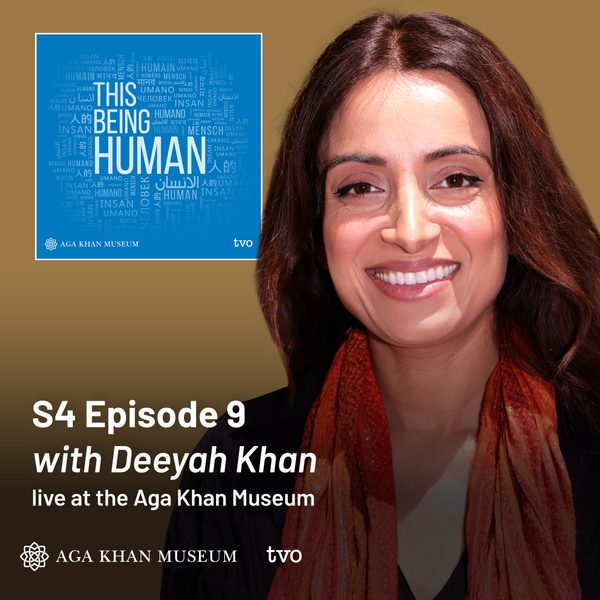

This Being Human - Deeyah Khan

Last month, we had our second ever live-recording of the podcast with the incredible filmmaker, Deeyah Khan. In front of a live audience at the Museum, Deeyah and Abdul-Rehman spoke about her remarkable journey from being a music artist to becoming a powerful voice against extremism through film. In this episode, Deeyah delves into her experiences engaging with white supremacists and jihadis, offering an unfiltered look at the roots of their beliefs and the power of empathy. Her films, including encounters with former extremists, have not only shed light on the psychology of hate but have also sparked moments of transformation for her subjects. Throughout the conversation, Deeyah reflects on the importance of empathy, love, and humanizing others as acts of defiance and resistance. She discusses the personal impact of her work, including how motherhood has deepened her commitment to creating a better world.

The Museum wishes to thank Nadir and Shabin Mohamed for their founding support of This Being Human. This Being Human is proudly presented in partnership with TVO.

MUSIC

Abdul-Rehman Malik (VO): Welcome to This Being Human, I’m your host Abdul Rehman Malik. On this podcast I talk to extraordinary people from all over the world, whose life, ideas, and art are shaped by Muslim culture.

MUSIC

Deeyah Khan: Hope is an act of defiance. So is love. So in time of hate and in time of division and fear, love becomes resistance.

MUSIC

Abdul-Rehman Malik (VO): Deeyah Khan is an Emmy and Peabody Award-winning filmmaker, a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for Artistic Freedom and Creativity and a Global Pluralism Award Laureate. Born in Norway to Pakistani parents, Deeyah’s journey has been anything but conventional. I first encountered Deeyah as a pop star. As a culture critic for the BBC, I reviewed her 2006 music video “What Will It Be?”. The song and the video were responding to threats she had received because of her public image as a musician and social critic. It was provocative, for sure, challenging conservative religious values in her own community. As it turned out, that was Deeyah’s last single. Her work has led her to producing and directing powerful documentaries that bring to light issues of extremism, racism, and gender-based violence. She has consistently used her voice to foster understanding and empathy in a way that is thoughtful, honest, and sometimes self-critical. In this live-taped episode at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Deeyah shared with me her personal and professional journey, her encounters with extremists, and her unwavering belief in the power of empathy and human connection. Her work has not only changed minds, but it’s also transformed lives. Join us as we delve into the stories behind her groundbreaking films and explore the profound impact of her mission to humanize even those we see as enemies. This is a conversation you won’t want to miss.

MUSIC RESOLVES; APPLAUSE

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Deeyah. I’ve been following your career a long time, so this conversation feels incredibly special. And you’ve clearly been on a journey. As an artist, as a filmmaker, as a storyteller. How do you track that journey?

Deeyah Khan: Oh, wow. First of all, thank you. I guess if I had to say it really briefly and try to distill it all, I would say I spent the first half of my life trying to fulfill and meet the expectations of everyone. So whether it was. This is what the expectations are of you as a woman or a girl. This is what the expectations are of you as a pop singer. This is the expectations of you as this multicultural, strange looking child born and raised in Norway, in sort of the sea of blond and blue eyed people. This is what an immigrant is like. This is what you people are like. All this, I tried to contort myself and try to do everything that I could to meet those expectations, and yet always finding myself falling short. I’m never good enough. Never this enough. Never Muslim enough, never Brown enough, not Norwegian enough. So my father, because of the experiences of racism that he faced and his friends faced in Norway, he just had it in his mind that I needed to be a singer. I don’t know why. He didn’t go for the doctor and all the usual stuff that our parents go for, right? But he just loved the arts. He absolutely loved the arts. And he had it in his head. And he gave me this long speech when I was about seven years old. He said, look, it doesn’t matter what education you get, it doesn’t matter how well you do in school, if it’s between you and a white person going for that job, the white Norwegian will get that job and not you. So there’s only two professions that I can think of where if you work hard enough and long enough, you will make it eventually. And he said, one is the arts and second is sports. And he said, sports I know nothing about. So it’ll be the arts, and within that, it’ll be music, because that was his passion. So he brought home North Indian classical musicians, Pakistani traditional musicians from the Qawwal form of classical music. So I trained with some of the best people. With Ustad Fateh Ali Khan from from the Patiala gharana in Pakistan, with Ustad Sultan Khan from India, Ustad Shaukat Hussain Khan, I grew up-

Abdul-Rehman Malik: And these musicians were coming to your home, Deeyah?

Deeyah Khan: To my home, yes.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: That’s incredible.

Deeyah Khan: In Norway. Yeah. Well, I also had to go to Pakistan to become the shagird, the disciple of Ustad Fateh Ali Khan initially, to Lahore. And initially he wouldn’t take me actually as a student because he said that you children who are growing up in foreign lands, you do not have the discipline that it takes to study our music. You don’t have the patience and you’re not going to work hard enough. And secondly, you’re a girl, so you’re a bad investment because you will get married. You will not continue the line for us. So no, I don’t want you as a student. So I had to prove myself over and over and over. He would sit there and he would sing things to me, and I had to constantly—and he would laugh! He’s like, she’s keeping up! And eventually he’s like, okay, I’ll take her. And I eventually became his favorite student, actually. So in that first part of life, you know, I try to be the good this and the good that, the good everything. And then I had some very negative reactions. The more prominence that I gained within the public space in Norway, the more backlash started against me from the more conservative people within my parents community. To the point where it started moving towards death threats, and targeting my family very, very specifically and very aggressively and very consistently to the point where I—this is why I left and I moved to London, and then some of the same stuff started following me in London. And that’s when I did that video out of a lot of anger, a lot of…

Abdul-Rehman Malik: I remember that.

Deeyah Khan: Heartbreak.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: It was visceral.

Deeyah Khan: Yeah, but a lot of other—but a lot of people in the UK didn’t necessarily know why I was doing it. Right? So for me it was just, ugh.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: It was cathartic, wasn’t it?

Deeyah Khan: Kind of a just. Yeah, just trying to get it off myself. Trying to get rid of it somehow and trying to draw a line in the sand. So. I tried this thing, this music that was his dream and was never mine. Even though I love music. But it made me hate music, actually. And then eventually I found myself sitting in Atlanta, in a house that a friend of mine owned. And I sat on this beige sofa looking at a beige wall, just staring, just thinking…all I’ve ever done, all I’ve ever studied, all I ever was ever trained in was music. And I can’t even do that. I get death threats for something that’s his dream. I’m not willing to take a bullet for that. And I was so lost and I was so broken. And I remember thinking, there’s nothing else I know how to do. So I started volunteering for organizations in London and in Bradford, in different places where I would support some of our young kids who were going through different things in their lives. And eventually, I started feeling so frustrated that I…this is how I returned to art again, because I thought, I have to tell the stories and experiences the children like us, who live between cultures, experience.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Tell us more about that, Deeyah, because, you know, those places are familiar to me. But might not be familiar to all of us. As you went into these communities and you’re working with young people at this incredibly politically pointed time when, you know, we used to play like bingo. And bingo would be like, how many days in a row are Islam and Muslims on the front page of, like, every major newspaper in the United Kingdom? And the day it wasn’t, like, you’d go out and buy cake. It was like a celebration.

Deeyah Khan: Which was very rare!

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Like, oh, we didn’t make the papers today! When people used to ask me my profession, say,, what do you do? I’d say I’m a Muslim. Because in those days, that was it. You were valued and devalued because of that identity. But you’re going into communities. You’re spending time in…

Deeyah Khan: With our kids.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Youth circles and young people. What were you hearing from them, and why was that experience of hearing what they said so important to the next steps that you took in your own journey?

Deeyah Khan: So what I was hearing and what I was confronted with a lot was similar experiences to mine on one level, which is, not getting to live and breathe and be who you are. Both because of your family’s traditions and culture and expectations, and then also your country’s expectations and prejudices and the boxes that they have had for you. And finding themselves, ourselves, sort of collapsing and getting crushed in between. And the way that that would express itself in the lives of some of these young people that I was working with was some of them were being put into marriages that they didn’t want to. Some of them were being treated horribly outside, you know, being arrested, being mistreated just because I’m a young Muslim boy.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: It was that, it was a time of surveillance culture, wasn’t it?

Deeyah Khan: It was, it was. But the part of the problem with the outside becoming so inflamed and so toxic was a lot of the things that were happening inside, we couldn’t say out loud. Right? Because what are the Brits going to say? Right? They already hate Muslims. Now, we can’t say this that’s going on with me because it’s going to make us look even worse. Right? So all those responsibilities and those calculations and those very, very difficult decisions were impossible for most of our young people. Right? So what I started realizing is what I need to do for my own sanity is to speak the truth. And what is right is right. What is abuse is abuse. What is wrong is wrong. It doesn’t matter what time we are living in. We have to take a stand. Otherwise, we are doing a disservice to our own young people who are suffering and struggling and have no way to seek the help or the support that they need. Right?

APPLAUSE

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Tell me about the first film project that emerges from these truths that you’re embracing.

Deeyah Khan: So to me, the consequences of us not understanding each other was that our kids were suffering, right? So I wanted to try and explain to people, both to our parents and that side of the community and to our countries. That when we don’t understand and when we don’t care about all of our kids, no matter what they look like, then the consequences are devastating and sometimes deadly. So I decided I would go to the absolute extreme to explain this properly, because the subtleties are harder for people to understand. So I decided to make a film about what people call honor killings. So essentially young people who are killed for transgressing the family norms and traditions and expectations and bringing dishonor and shame upon the larger group. And the larger group, family, community feeling that this person should be killed as a result. So I found many different stories that I was going to put into this film. I’d never made a film in my life. Had never picked up a camera. I had no idea how to edit or do anything like that. And I remember going to one of my music colleagues because I didn’t know people in film. Still don’t, really. And I said, look, I want to make a documentary film about this issue. You know, it’s…how hard can it be, right? I mean, can’t be that hard! And he’s like, pfft, yeah. I was like, we can figure it out, right? He’s like, pfft, yeah.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: You always need friends like that!

Deeyah Khan: Yeah, exactly. You do, you do.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: You gotta have that friend who’s gonna say, it’s gonna be easy, let’s do it.

Deeyah Khan: And they’re often in music. That they’re they’re of, you know, kind of the, yeah! Make it. Let’s just make it ourselves. And, you know, so I bought this crappy little camera. Went online, did some tutorials and things like that. Tried practicing lighting on a friend’s dog, which was a terrible idea because the dog never sat still. But anyway.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: That was a terrible idea.

Deeyah Khan: That was a horrible idea. Horrible idea. And didn’t have money to make the film. It wasn’t commissioned, wasn’t anything like that. But I decided to make it about one story instead of the multiple stories that I was looking into. And the way I chose the one story was this young woman named Banaz Mahmod, who was the daughter of Iraqi immigrants in south London. She’d been put into a marriage with a very, very violent older husband who treated her terribly, and she tried to leave, and the family consistently told her to go back. She eventually decided she wasn’t able to do this anymore, so she left. In the process of rebuilding her life, she found a young man that she fell in love with, who was another young Iraqi man in south London. Fell in love. Somebody in the community, her community, saw them kissing outside Morden tube station. And the news immediately spread that this is going on. And her uncle and her father and other family members made the decision that she’s bringing dishonor on us, so she must die. But the added tragedy was that she had gone to the police in London five times asking for help, and nobody believed her. She’d even given them a list of the men she thought were going to kill her, and nobody believed her. They thought she was being melodramatic and just was lying. So this is what happens when somebody is let down by their community, parents’ community, and is let down by their country. So nobody stood up for this girl. So the reason I chose her is when I was doing the research, I met a police officer who investigated this killing. The police officer’s name is Caroline Goode. She turned the world upside down. She secured the first ever extradition from Iraq and brought back two of the murderers, which had never happened in the UK before. She did not rest, even though there were no parents. There was nobody asking for justice for Banaz. This woman just did it. She gave me this really wooden police type interview when the camera was on, and then packed everything up and we’re about to walk out and I said, why did you do it? Why did you go above and beyond for this girl who nobody was asking about? And she murmurs, she said, because I love her. And I still get goosebumps. And I remember thinking, how can you love someone you’ve never met? How can you care about somebody you’ve never met? And she said, well, she should have been loved, but she wasn’t. So I do. And she said, and I still do. And I remember thinking, this is the film, this is the story. Because in this one story of Banaz, is all the things we are doing wrong as a society, and it also contains within it what the solution is, which is we have to care and we have to love her. And the film is called A Love Story because of Caroline, because of the love Banaz chose and then how we made the film. It took us four years. I had zero money. I did nothing but just pull favors from people and begged people to be a part of it. Initially they did it as a favor to me and eventually they did it because we all started loving this girl. And fast forward, I was going to put it on YouTube, give it away for free to activists, use it as an awareness raising tool. Done. And then somebody said, oh, you should submit it to the Raindance Film Festival. I said, I’ve never heard of it. I don’t even, I don’t care, I don’t want festivals. And so they did it anyway. And I wasn’t even at the premiere. ITV was there, they saw it. They were like, we want this, we want to actually broadcast it. I was like, well, you can’t have it because you’re going to ruin it. So no, because you’re going to make it about Muslims. You’re going to make it about “those people” and immigrants, and you’re just going to make it into this horrible way of telling the story that dehumanizes her and removes any complexity and any depth. And they’re like, no, you can cut it down and just, you can do it. Just do it. I did it. I had no idea they’d submitted it to the Emmys, to the Peabodys, to all these different places. And I remember going to the Emmys, and I haven’t really said this before, but, you know, ITV wasn’t there. I couldn’t afford to go there. So my brother had brought, like a news crew from Norway who would do a brother and sister story to get to have someone pay for the tickets to go to the Emmys.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: I love it.

Deeyah Khan: Right? And they got us like this little hotel because we couldn’t afford it. And we go, and him and I are sitting, I think, in the second row. And she, they play the clip. And it’s Banaz, you know, giving a testimony to the police in the police recording. And I just. I felt so sad and so proud and just thinking about what a room her voice was being heard in today. And the next thing I hear is my brother scream, and I ducked and I just went, oh my goodness, what is it? It’s a bomb. Like, what is it? Why are you screaming? What is it? And he’s pushing me. He’s like, it’s you, it’s you. Get up, get up. And I’m going. What do you mean it’s me? He’s like, get up, get up, it’s you. It’s your film. Get up. And I just remember going, oh, what just happened? What is this? And so that was the first Emmy, and I couldn’t speak because I was choked up thinking about her. And I remember thinking, there she is. She’s going to tell her own story. She’s never going to leave me. You know, that girl…I just. It hurts my heart. That we all let her down. She sat on our buses. She was in our classrooms. She was on our streets. And we failed her. And we constantly fail more kids.

MUSIC

Abdul-Rehman Malik: I have a small favour to ask you. If you enjoy this show, there’s a really quick thing you can do to help us make it even better. Just take five minutes to fill out a short survey. This is the Aga Khan museum’s first-ever podcast and a little bit of feedback will help us measure our impact and reach more people with extraordinary stories from some of the most interesting artists, thinkers, and leaders on the kaleidoscope of Muslim experience. To participate, go to agakhanmuseum.org/tbhsurvey. That’s agakhanmusic.org/tbhsurvey. The link is also in the show notes. Thanks for listening to This Being Human. Now, back to the interview.

MUSIC OUT

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Deeyah, fast forward, and I remember in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter uprisings, the incredible global mobilization against institutional racism and police violence. There was this upsurge in right wing activity. Not just in the United States, but in Europe.

Deeyah Khan: Everywhere. Yeah.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: And I remember into this kind of milieu. I remember being on YouTube or Facebook or Instagram one day, and there pops up Deeyah Khan. And Deeyah Khan is right in the middle of a neo-Nazi protest. And I had to look twice. And I’m like, is that the Deeyah Khan that I saw ten years ago in that music video? Sure is. I said, what is Deeyah doing?

Deeyah Khan: What’s wrong with her? Yeah.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Because I felt, like, nervous as I was watching it. I’m like, someone’s going to turn around and deck her. And you were there with a camera. You were asking questions. You were inquiring about why these people were marching and saying the horrific slogans that they were. And I was also super intrigued.

Deeyah Khan: Yeah.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Deeyah, what compelled you to put yourself in such a dangerous position amongst folks for whom violence is not an option, but their bread and butter?

Deeyah Khan: Yeah. You know, I mean, from the beginning of making the films, it’s about trying to get closer to the humanity of some of the most complicated issues that we’re faced with. I have to be completely honest. I mean, it’s all a bit of a selfish exercise. This is all so that I can learn and so that I can understand why people do the things that they do. And the reason that I want to understand why is so that we can find those gaps, those little cracks where something else could have happened, where something else might happen, where we can prevent future guys from becoming like that. And if we don’t understand each other, the consequences are the consequences of Banaz. So I wanted to understand it because also I have been on the receiving end of a lot of death threats and a lot of harassment most of my life, and I’ve been very afraid of people who do that. And I’d done an interview with the BBC before I did this film where I talked about racism, where I talked about Islamophobia, where I talked about the fact that Britain was never going to be white ever again. So that clip went viral, and ended up on violent, racist websites in the U.S., that a lot of very problematic people frequented, and they started a campaign against me and said, scare her and put the fear of God in her. And let’s see if we can stop her. And that I, they also told me that I was committing white genocide, is what they were saying, by saying what I had said. And I was editing a different film at the time in London actually. And the BBC said, you have to contact the police. And I kind of laughed that off. So they sent the police to me. And the police said, you need to get away from windows immediately. And that night I had to make a decision. I can be afraid. And I can do exactly what it is that they want me to do, which is to hide or to change my behavior or to be scared, or I can make a conscious decision to not be afraid and to see if I can seek some of them out and sit with them. Not agree. We’re not going to like each other. We’re not going to, you know, find any kind of common ground. But can we at the very least get to a point where they can recognize my humanity and I can recognize theirs?

Abdul-Rehman Malik: As a journalist, you’re always seeking a deeper narrative. Like you said, some kind of understanding. Did you think you found that? Did you find that thing that you were looking for that would allow you to understand? Dare I say, connect?

Deeyah Khan: Yes, I honestly did not have high expectations. I was just thinking, can we get to this point of recognizing each other’s humanity? That is it. We’re not going to really connect. We’re not going to agree. We’re not going to find common ground. I will just get to learn a little bit and we’ll see how this goes. But in reality, what ended up happening was, you know, I ended up forming friendships with some of them, or some of them started using that term for me. We did get to find common ground, and we did get to relate and what we would relate, those points of connection, were all incredibly human and humanizing. And that was really important realization for me, because I recognized that I had also been dehumanizing people like that myself. So I came face-to-face with my own prejudices. They did. But so did I. You know, my mother and many friends ask me, you know, why do you keep doing? Why do you focus so much on darkness? And I’m actually not focusing on darkness. Which sounds maybe counterintuitive. I’m actually looking for the light, always, in the darkness. And those cracks that you’re talking about, they’re always there. And I’m actively looking for it. So I see them when they appear, but it only appears if I’m given enough time. If I’m not given enough time to sit and listen, properly listen, and properly sit with somebody, then I can’t find it. And often they don’t want me to find it, because it’s better for them that we be afraid of each other. It’s better for them. One of the guys that I ended up becoming friends with, you know, he would describe the kind of interviews and interactions he’s had with media in the past. And he said, I get to be basically the good Nazi, and you get to be the good anti-racist person and you both. We both pat ourselves on the back. We’ve both spoken past each other to our audiences, and we can both feel self-righteous. And then we leave and nothing got accomplished. And he said, nobody has sat and asked me some of the things that you’re asking. Nobody has sat and ever listened to me, ever. And he said, and you’re not here to convince me that I’m wrong. You’re not here to try to fight me or out argue me. You’re just listening. And once he felt listened to, what I would say is, it’s almost like, you know, when you wring a, wring up, a piece of cloth?

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Yeah, like a dishcloth?

Deeyah Khan: In water? Yeah. And how relaxed and soft it gets. You can, I can see now, in people that I film, that he’s done. He’s emptied out what he needs to empty. And it’s only then I feel the capacity in him then opens up to possibly be able to hear me.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Do you feel that these emerging relationships, even friendships, have led to some kind of…transformation? I mean, does…

Deeyah Khan: In me?

Abdul-Rehman Malik: No…in you. In both of you. I’m wondering out loud. If in engaging in this kind of deep, uncomfortable, but certainly very messy human conversation, do we come out the other end, one, better human beings? And do we come out less…racist, less prejudiced, less prone to violence?

Deeyah Khan: Yes. To me, the level of humiliation that people feel and the level of shame people feel, who believe in violence. If you can introduce dignity as the opposite of humiliation, something happens in people. And I think the desire for violence doesn’t entirely disappear, but it becomes a less viable option because, instead, there is room for dialog and there is room for disagreement. You know, before this film came out and when I would explain the film to people, they were like, ugh, giving a platform to white supremacists. What are you doing? You shouldn’t be doing that. And I said, I’m not. We’re having an actual conversation. We’re having a dialogue. And they were like, are you humanizing them? They didn’t want to be humanized. They’d much rather I be afraid and they stay this big, brutal symbol rather than a human being who might be broken. And who might hurt and might have come from a very, very painful place. So humanizing each other is absolutely crucial. And does transformation happen? Yeah! I didn’t think it did. Completely honestly, I didn’t think so. I was like, a Nazi? Once a Nazi, always a Nazi.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Yeah. That’s one, wasn’t what you were going in with.

Deeyah Khan: No, no, but I was going in to sincerely try and understand. And I asked him, I asked the guy, because he was like, you get one hour and then you disappear. I never want to see you again. Just go away. And five hours later, he’s basically like, we’re going to this rally, you know, it’s going to be in Charlottesville. And you know, you’re welcome to come. And I was like, yes, yes, yes. I don’t know what he’s saying, I’m going. And I thought, it’s going to be like a couple of toothless, like Klan guys or something with a couple of placards. And I go, and it’s this thing, and I’m, you know, filming with them as they’re marching in, and getting pepper sprayed by, like the anti-racists. And I’m looking at them going, what are you pepper spraying me for?! I’m just filming! You know. But there were some very, very difficult moments. You know, it was not easy. They didn’t like me. I didn’t like them. That came much later.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: How has becoming a mom informed this work? You have a one-year-old.

Deeyah Khan: Yes.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: And a six year old.

Deeyah Khan: Yeah.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: They don’t quite know yet, but mama’s doing some pretty dangerous stuff! You know, putting her life and, you know, physical, let alone mental and spiritual, well-being on the line.

Deeyah Khan: Yeah.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Has motherhood, you know, adapted, changed, amplified the things that you’ve already been feeling? Has it brought up some new stuff for you?

Deeyah Khan: You know, I feel it’s even more urgent now to do what little I can to try and just add some drops of…something, whatever I can add, into the mix because they have to walk into this world now, you know? So I feel an even bigger obligation now to do my part, whatever part I can play. But I was pregnant with the first one when I made this film. So the marching in with the Nazis, I was massively pregnant. You see, I wear big scarves and big, baggy clothes. It’s because I’m very pregnant and marching behind them, filming them. And just constantly pulling my, my, you know, sweaters up above my bump even more. And I remember, after Charlottesville, ending up at a compound afterwards where they allowed us, well, they said I was allowed to film. And I remember walking down this windy road only having a phone with me, because we decided, my colleague and I decided, not to take our cameras with us. And the guys that had been there with all the bruises and in all those clips that you see of the fights, they were there. And they started screaming and shouting at me, you know, put your effing hands up. Who are you, who are you? Put your hands up! And my colleague and I, we put our hands up and we’re there with one other white supremacist who said we were allowed to film. And we go and he disappears. Brian. And they separate myself and my colleague, and they start screaming and shouting and one of the lines of questioning from one of the guys, and I actually almost started laughing, was, what kind of Muslim are you?! And I remember going, I remember even saying, what does that have to do with anything?! He’s like, are you Shia or you Sunni or you this, and I’m going, what does this have to do with anything?! And then another guy screaming and shouting at me. And they are. Some of them are holding beer bottles and others are holding weapons that you see in war zones. And coming from the UK, I mean, we’ve barely even seen a gun, let alone these big things. And one guy gets, his nose is almost touching me, and he’s smoking a cigarette and he blows the smoke in my face and he said, are you effing pregnant? And I had to look him dead in the eye. And I said, no, I am not. And finally Brian comes back and he negotiates for us to be able to leave. And he leaves the movement after having been a white supremacist for a long time. He leaves in the course of making the film, actually. And part of the reason he left is because he felt him and I had become friends, and he didn’t like how I was treated, so he couldn’t reconcile how he felt about me, as a friend, or as a half decent human, that he started thinking I was. And then how his brothers, his white brotherhood, was behaving. He didn’t consider himself to be a bad person, but if he was with people who did that, then what does that make him? And he went through this whole thing, so he left. And that was partly because of that incident. So has it changed me, becoming a mother? I did instantly go back. Because I hadn’t told the broadcasters and my friends or colleagues or family that I was there. So that has changed. Now I tell people where I am.

MUSIC

Abdul-Rehman Malik: This is a heartbreaking moment.

Deeyah Khan: Yes.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: There’s a lot happening in the world that is

Deeyah Khan: Unacceptable.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: And truly terrible.

Deeyah Khan: Yeah. It’s unbearable. Unbearable.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: And if it isn’t the violence and the mass death, it’s that we’ve harmed our planet so irreparably that within ten, 15 years, 2 billion people, 3 billion, numbers don’t even matter when you get to that level, are in direct threat.

Deeyah Khan: Yeah.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Of almost being incinerated. As the recent New York Times bestseller put it pithily, “the heat will kill us first.” In this moment, when I think so many of us are feeling heavy, lost, we come to a place like this that celebrates culture, to institutions like the Global Center, which continue to give us hope in the possibilities of pluralism. But let’s set that aside for a moment.

Deeyah Khan: Yeah.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Is it salvageable? Are the ideals of pluralism and inclusion and creating societies of humanity and understanding. Are those ideals salvageable? You’ve been right there amongst folks who don’t believe that they are. And I’m wondering, would you, as the storyteller, as the journalist, as the human being, as the mom, as now an activist, what do you say?

Deeyah Khan: First of all, hope is one of the most important things that we have. Yeah? Without hope, there’s nothing. And the other thing is. People who want us to give up. They have to take our hope away. So it’s another reason, if nothing else, as an act of defiance, as an act of resistance, you have to hold on to hope. We have to hold on to hope. Is it salvageable? It’s not necessarily salvageable in the immediate future when it comes to institutions or leaders or, you know, people, the so-called sort of responsible people of the world. Right? The people that we tasked to be responsible with their power and to make the right decisions in these difficult moments. I think their hypocrisy, their double standards, their lack of leadership is not salvageable. But. Where it is salvageable is with us. It’s with people. It’s with Palestinians and Israelis. It’s with Canadians and Pakistanis and Iraqis and the Kurds and the Sudanese. Because it’s about people. What we have to do as people, is we have to do what Caroline Goode did about Banaz. We have to…hope is an act of defiance. So is love. So in time of hate and in time of division and fear, love becomes resistance.

APPLAUSE

Deeyah Khan: So we have to be that, and we have to practice that, and we have to extend it to people that we don’t like. We have to extend it to people that we don’t agree with and who dislike us and who hate us. Because someone has to interrupt this. And it’s always people. It’s always just average people. Nobody extraordinary. It’s just average people who do these extraordinary things and show extraordinary courage, extraordinary capacity for love, extraordinary capacity for forgiveness. And, you know, I was recently told about the story of two parents, two fathers, a Palestinian father and an Israeli father who both lost their children. And they’re standing together. Doesn’t make everything okay. Doesn’t make it go away. But those are the moments and the drops of hope and the humanity where we can go. If someone can do that, that’s what it means to be a human. I’m very, very interested in women and women’s rights and women’s movements around the world. And I look at some extraordinary women in our parts of the world who face some absolute impossible battles. But they smile, they sing, they dance, they laugh. They don’t give up. So giving up is not just the political or the justice side of it and the activism side of it. It’s also being fully human, being fully alive, and not letting that go. When I sat on that beige couch, the decision that I made when I was volunteering, before I started volunteering, is that I don’t know where my life is going to take me. But what I do know is the rest of my life. The last half of my life. I’m going to spend it living from my heart. Whether that means I eat every two days. I don’t care. But I will always try to live by my principles and live with my heart, live with love, and the rest of it, I don’t care, I really don’t care. And I’ve had people go, oh, this will be good for your career. And I keep going, I don’t care, I don’t care, I want to spend the little time I have here, in this life, to just do the right thing and to do the best I can do. That’s it. And for people to know that it is possible. And we owe it to ourselves, and to this life that we’ve been given, to do our best. People in dire, dire, horrific circumstances still show their humanity. They’re showing it to us right now. So who are we to give up? They hold on to it, and we must hold on to it, too. They’re facing death and they still hold on to their hearts. So we must too. But our obligation is something else. It really is. And especially in this moment, our obligation is to live out loud and to do it properly and fully and as centered in humanity as possible. And we fall short. And we fall short and we stumble and we make mistakes and we say the wrong things and we do the wrong things. But then we get up again. And then we try again. And then we try to do better. It’s contagious. Hope is contagious. Just like fear is. Love is contagious. Just like hate is. So we have to be those agents. Especially now.

MUSIC

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Deeyah, tell me about a moment of joy or a meanness. Your choice. Tell me about a moment of joy or meanness that came to you recently as an unexpected visitor.

Deeyah Khan: Hmmmm…recent. How recent? Recent, like a year, recent?

Abdul-Rehman Malik: It’s open to interpretation. We’re not hard and fast about this.

Deeyah Khan: So you’re not being like, super…okay.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: It’s an impressionistic question, Deeyah.

Deeyah Khan: Well, I mean, it’s hard for me to…I mean, the birth of my second child, is a, it’s a gift. You know, lots of miscarriages. Difficult moments before. And I hoped for her. Wished for her desperately. And she came. And I thank her every day for choosing me and for coming to me. And, you know, getting to be here. Getting to meet you. I really, really think this moment is so important. I mean, not literally right now, but this, this where we are in our world right now. And I think it’s so important that we do this more and that we listen and we speak and we try to understand. And we try to gather our people. And our people, meaning all of us. And I think expanding the meaning of us, that it’s not just me and my daughters and my children or your child. You know, our family is a much bigger family. And to try to…we have to do better. We really do. This moment is requiring a lot from us. We’re not really doing it. We need to do it more. So this is very meaningful. This is an unexpected, really, really wonderful moment. So I appreciate it. And some of the people I’ve gotten to meet. It’s wonderful. And, you know, getting to know you. So many of you. So I’m grateful for that. It helps me hold on to the importance of, we’re in it together. And we need all of us. Really we do. And all our differences are needed.

MUSIC

Abdul-Rehman Malik: We really appreciate this, Deeyah.

Deeyah Khan: Thank you.

Abdul-Rehman Malik: Please join me in thanking Deeyah Khan.

APPLAUSE/MUSIC

Abdul-Rehman Malik (VO): To learn more about Deeyah’s amazing films, you can go to deeyah.com. This Being Human is presented by the Aga Khan Museum. Through the arts, the Aga Khan Museum sparks wonder, curiosity, and understanding of Muslim cultures and their connection with other cultures. This live event was a collaboration with the Global Centre for Pluralism.This Being Human is produced by Antica Productions in partnership with TVO. Our senior producer is Imran Ali Malik. Our associate producer is Emily Morantz. Our executive producers are Laura Regehr and Stuart Coxe.Mixing and sound design by Phil Wilson. Our associate audio editor is Cameron McIver. Original music by Boombox Sound. Shaghayegh Tajvidi is TVO’s Managing Editor of Digital Video and Podcasts. Laurie Few is the executive for digital at TVO.