Click on the image to zoom

Prelude to the Shahnameh (Book of Kings)

- Accession Number:AKM268

- Creator:copied by Mahmud ibn Mahmud ibn Mahmud al-Jamali

- Place:Iran, Shiraz

- Dimensions:33.8 × 24.6 cm

- Date:1457

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour, ink, and gold on paper

This manuscript is a well-known copy of Firdausi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings) produced in Shiraz, Iran. Completed ca. 1010 and dedicated to the Mahmud of Ghazni, then ruler of the region of eastern Iran and today’s Afghanistan, Firdausi’s epic is considered to be one of the world’s longest poems. This copy is composed of 554 pages and 53 illustrations, and it may have been made ca. 1457 for the governor of Shiraz, Pir Bundaq. The colophon, a short inscription which provides details as to a manuscript’s production, indicates that it was copied by the scribe Mahmud al-Jamali in Shiraz. Two centuries later, the manuscript eventually came into the possession of the British Baron Teignmouth (1751–1834), who may have used it to learn Persian.[1]

Further Reading

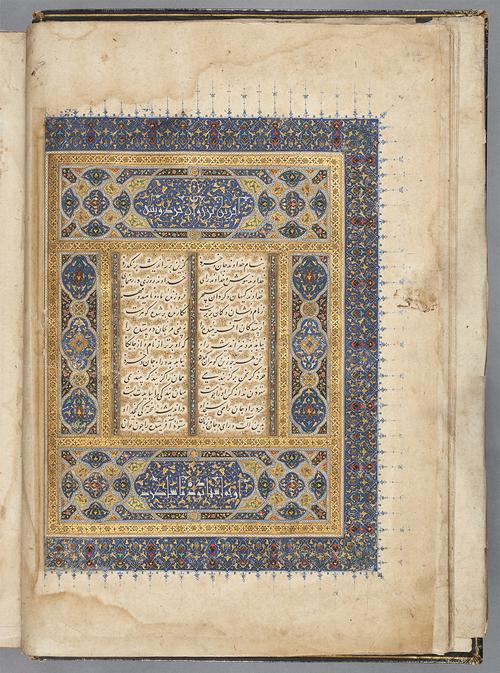

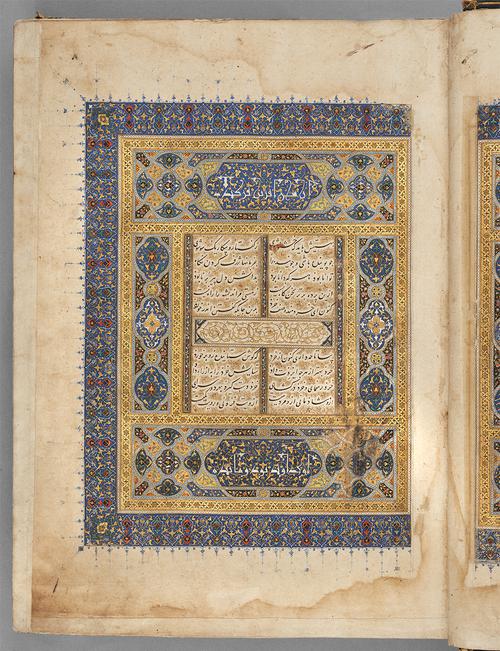

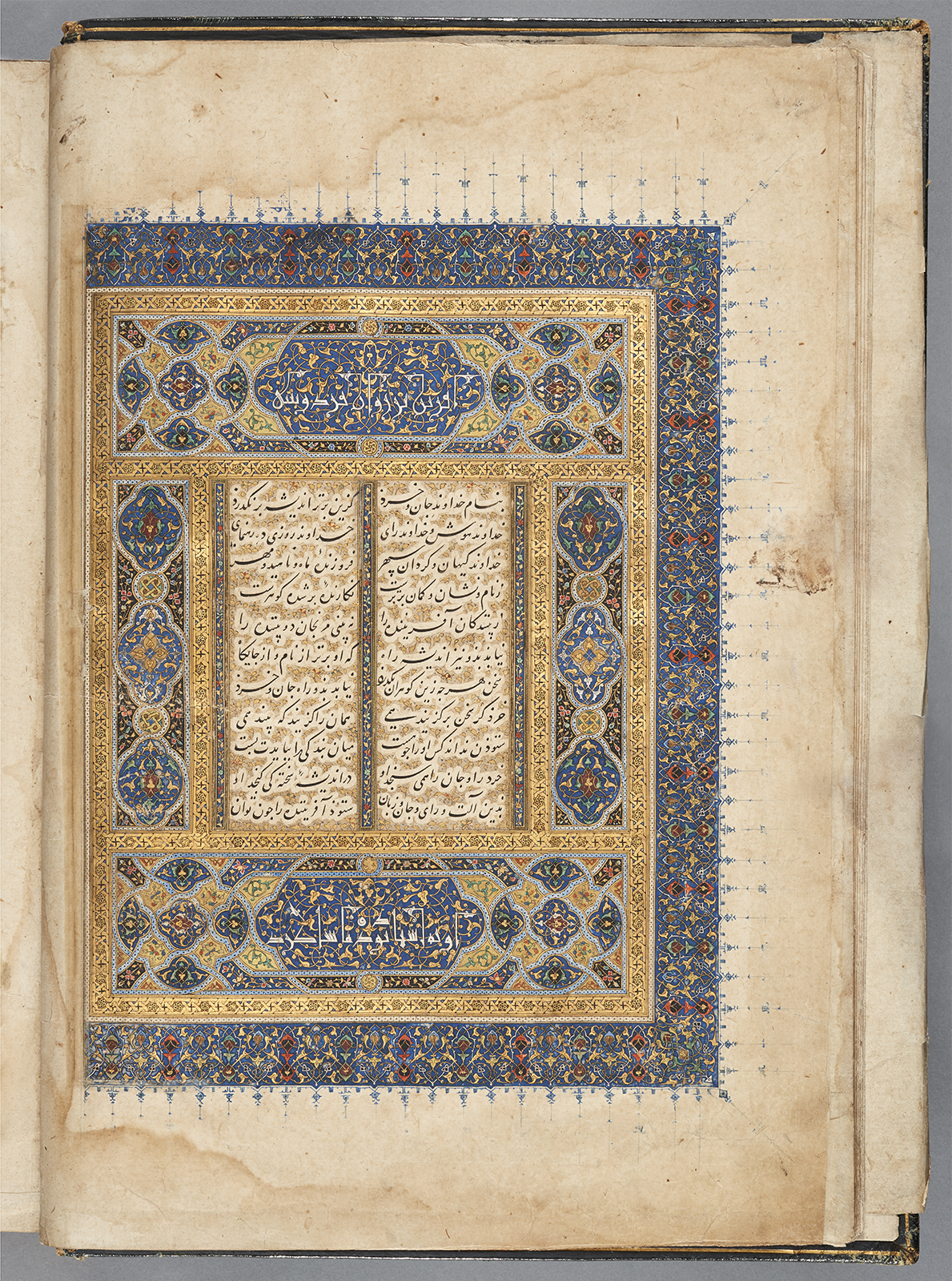

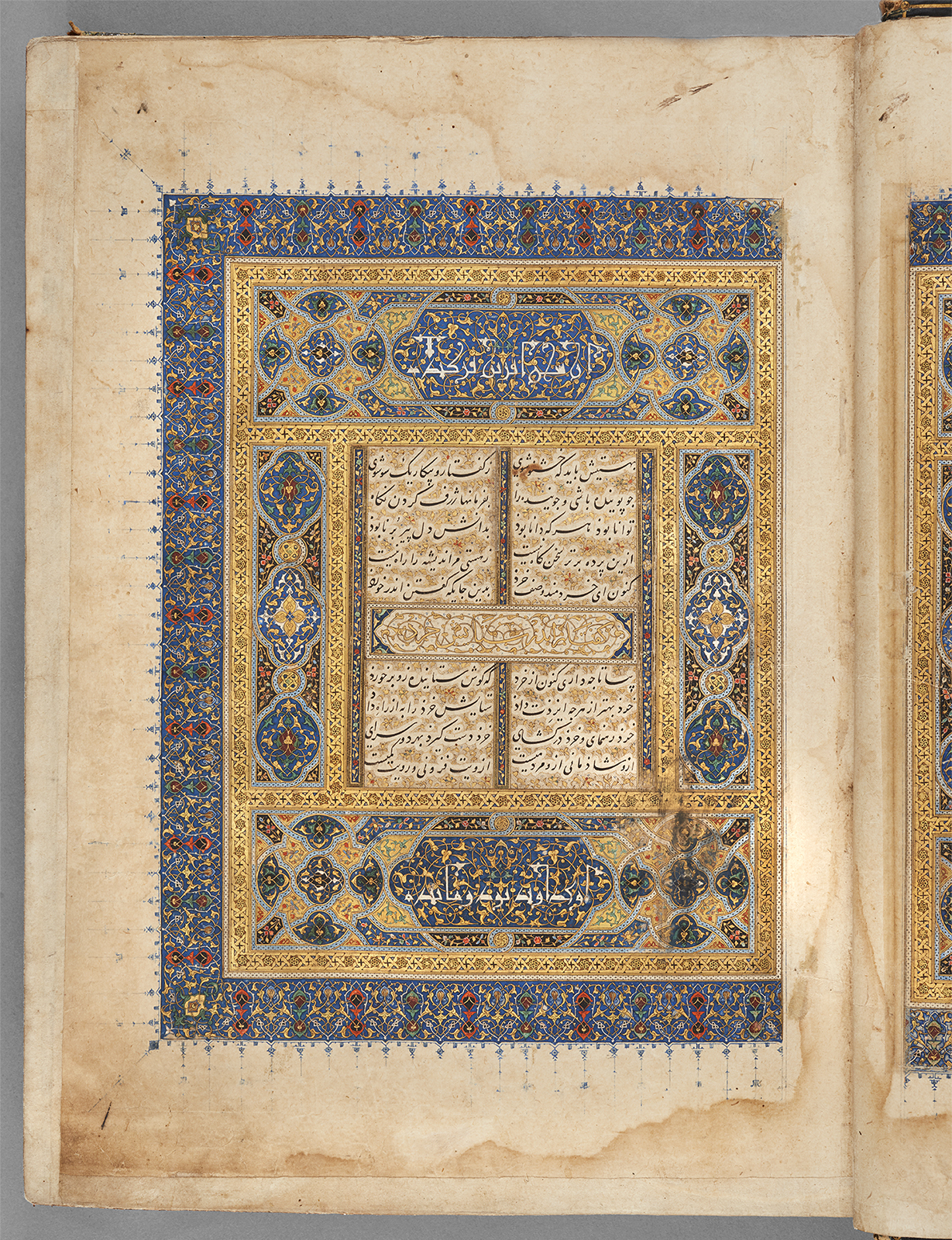

The Shahnameh recounts the epic tales of the kings of Iran from the pre-Islamic period until the Arab conquest in 642 and the adoption of Islam.[2] It begins, however, with a prelude—here presented on an illuminated double page—containing invocations to God and his role in lighting the moon and the planets.[3] This trope was often used in Persian poetry, as the moon was often invoked as the subject of the author’s love and admiration, as well as the conduit of the divine.[4]

Throughout this copy of the Shahnameh, Firdausi’s verse, written in cursive black Nasta‘liq script, is divided into two gold-ruled columns and set beneath a cartouche containing each chapter’s title, written in white Kufic script. The surrounding borders are illuminated with floral scrolls in gold, blue, green, red, and black paint, and separated by gold-edged frames with intricate geometric interlace.

Close studies of the manuscript’s illustrations reveal that a single, unnamed painter completed 50 of the paintings, whereas the remaining three images appear to be the handiwork of two other masters.[5] Several other manuscripts produced in Shiraz are also attributed to the main painter of this manuscript. This indicates that he was a sought-after artist in the city, producing work of a quality appropriate for an elite patron such as the governor Pir Bundaq (1453–60).[6] Although Shiraz was no longer a major capital by the 15th century, it remained an important centre for manuscript production under the patronage of Pir Bundaq and succeeding governors.[7] Moreover, the number of extant 15th-century Shirazi manuscripts—many of them lacking a named patron—suggests that many of these manuscripts were presumably made for commercial circulation.[8]

One of the most striking images from this lavishly decorated Shahnameh illustrates the fall of the mythological Persian ruler Kay Kavus, who is convinced by a devil that the conquest of the heavens was within his reach. Kay Kavus is said to have concocted a plan to raise himself to the heavenly domains by attaching himself to four eagles, who eventually tire and release their grip of the ambitious ruler. The hero Rustam, one of the main protagonists of the poem, is then dispatched to save the fallen king.[9]

This dynamic scene is depicted against a colonnaded pink background, alluding to the interior of court space. Kay Kavus, looking upwards while his flying steeds flail above him, is shown seated in an aerial, canopied chair. Below, Rustam, dressed in a red robe and blue headdress, looks to his right as turbaned onlookers closely observe the king’s skybound progress.[10] The detailed rendering of architectural interiors (complete with golden columns, arched entryways, and floral tile walls) in this scene is repeated throughout the manuscript, testifying to the artist’s mastery of visual depiction.[11]

The rich array of characters—including kings, queens, and mythical creatures—and the great diversity of stories within the approximately 45,000 lines of Firdausi’s verse have enabled the Shahnameh to become one of the most frequently copied, illustrated, and commissioned epics in medieval and early modern Iran. Several copies, both complete or in dispersed folios, are currently held in museums worldwide, including in the Aga Khan Museum Collection (AKM92).

— Michelle al-Ferzly

Notes

[1] Welch and Welch, Arts of the Islamic Book, 57.

[2] Sheila Canby, 2011 The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp. The Persian Book of Kings, p. 11.

[3] Warner and Warner, Shahnama of Firdausi, 100 (with slight changes to the English translation).

[4] Rodinson, La lune, 182–3.

[5] Welch and Welch, Arts of the Islamic Book, 57.

[6] Robinson, Persian Paintings, 28; 106; 148.

[7] Uluç, Turkman Governors, Shiraz artisans, and Ottoman collectors, 65–6.

[8] Ibid., “The Shahnama of Firdawsi as Illustrated Text,” 259–60.

[9] Graves and Benoit, Architecture in Islamic Arts, 194–5.

[10] Ibid.

[11] See Robinson’s discussion of this particular scene in Fifteenth-Century Persian Painting, 16–7.

References

Canby, Sheila. The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp: The Persian Book of Kings. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014. ISBN: 9780300194548

Junod, Benoît, Margaret S Graves, et al. Architecture in Islamic Arts: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2011. ISBN: 9780987846303

Robinson, Basil William. Persian Paintings in the India Office Library. London: Sotheby’s Parke Bernet, 1976. ISBN: 9780856670268

---. Fifteenth-Century Persian Painting: Problems and Issues. New York: New York University Press, 1991. ISBN: 9780814774465

Rodinson, Maxime. “La lune chez les arabes et dans l’Islam.” In La lune: mythes et rites, ed. Philippe Derchain. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1962, 151–215. ISBN: 9782020027762

Uluç, Lâle. Turkman Governors, Shiraz Artisans, and Ottoman Collectors: Sixteenth Century Shiraz Manuscripts. İstanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası, 2006. ISBN: 9789754589634

Warner, Edmond, and Arthur George Warner. Shahnama of Firdausi. London: Degan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1905. ISBN: 9780415865869

Welch, Anthony, and Stuart Cary Welch. Arts of the Islamic Book: The Collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan. Ithaca: Published for the Asia Society by Cornell University Press, 1982. ISBN: 9780801415487

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.