Click on the image to zoom

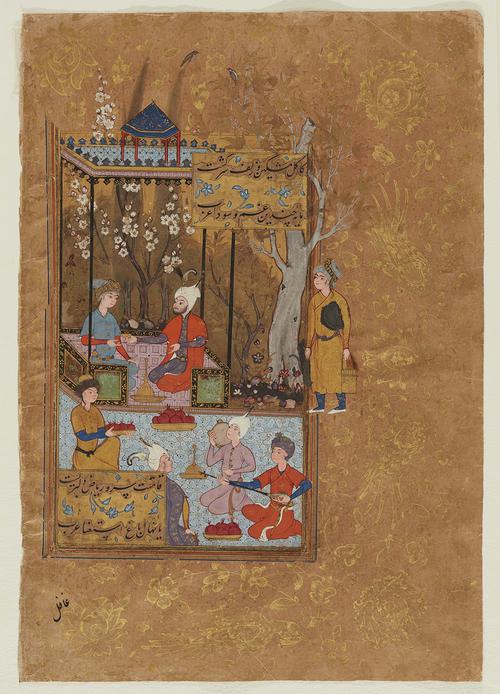

Princely Entertainment in a Garden

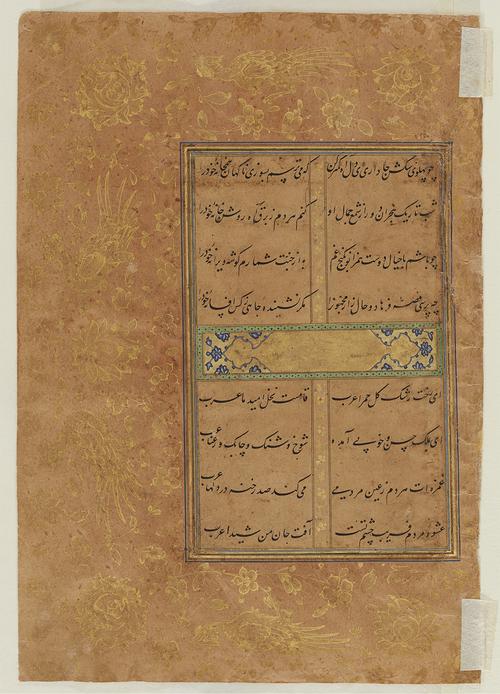

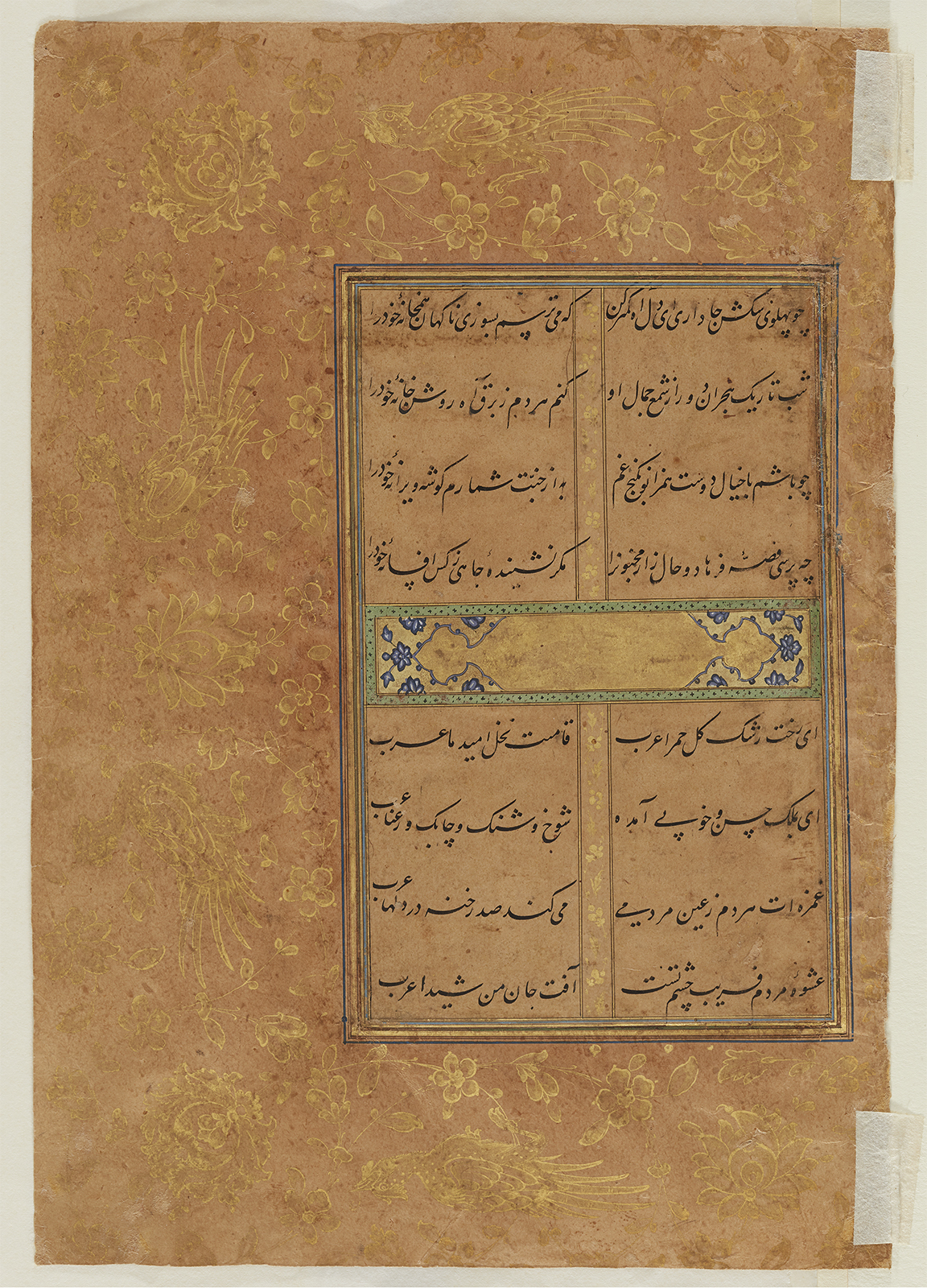

Folio from a manuscript of the Collected Works (Divan) of Sultan Ibrahim Mirza (fol. 19)

- Accession Number:AKM282.19

- Creator:Artist (calligrapher): `Abdullah al-Muzahhib

Artist (painter): `Abdullah al-Muzahhib

Compiled by: Gawhar Shad

Poet: Sultan Ibrahim Mirza, Persian, 1540 - 1577 - Place:Iran, Qazvin

- Dimensions:23.9 cm x 16.8 cm

- Date:1582-83 CE/990 AH

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour, ink, gold and silver on paper

This lovely garden painting is the first illustration in a collection of poetry written by the Safavid prince Sultan Ibrahim, who was both the nephew and son-in-law of the Safavid shah Tahmasp (see AKM282.1). The composition itself belongs to a specific type of scene known by the Persian term bazm, meaning festive court receptions that often took place outdoors and involved music, wine-drinking, and feasting. All the traditional bazm elements are depicted here, beginning with the open garden pavilion, where two figures sit facing each other: one man, bearded and wearing a decorated turban signifying his princely status, offers a small wine cup to his comely younger companion, the drink evidently having been poured from the large golden flask between them. A courtier in the foreground (seemingly propped up against the lower text panel) listens attentively to the pair of musicians playing the daf or tambourine and the stringed sitar, while a kneeling servant offers a golden basin of pomegranates. Still more fruit bowls adorn the terrace, along with a second gold wine flask and basin. Yet another attendant enters from the right; he holds a bucket in one hand, a ewer in the other and what looks like a platter tucked under his arm.[1] The scene’s idyllic setting is complemented by a flowering tree growing between two tall cypresses and by a pair of birds who stare at each other across the treetops.

Further Reading

Notwithstanding the traditional bazm representation here, the poem that the painting accompanies suggests another level of interpretation. Throughout his Divan, Sultan Ibrahim Mirza extols the Prophet Muhammad and other notable figures of Arab origin central to the history of Islam and to Shi’ism, which was the official faith of Iran during the Safavid period. This particular ghazal or amatory ode begins, “O you Arab whose face is the envy of the red rose,” and proceeds through seven verses to praise the Arab’s grace, goodness, stature, and other virtues.

But who exactly is this “Arab?” The answer seems to lie in the city of Mashhad in northeastern Iran, where Sultan Ibrahim Mirza served for some years as governor, and which had long been venerated as the burial place of Imam Reza (d. 818), a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad and the eighth leader of the Shiite branch of Islam. (The name Mashhad means “place of martyrdom.”) Among Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s official responsibilities (see AKM282.1) was to spend time in devotional duties and religious ceremonies, and—of equal relevance for understanding his poetry—to assist the guardian of the Imam Reza shrine in the administration of religious rules and regulations.[2] It seems likely, therefore, that the Arab whom the prince addresses in this ghazal was actually the Imam Reza. The poem hints even further at this devotion to the Iman in a verse about how his gaze penetrates through hundreds of holes in many hearts. Ibrahim Mirza’s own dedication is revealed in the ode’s final couplet, which sounds like a supplication to a saint: “Do not neglect the state of Jahi’s heart/O undaunted, unjust, jovial Arab.”[3]

In such a poetic context, the painting of “princely entertainment” takes on a metaphorical aspect, and Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s amorous language suggests that the motifs here commonly found in bazm scenes—such as the prince offering a wine cup to a beautiful youth—may also be an allegory for a higher or deeper level of platonic love. Indeed, this first Divan painting may hold the key to understanding much of the manuscript’s pictorial program.

— Marianna Shreve Simpson, in collaboration with Chad Kia

Notes

[1] The ewer and platter were originally painted silver, which has oxidized with age.

[2] See Marianna Shreve Simpson, with contributions by Massumeh Farhad, Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s Haft Awrang: A Princely Manuscript from Sixteenth-Century Iran (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997), 228.

[3] Sultan Ibrahim Mirza also appealed to the Iman Reza in a verse written following his removal from the governorship in Mashhad, and appointment to the much less prestigious town of Sabzivar. See Simpson 232.

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.