Click on the image to zoom

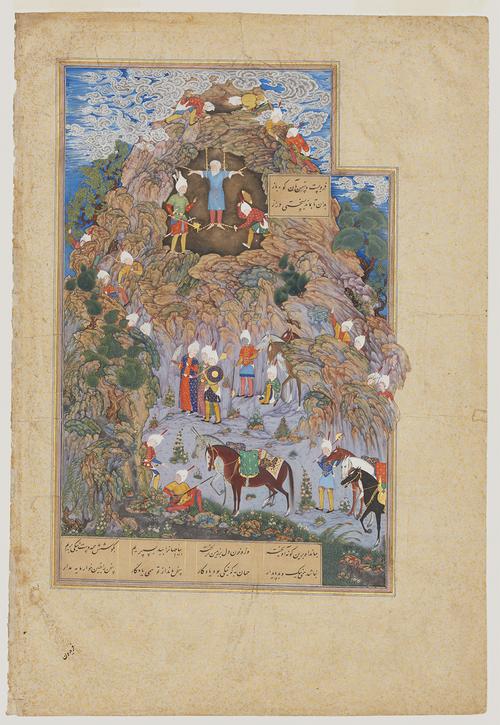

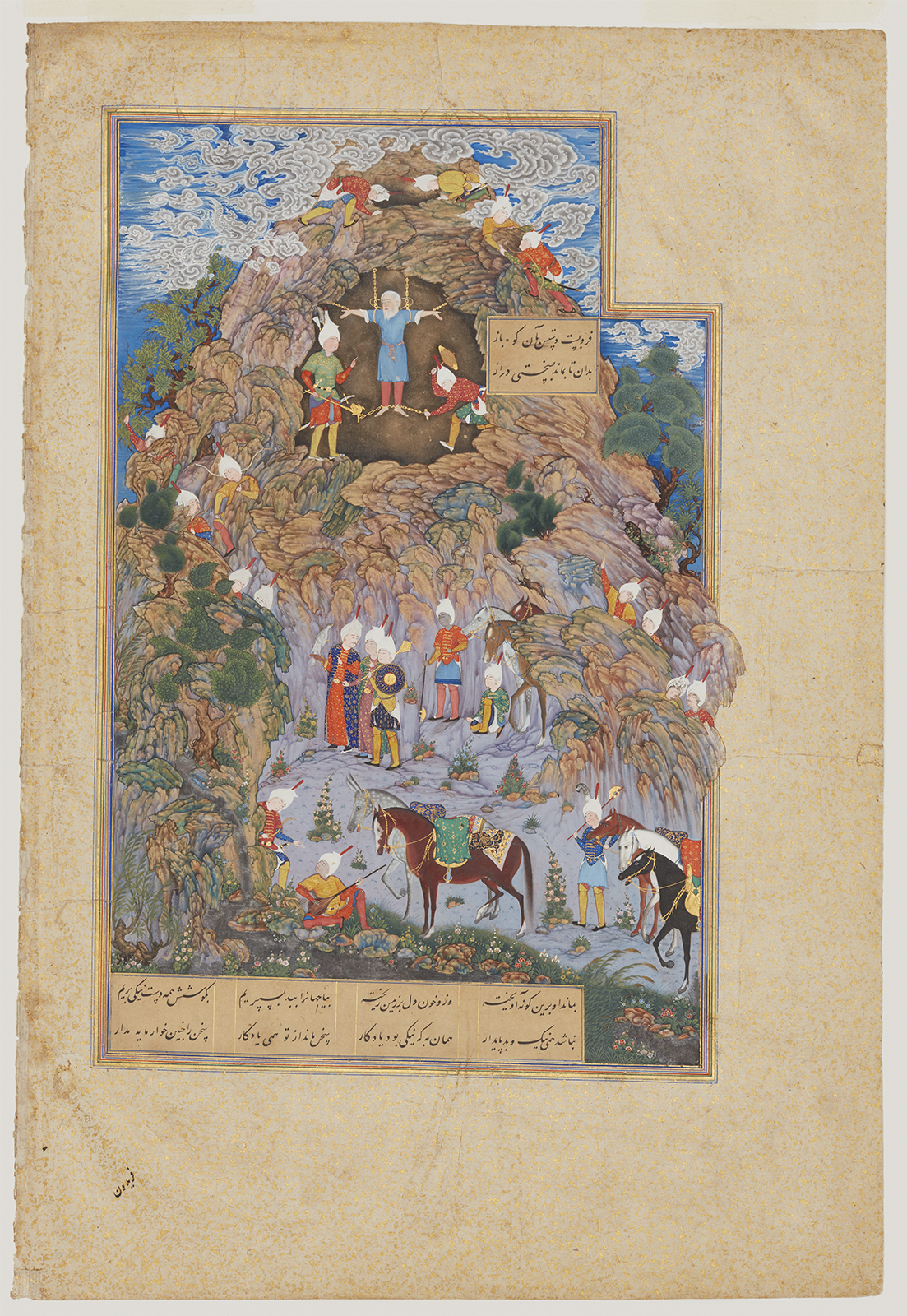

The Death of Zahhak

Folio from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-76)

- Accession Number:AKM155

- Creator:Attributed to Sultan Muhammad

- Place:Iran, Tabriz

- Dimensions:46.8 x 32.3 cm

- Date:ca. 1535

- Materials and Technique:Opaque watercolour, ink, and gold on paper

Illustrations from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), the second shah of the Safavid dynasty, represent the pinnacle of 16th-century Iranian art. In vivid detail, they complement the verses of Abu’l Qasim Firdausi, whose epic poem, completed in 1010, recounts the history of all of Iran’s shahs (kings) up to the Arab conquest in 642 AD and the country’s adoption of Islam. AKM155 (folio 37 verso) depicts the terrible fate of Zahhak, who, as a young man, came under the spell of the evil Ahriman. Ahriman appeared to Zahhak in the form of a congenial fellow and convinced Zahhak to murder his father, an Arabian king. Once Zahhak had taken control of his father’s lands, Ahriman reappeared in a different guise, this time as a cook. So pleased was Zahhak with his new cook’s culinary skill that he allowed Ahriman to kiss his shoulders. Ahriman then vanished, and on the very spots where his lips had touched Zahhak, two snakes emerged. No doctors could cure this growth until one, again Ahriman in disguise, prescribed a daily diet of human brains for the serpents. Thus began Zahhak’s reign of terror, which spread from Arabia to Iran with his conquest of that country. Zahhak’s evil slaughter and unjust rule continued for many years until ultimately a young man named Faridun, whom Zahhak had seen in a dream, led an army against the king. Eventually Faridun brought his ox-head mace down on Zahhak’s head, immobilizing him. Zahhak was then bound and taken to a cave on Iran’s highest mountain, Damavand, where he was doomed to hang from chains for eternity.

Further Reading

Attributed to Sultan Muhammad,[1] who created the famed “Court of Kayumars” (AKM165), this painting synthesizes the pictorial influences of Herat, Shiraz, and Tabriz that had occurred by the mid-1530s. Sultan Muhammad here seems to have altered his own style and helped establish the direction for 16th-century Safavid court painting. Zahhak is depicted at the top of this dense composition. In the painting’s foreground, figures rest on a hunt, seemingly oblivious to Zahhak—except for one man, who points upwards to the cave. With this gesture, the two areas of the composition are joined, conveying a moral that the accompanying text affirms: do good, for it is the best monument one can leave behind.

It has been argued that “The Death of Zahhak” dates to around 1535 and is Sultan Muhammad’s last contribution to the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp (folio 37 verso). By the mid-1530s, the style of Safavid court painting had matured, and some of the hallmarks of Sultan Muhammad’s own idiom had evolved. For example, compared to “The Court of Kayumars” (AKM165), this painting features fewer grotesque faces hidden in the rocks, and in some instances, the scale of the faces has increased. Above Zahhak’s head to the left, a long-nosed human face peers out behind a rock, while at the left of the cave next to Faridun’s leg is a large bear’s head; a few more faces appear in the rocks to the right and left of the hunters. Sultan Muhammad has still incorporated animals in the clouds, but here the one or possibly two dragons at the left are larger than the cows in “The Court of Kayumars.”

As with the Kayumars painting, the composition of “The Death of Zahhak” forms a tall oval. However, though some rocks extend slightly over the right-hand margin, the upper margin has been extended to contain the top of the mountain and the sky, producing a more subdued effect. Overall, the compositional choices in “The Death of Zahhak” result in a somewhat more sombre mood than that produced by “The Court of Kayumars.” The compositional choices and the synthesis of regional painting styles in this painting are hallmarks of the mid-1530s’ idiom.

Introduction to the The Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, by Abu’l Qasim Firdausi (d. 1020), Iran, Tabriz, 1525–35

In 1010 AD Abu’l Qasim Firdausi of Tus in northeastern Iran completed the Shahnameh (Book of Kings). Consisting of approximately 50,000 rhyming couplets, this epic poem recounts the history of all of Iran’s shahs (kings) up to the Arab conquest in 642 AD and the country’s adoption of Islam. A large part of the poem focuses on prehistoric, legendary kings, some of whom ruled for hundreds of years and established human knowledge of everything from fire to weaving. Later shahs who appear in the poem act in accordance with the historical record or, like Alexander the Great, are treated as if they were Iranian. Kings and heroes, soldiers and lovers, monsters and demons all play a role in the epic, ensuring the abiding popularity of the text and its centrality to Iranian identity. Given the vast historical scope, imaginative power, and national importance of Firdausi’s epic, it is little wonder that it inspired countless works of art in all media. Illustrations from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, the second shah of the Safavid dynasty who ruled from 1524 to 1576, represent the pinnacle of 16th-century Iranian art.

The Shahnameh produced for Shah Tamasp is represented in the Aga Khan Museum Collection by ten paintings (AKM155, AKM156, AKM162, AKM163, AKM164, AKM165, AKM495, AKM496, AKM497, AKM903) out of a total of 258 illustrations in the original manuscript. It was either commissioned by Tahmasp’s father Shah Isma‘il around 1522 or by Tahmasp himself in 1524 when he came to the throne. Except for a few paintings added later, the manuscript was completed by around 1537. Three successive supervisors managed a team of painters, gold sprinklers, margin measurers, bookbinders, and other specialists gathered from all the main schools of Persian painting at the Safavid capital, Tabriz. The manuscript remained in Safavid hands until 1568, when Shah Tahmasp presented it to the Ottoman Sultan Selim II. It remained in the Ottoman royal collection until the late 19th or early 20th century, when it entered the collection of French Baron Edmond de Rothschild. In 1959 one of his descendants sold the manuscript to the American, Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., who split up the book in 1970 when he gave 77 illustrated folios to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In the ensuing years pages were sold at auction and by a London art dealer until 1994, when Houghton’s son swapped the text pages, binding, and remaining 118 illustrations with the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art for a painting by William de Kooning.

— Sheila R. Canby

Notes

[1] Not only did S.C. Welch attribute this painting to Sultan Muhammad, but also he argued that it dates to around 1535 and is the artist’s last contribution to the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp (see Dickson and Welch, vol. 1, 81). Worth noting is the darker colour of the paper on which the text is written on the verso side of this page, while the recto is consistent with most of the other folios in the manuscript. The only other illustration with the same paper colour is folio 341v, “The First ‘Joust of the Rooks’: Fariburz versus Kalbad” (AKM497), which Welch believes was added to the manuscript around 1540 (see Welch no. 27).

References

Dickson, Martin B. and Stuart Cary Welch. The Houghton Shahnameh, 2 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981. ISBN: 9780674408548

Welch, Stuart Cary. Wonders of the Age: Masterpieces of Early Safavid Painting, 1501–1576, no. 27. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. ISBN: 9780916724382

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.