Click on the image to zoom

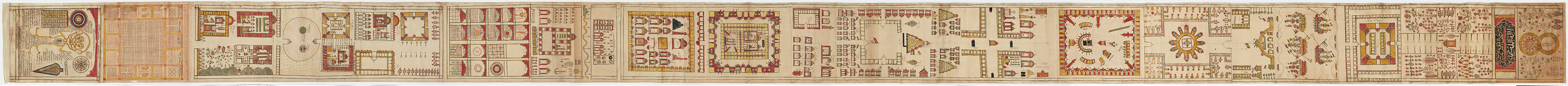

Shiite Talismanic Pilgrimage Scroll

- Accession Number:AKM917

- Creator:signed by Sayyad Muhammad Hasan Čishti

- Place:India, Probably Deccan

- Dimensions:918 x 45.5 cm

- Date:1787–88

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour, black and red ink, and gold on paper; mounted on cloth backing

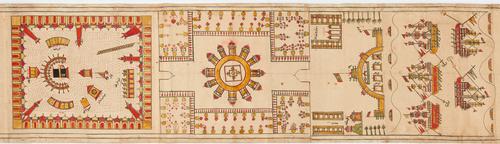

This monumental scroll measuring more than 900 x 50 cm depicts several major Muslim holy sites, such as the sanctuary of the Ka‘ba and other pilgrimage stops of the Hajj in and around Mecca, as well as Medina, Jerusalem, Karbala, and Najaf. Arranged vertically, these buildings and sites are all oriented towards the Great Mosque in Mecca with the Ka‘ba at the centre; in this manner, the Ka‘ba functions like a magnetic pulse located in the first third of the scroll. Two visual sequences—one starting at the beginning of the scroll marked by a colophon cartouche, and the other at the end of the scroll marked by a calligram (here, a human figure made of calligraphy)—comprise its composition. This scroll has previously been thought to be a Hajj certificate,[1] a document affirming that an identified individual or his/her representative has fulfilled the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca and surrounding sites.[2] However, recent research confirms that a considerable portion of the visual repertoire and its inscriptions was composed to increase magic and talismanic functions of this scroll within a clear Shiite context.

Further Reading

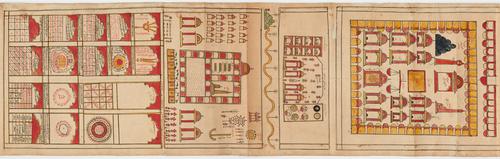

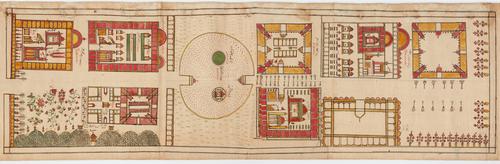

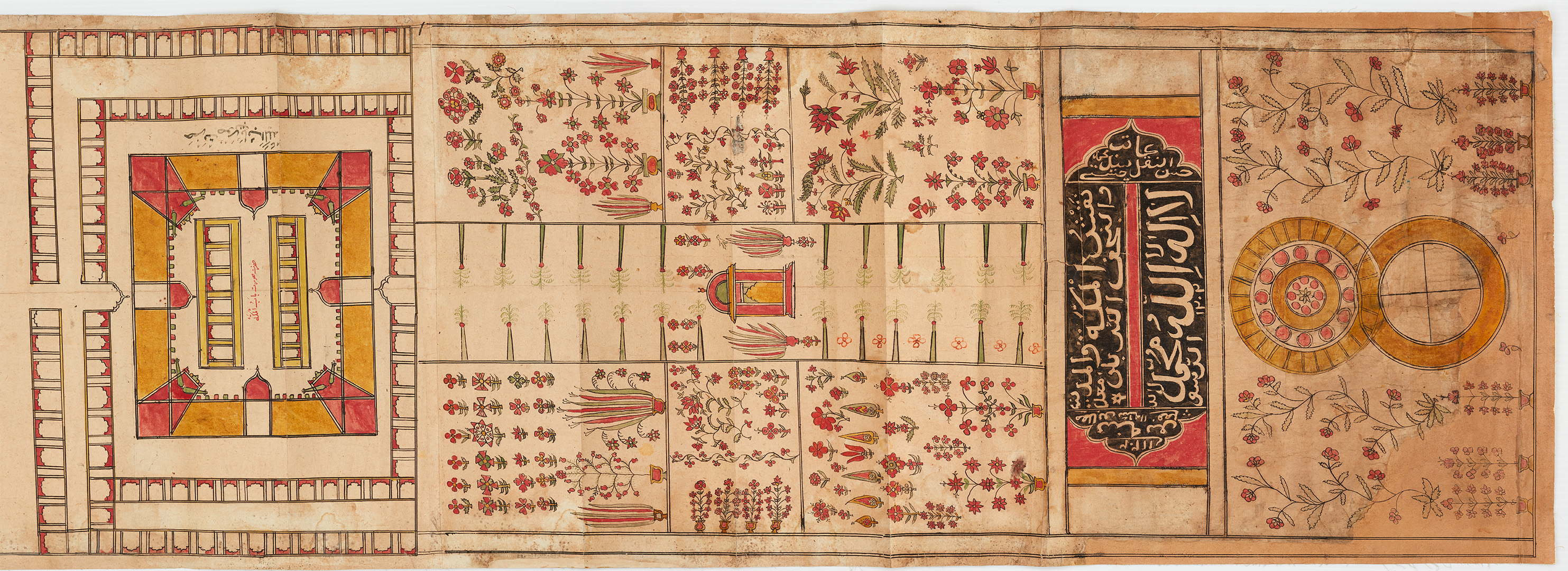

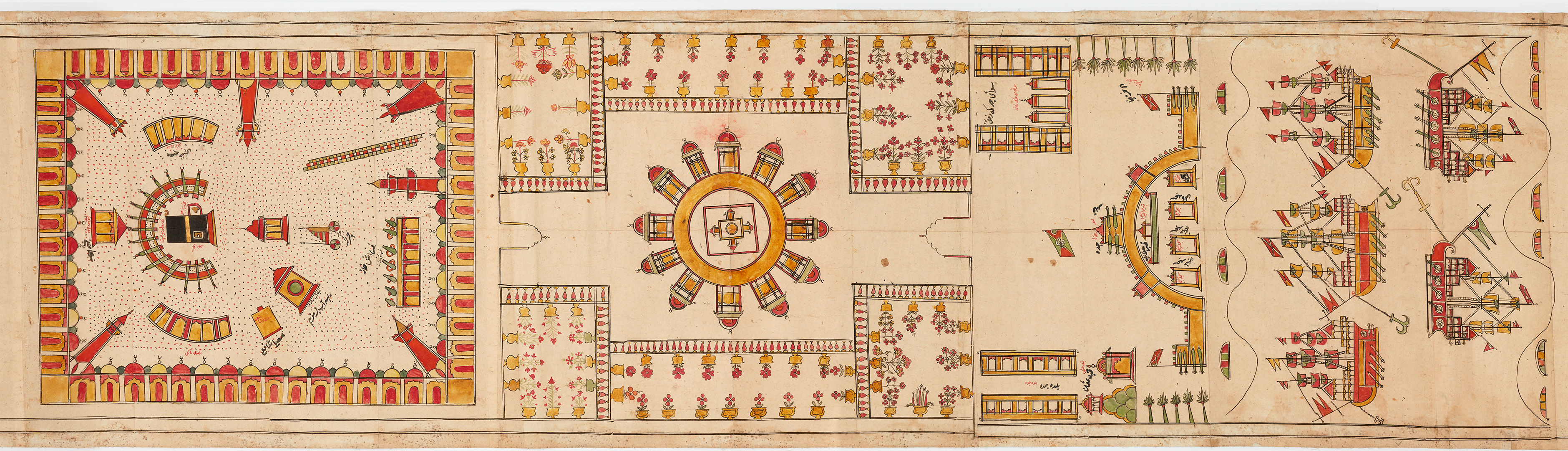

Rendered on buff paper that has been backed with white cloth, the various sites, buildings, and floral compositions are all skilfully drawn and vibrantly painted in red, green, and yellow tones with black outlines. Many inscriptions [3] in red and black identify the sites and buildings or type of architectural elements depicted, such as a minaret, a mosque, or a pool.[4] The longer inscriptions are in Persian, together with passages from the Qur’an and prayers in Arabic. Portrayed in a two-dimensional, bird’s-eye view, architectural sites and buildings are divided into subsections resembling bento boxes and arranged in the conservative, vertical format of traditional Hajj scrolls and certificates.[5] Floral and vegetal compositions as well as images of ships are shown frontally. A simple doubled margin in black frames the edges of the scroll. Individual sections as well as architectural elements and details are divided by double-lined black frames and borders finely executed with a ruler. The yellow and red colour palette, drawing style, and compositional approach relate this scroll to the Indian tradition of depicting the Hajj and religious architectural sites.[6] The floral motifs and compositions as well as the figural calligram relate to the artistic traditions of the Deccan plateau.[7]

A cartouche with calligraphy (Fig. 1) in reserve against a black ground with the shahada, date, and signature of the scribe presents the work as “Drawing/Painting (Naqsh) of Mecca, Medina, Najaf, Kerbalah…” However, the sophisticated visual representation on this scroll embodies additional layers of meaning. The primary association of this work is with pilgrimage, which constitutes the first and longest section (Figs. 1–4). The idea of the Hajj is illustrated by the sequence of depictions and inscriptions that follow. A central alley of palm trees with floral gardens—perhaps referring to paradise—on each side lead to Jeddah, the major port in the Hijaz. This first destination is depicted with a rectangular building, identified as the “Gate of Mecca” (probably the one at Jeddah) (Fig. 1),[8] and then a group of five large ships evoking the port, as well as the citadel of Jeddah. The emphasis given on the ships and the port of Jeddah suggests that this scroll was made for a pilgrim who would travel by sea and confirms the Indian Ocean context. From there, the path on the left leads to balad Jeddah, while the path on the right is the “Journey going to Mecca” (Fig. 2). Mecca is depicted with the Great Mosque shown as a rectangle, and details such as domed porticos, six minarets,[9] buildings representing the four legal schools of Islam, or the zamzam water bottles all converge around the Ka‘ba. This is followed by common stops of the Hajj or ‘Umrah pilgrimage,[10] such as the mas‘a (referring to the seven-time trotting and running between the Safa and Marwa hills),[11] the Ma‘la cemetery, Jabal Shaq al-Qamar (the mountain where the miracle of splitting the moon took place), Mina, or the ‘Arafat mountain (Fig. 3). Next is the fortified city of Medina with the Great Mosque in the centre. This section depicting the Hajj stops including Medina covers about two thirds of the scroll and is conceived within one same continuous double-lined border, which visually separates it from the remaining part of the scroll.

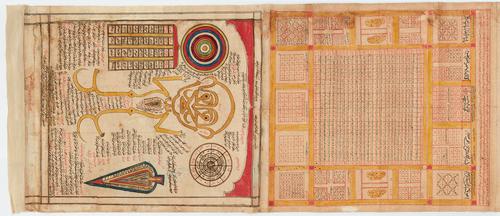

The last third of the scroll depicts Shiite pilgrimage sites and talismanic symbols (Figs. 4-6). It begins with a narrow outlined section within the middle of four domed buildings surrounded by flowers in a garden, and an inscription above it identifying it as the “straight path to Hell or Heaven.” The outlined section which follows depicts Jerusalem in a similar way as the Great Mosque of Medina, with courtyard, minbar, and four tombs. However, the walking stick of the prophet Jesus (‘asa hazrat ‘Isa) on the right side and a curving vine branch below inscribed as “Mountain of the Olives/Olive trees (Jabal Angur)[12] may identify this site. Then follows a section devoted to the seal of prophethood and other talismanic symbols, as well as prayers (Fig. 4). This part is organized as a chart with square and rectangular units, and at times polylobed arched fields. The design compares with multiple-niche prayer carpets known in the Deccan.[13] The Persian inscriptions on the upper right side reference the image or account of seal(s) of the prophet Muhammad several times. Towards the left side is the symbol of Zulfiqar with the inscribed Shiite formula in Arabic the Nadiya Ali or prayer to ‘Ali.[14] On the very left is the hand-shaped seal quoting Husayn, Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthman, and Haydar (‘Ali). Below, the inscribed text provides instructions on when, how, and where to pray to maximize one’s blessing (Baraka), emphasizing the importance of the seal of the Prophet: whoever sees it and prays will be cleansed of sin, be it during life, sleep, or death, and regardless of whether one is in the fire of hell or experiencing the day of resurrection. The magic charts and the circular seals of prophethood are designed in a traditional way.[15]

The following section depicts Karbala and Najaf, the two major holy Shiite pilgrimage sites in central-south Iraq (Fig. 5). A significant section with talismanic charts follows (Fig. 6); it is introduced with a heading in red Persian script, stating that this scroll is “another kind of scroll/tablet from Imam Jafar Sadiq,” who was considered one of the authorities of magic and omen interpretation since the ‘Abbasid period. The scroll ends with a human figure calligram.

As a whole, this scroll depicts a group of religious sites that express historical significance and religious meaning. The title naqsh (drawing/painting), together with the absence of specific text relating to Hajj or ‘Umrah protocol which one would expect in such a monumental scroll, challenge the scroll’s reading as a traditional Hajj certificate. The imagery and inscriptions suggest a pronounced Shiite context that conveys multiple levels of meanings and functions. While the holy pilgrimage to Mecca and related places occupies the main portion of this scroll, a significant part is devoted to major Shiite sites, including Najaf, Karbala, and Jerusalem. The scroll is a visual reminder and guide of pilgrimage for the Shiite community, and, at the same time, it can be used for magic and talismanic purposes. The iconography and prayers aimed at maximizing protection, blessing, and cleansing from sins. The large size of this scroll renders it suitable for collective use.

— Deniz Beyazit

Notes

[1] See catalogue entry Christie’s, Arts of the Islamic and Indian Worlds, London: April 7, 2011, lot 267; Architecture in Islamic Arts, p. 62–65, 2011. Marzolph 2013, 3, refers to it as Pilgrimage scroll.

[2] The Sura al-‘Imran, 3:96–97 identifies the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca as the duty for devout Muslims: “The first House [of worship] to be established for people was that at Bakka [Mecca]. It is a blessed place; a source of guidance for all people; there are clear signs in it; it is the place where Abraham stood to pray; whoever enters it is safe. Pilgrimage to the House is a duty owed to God by people who are able to undertake it.” Hajj certificates were issued to pilgrims as well as to people who, due to a fragile health condition (sickness or age), were unable to perform the pilgrimage themselves. For references on the Hajj or depictions of Mecca, see AKM587 and AKM529.

[3] I am grateful to Maryam Ekhtiar for all her help in reading the many inscriptions of this scroll.

[4] Many of the labelling inscriptions are doubled in red and black; the black ones are often washed out. It is possible that at a later time the red ones were added.

[5] For references, see AKM529 and AKM587.

[6] See a good example in the Khalili Collection, Anis al-Hujjaj (‘Pilgrim’s companion’) by Safi b. Vali possibly Gujarat, India, ca. 1677–80 (Arts de l’Islam: chefs-d’oeuvre de la collection, Khalili, Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris 2009, 288–95). The Futuh al-Haramayn pilgrimage guides, popular in the 16th century in the Ottoman sphere, continued to be copied in the Indian Subcontinent in the 17th century and beyond. These latter have been fairly studied and might help to better assess the art and history of this scroll. For later examples, see an example from North India, dated February 13, 1703 and signed by Muhammad Zarif Sojat (Christie’s London, October 26, 2017, lot 150) and another one from Lahore, Punjab, dated March-April 1840 and signed by Muhammad Sayfullah (Christie’s London South Kensington, April 18, 2016, lot 33).

[7] Striking similarities can be drawn with the style of the floral repertoire of Bidri inlaid metalware, cut-out paper or painting; see Haidar and Sardar, New York, 2015, 120–1, 134, 138, 178, 190, 193. For the calligram, see the opening page in the manuscript Nan wa Halwa (“Bread and Sweets”), ca. 1690, made in India, Deccan, Aurangabad, in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999.157 (Haidar and Sardar, New York, 2015, cat. 170, p. 294); see also an example on a textile banner in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection, London (TXT 233), Francesca Leoni, Oxford, 2016, cat. 42, pp. 66–67. The names of Muhammad and ‘Ali have been repeated twice and composed in mirror-script to form a head, whereas in the AKM scroll, the composition extends with a body composed with Muhammad extending into limbs, legs, and hands, and Allah for the neck; and with a heart at the centre. Several of the floral motifs in this manuscript also relate to the AKM scroll.

[8] Arabic vocalized inscription in red and black as “Hazret surat bab al-Makka.” In Ottoman times there were several gates in the city walls of Jeddah; the eastern gate was the Bab al-Makka.

[9] A seventh minaret was added in the early 17th century.

[10] The pilgrimage to Mecca is only qualified as Hajj if it is accomplished during specific days of the Muslim calendar.

[11] A portion of the Surat 2:158 is inscribed, reminding that one is allowed to do/enter mas‘a whether during Hajj or Umrah: “Truly Safa and Marwa are the symbols of God. Whoever goes on pilgrimage to the House (of God), or on a Holy visit.” This Qur’anic passage relating to the Hajj also appears on the Doha scroll; see Chekhab-Abudaya, Mounia, Amélie Couvrat Desvergnes, and David J. Roxburgh, 2016, 253. However, here the following portion is omitted: “is not guilty of wrong if he walks around them. And whoever volunteers good—then indeed, Allah is appreciative and Knowing.”

[12] Persian word for olive.

[13] For an 18th-century example in the Collection of Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf, see Haidar and Sardar, 2015, cat. 151, pp. 256–57.

[14] “And there is no hero but ‘Ali, there is no sword but the Zulfiqar.”

[15] See Leoni, Oxford 2016, 45; on Magic and Divination, see also Yahya, Leiden 2016, and Ekhtiar and Parikh (forthcoming).

References

Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Architecture in Islamic Arts: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2011. ISBN: 9780987846303

Alexander, David G. “The guarded tabket,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 24 (1989): 199–207. DOI: 10.2307/1512880

Chekhab-Abudaya, Mounia, Amélie Couvrat Desvergnes, and David J. Roxburgh. “Sayyid Yusuf’s 1433 Pilgrimage Scroll (Ziyārātnāma) in the Collection of the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha,” Muqarnas 33 (2016): 345–407. DOI: 10.1163/22118993_03301P011

Christie’s. Arts of the Islamic and Indian Worlds (auction catalogue). London: April 7, 2011, lot 267

---. Islamic Manuscripts Featuring The Mohamed Makiya Collection. London: April 18, 2016, lot 33

---. Arts of the Islamic and Indian Worlds Including Oriental Rugs and Carpets. London: October 26, 2017, lot 150

Ekhtiar, Maryam and Rachel Parikh. “Power and Piety: Islamic Talismans on the Battlefield.” In Francesca Leoni, Matthew Melvin-Koushki, Liana Saif, Farouk Yahya eds. Islamicate Occult Sciences in Theory and Practice, Brill (forthcoming).

Harley, J.B. and David Woodward, eds. Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. ISBN: 9780226316352

Leoni, Francesca, ed. Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2016. ISBN: 9781910807095

Marzolph, Ulrich. “From Mecca to Mashhad: the Narrative of an Illustrated Shiite Pilgrimage Scroll from the Qajar Period.” Shangri La Working Papers in Islamic Art 5 (July 2013): 1–33, www.shangrilahawaii.org.

Nanda, Vivek and Alexander Johnson. Cosmology to Cartography: A Cultural Journey of Indian Maps. New Delhi: National Museum, 2015. ISBN: 9788186921760

Navina Najat Haidar and Marika Sardar. Sultans of Deccan India 1500 – 1700: Opulence and Fantasy. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015. ISBN: 9781588395665

Rogers, Michael, ed. Arts de l’Islam: chefs-d’oeuvre de la collection Khalili. Paris: Institut du Monde Arabe, 2009. ISBN: 9782754104012

Yahya, Farouk. Magic and Divination in Malay illustrated manuscripts, Leiden: Brill, 2016. ISBN: 9789004301641

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.