Click on the image to zoom

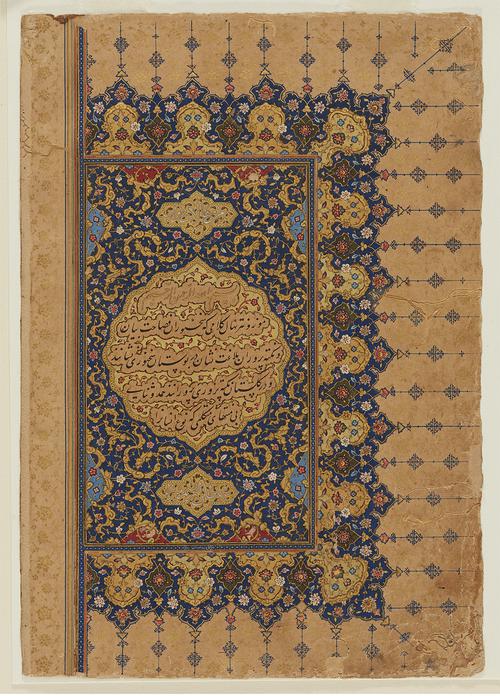

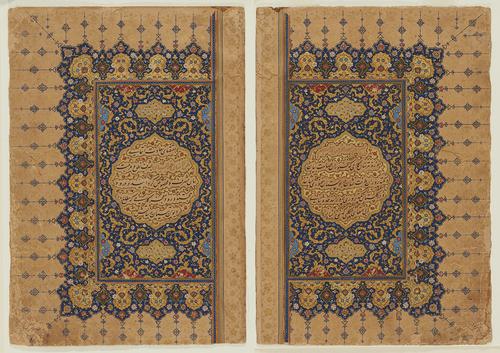

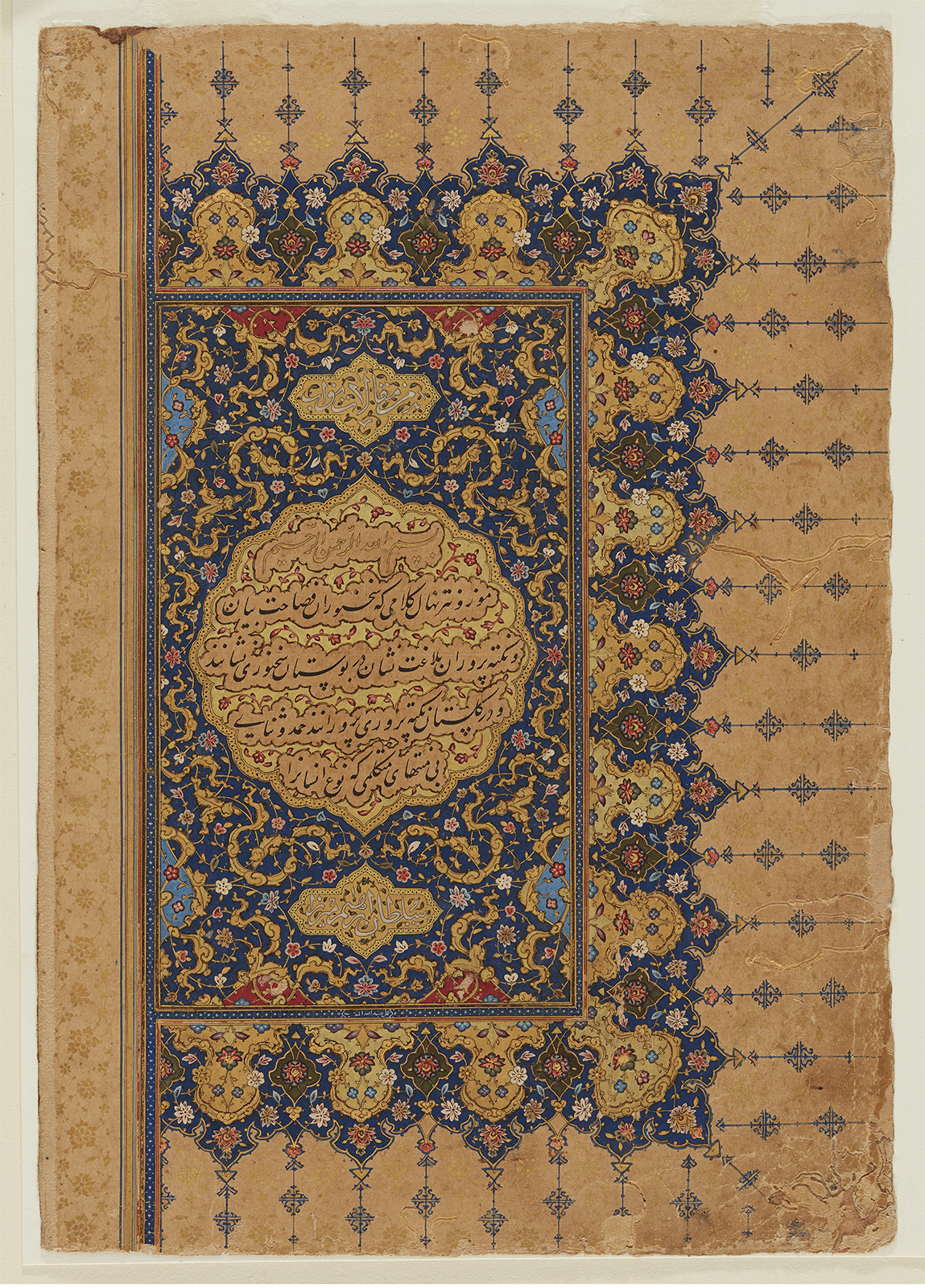

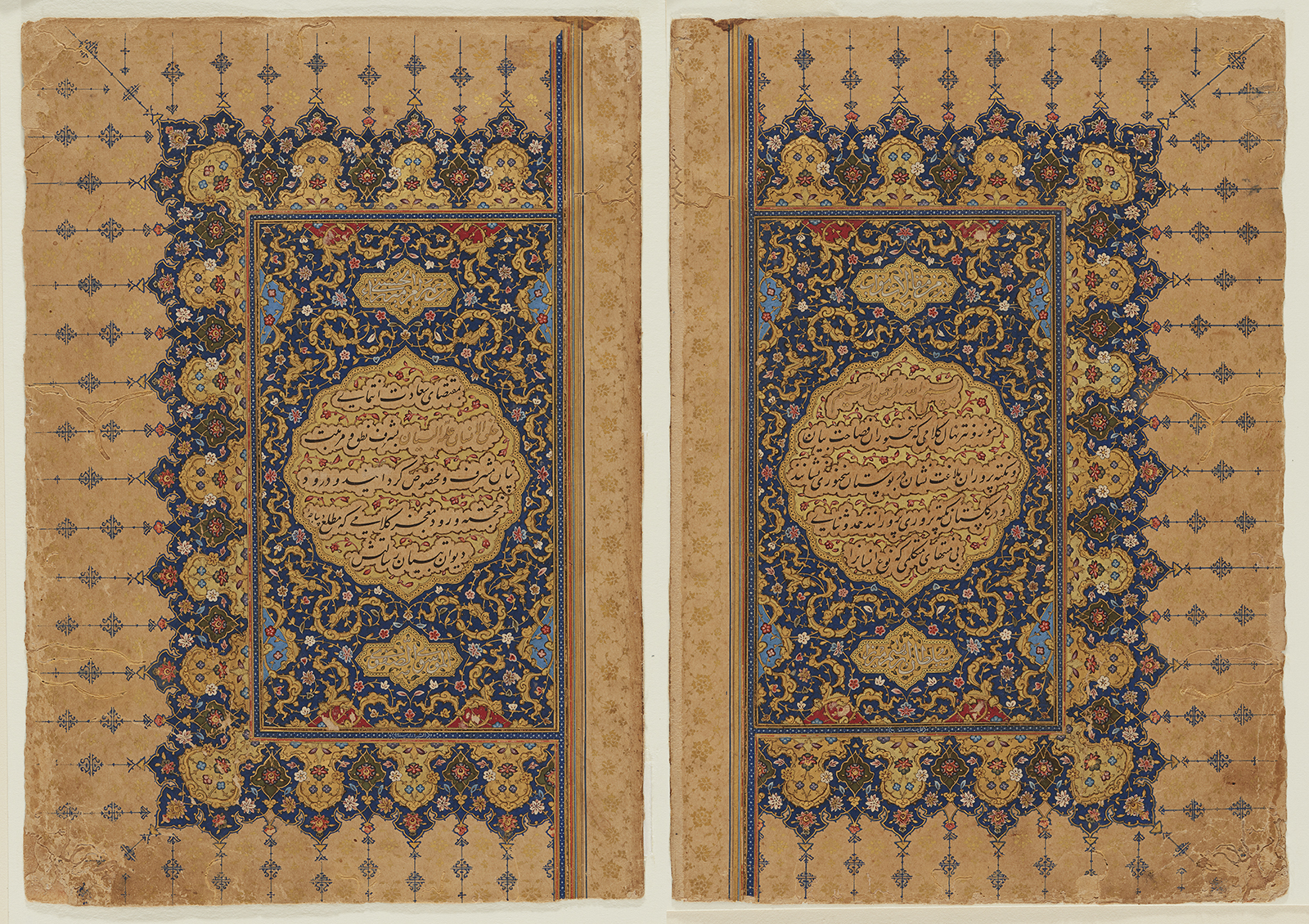

Right half of a double-page frontispiece

Folio from a manuscript of the Collected Works (Divan) of Sultan Ibrahim Mirza (fol. 1)

- Accession Number:AKM282.1

- Creator:Artist (calligrapher): `Abdullah al-Muzahhib

Artist (painter): `Abdullah al-Muzahhib

Compiled by: Gawhar Shad

Poet: Sultan Ibrahim Mirza, Persian, 1540 - 1577 - Place:Iran, Qazvin

- Dimensions:23.9 cm x 16.8 cm

- Date:1582-83 CE/990 AH

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour, ink, gold and silver on paper

AKM282.1 (Folio 1v) is the right side of a double-page frontispiece from a manuscript of the Divan of Sultan Ibrahim Mirza (d. 1577). This beautifully-decorated leaf, along with AKM282.2 (Folio 2r) opens a rare manuscript of the Divan, or collection of poems, by the Persian prince Sultan Ibrahim Mirza (1540–77), who wrote under the pen name Jahi. Like his uncle Shah Tahmasp, the second ruler of Iran’s Safavid dynasty (1501–1734), Ibrahim Mirza was an important patron of the literary and visual arts and renowned for his own accomplishments in those fields. After his death by assassination in 1577, Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s daughter, named Gawhar-Shad Begum, ordered several thousand of his verses, written in both Persian and Turcoman Turkish, to be compiled as a Divan. She then commissioned its transcription, decoration, and illustration as a volume in her father’s memory. The prince’s name appears in white thuluth script in the paired cartouches above and below the frontispiece’s twin central medallions, which themselves explain the circumstances of the Divan’s compilation in black nasta’liq script with the bismallah and a Qur’anic reference in gold. That the illumination, and possibly also the elegant calligraphy, was the work of the multi-talented Safavid artist Abdullah al-Shirazi is confirmed by his signature, written in minute white letters within in the narrow blue band surrounding the frontispiece’s central fields: “Work of ‘Abdullah the illuminator [folio 1v] from Shiraz, the year 990 [folio 2r].” Abdullah also signed and dated one of the manuscript’s six text illustrations (see AKM282.23).

Further Reading

The Divan manuscript belonging to the Aga Khan Museum consists of 87 folios or leaves, with the prince’s Persian poems arranged in three sections of different meters and rhymes, followed by a fourth series of verses in Turkoman Turkish.[1] During Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s lifetime, the classical, mystically-oriented love poetry of earlier generations began to be supplanted by a new “realist” style, so-called because the emphasis was on actual human encounters and emotions expressed in colloquial language. While 16th-century poets such as Ibrahim Mirza continued to evoke conventional themes of mystical love and longing, their realist poems employed original similes and verbal imagery to capture the passions and desires of everyday human relationships with new directness and psychological insight.[2] Sultan Ibrahim Mirza further personalized his love poetry by incorporating his pen name Jahi into amorous discourses with the subjects of his affection, into admonitions to himself about causing offense to lovers, and into plaints about the afflictions that can come with love.

While Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s poetry may not rank as the most memorable of the “realist” school, the overall artistic quality of his Divan manuscript marks it as a splendid example of deluxe Safavid artistic production. Abdullah al-Shirazi’s illuminated frontispiece is particularly distinctive, with its large centre fields; bright palette of deep blue, gold, and orange; the two alternating bands of scalloped medallions that form a unifying frame; and the blue finials and gold blossoms in the outer margins. The prince’s poems are written on gold-dusted paper set into highly-polished, salmon-coloured margins, which are decorated in gold with large pea fowl flying amid floral scrolls. Three of the four main groups of poems are introduced with brightly-illuminated titlepieces, and rectangular panels with gold cartouches separate individual poems. Small blossoms on swaying stems fill the columns that divide the verses. The second section of Persian verses, comprising ghazals (amatory poems), are further enhanced with six narrative paintings (see AKM282.19, AKM282.23, AKM282.29, AKM282.32, AKM282.36 and AKM282.43). A striking double-page pictorial finispiece depicting a princely reception scene, possibly also by ‘Abdullah, brings this beautiful volume of Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s poems to a close (see AKM282.86 and AKM282.87).

The frontispiece to Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s Divan contains the beginning of a prose preface in which Gawhar-Shad Begum explains that, after her father’s death, many of his verses became lost. Thus she “strove her utmost to gather each and every line and each and every poem in the hopes that perhaps some sympathetic person may open his lips to ask for forgiveness for them, and thus they might obtain mercy.”[3] A Safavid court chronicler subsequently reported that Gawhar-Shad Begum then sent copies of the Divan to all the lands of Iran, Turan [meaning Central Asia], the east, India and Rum [probably meaning Turkey].[4] Notwithstanding all these efforts, only one other volume of the Divan is known today.[5]

About Sultan Ibrahim Mirza

Sultan Ibrahim Mirza was the scion of the Safavid family that ruled Iran for more than two centuries and fostered many artistic developments. His life followed closely that of his father, Bahram Mirza (d. 1549), the favourite brother of Shah Tahmasp, who held royal appointments and patronized the arts of the book. Another role model was his uncle Sam Mirza (brother of Bahram Mirza and Tahmasp), who also distinguished himself as an author, artist, and art patron. After prince Bahram’s death, Sultan Ibrahim Mirza spent his formative years at the court of Shah Tahmasp,[6] who supervised his education, determined his role in Safavid dynastic affairs, arranged his marriage (to the shah’s own daughter, thus Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s first cousin), and encouraged or at least endorsed his interest in literature and the visual arts.[7] One Safavid chronicler extolled the prince as “sweet-tongued in poetry and poetics . . . and gifted in the art of metrics, rhyming and [word] puzzles.” As for his artistic skills, the same source avers that the prince had “golden hands in painting and decorating” and was regarded as “one of the recognized calligraphers of Iran.” He also displayed mastery in “bookbinding, gilding, gold sprinkling, the making of stencils and the mixing of colours.”[8]

In 1554–5 Tahmasp appointed his princely nephew and son-in-law as governor of the venerable shrine city of Mashhad in northeastern Iran. It was during his tenure there that Sultan Ibrahim Mirza commissioned a deluxe manuscript of the Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) by the celebrated mystical poet Abdul-Rahman Jami. Copied by five court calligraphers during the years 1556–65 and illustrated by an equally diverse coterie of painters, this volume is regarded today as one of the masterpieces of the Safavid period. ‘Abdullah al-Shiraz also had a hand in its decoration, as evidenced by his signature hidden within one of the manuscript’s illuminated title-pieces. [9]

By 1563 Sultan Ibrahim Mirza had fallen out of royal favour and he was removed from the governorship of Mashhad and assigned to successive posts in the much-less prestigious towns of Qa’in and Sabzivar. Despite this demotion, the prince continued his activities as a patron of the arts, and commissioned another illustrated manuscript, albeit much more modest than his magnificent Haft Awrang. [10]

— Marianna Shreve Simpson, in collaboration with Chad Kia

Notes

[1] Folios 3v-16v: qasidas (elegaic odes); folios 16v-55r: ghazals (amatory poems); folios 55v-68r: ruba’iyat (quatrains), scattered couplets and “orphaned” hemistitches; folios 68r-86r: turkiyats.

[2] Paul Losensky, “Poetics and Eros in Early Modern Persia,” Iranian Studies 42 (2009): 749.

[3] Translation by Wheeler Thackston.

[4] See Marianna Shreve Simpson, with contributions by Massumeh Farhad, Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s Haft Awrang: A Princely Manuscript from Sixteenth-Century Iran. (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997), 236.

[5] Tehran, Gulistan Library 2183, dated 989/1581–2. This manuscript also involved the participation of ‘Abdullah al-Shirazi, described in its colophon as an “old companion of the deceased prince Sultan Ibrahim Mirza.” See Simpson 1997, 420–1; Ahmad Alizadeh and Parisa Baqernejad, “Sultan Ibrahim Mirza-yi Safavi divan va sabk-i sha`iri-i u,” Bahar-i Adab: Faslnama Takhasusi-i sabkshenasi-i nazm va nathr-i farsi 6/4 (Winter 1392/2014): 213.

[6] For Shah Tahmasp, see AKM155, AKM156, AKM162, AKM163, AKM164, AKM165, AKM495, AKM496, AMK903.

[7] Marianna Shreve Simpson, “Ebrāhīm Mirzā,” Encyclopaedia Iranica 8 (1998): 74–5.

[8] See Simpson 1997), 235–6.

[9] The Haft Awrang belongs to the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (F1946.12). See Simpson 1997 for a detailed study of this manuscript, and for more on Sultan Ibrahim Mirza (227–51) and ‘Abdullah al-Shirazi (300–7 and 420–1).

[10] Simpson 1997, 240–1 and Appendix A.III.

References

Alizadeh, Ahmad and Parisa Baqernejad. “Sultan Ibrahim Mirza-yi Safavi divan va sabk-i sha`iri-iu,” Bahar-i Adab: Faslnama Takhasusi-i sabkshenasi-i nazm va nathr-i farsi 6/4 (Winter 1392/2014): 213.

Losensky, Paul. “Poetics and Eros in Early Modern Persia,” Iranian Studies 42 (2009): 749.

Simpson, Marianna Shreve. “Ebrāhīm Mirzā,” Encyclopaedia Iranica 8 (1998): 74–5.

—, with contributions by Massumeh Farhad. Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s Haft Awrang: A Princely Manuscript from Sixteenth-Century Iran. Washington, DC, Freer Gallery; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997. ISBN: 9780300068023

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.