Click on the image to zoom

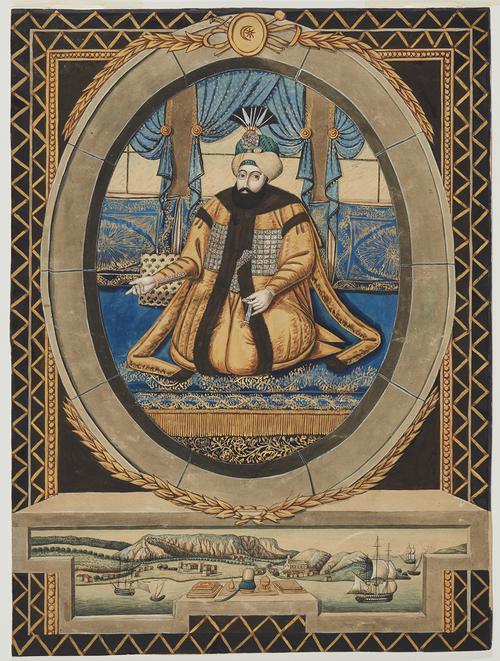

Portrait of Sultan Selim III

- Accession Number:AKM220

- Place:Turkey, Istanbul

- Dimensions:54.1 x 40.5 cm

- Date:ca. 1805

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour and gold on paper

By binding royal Ottoman portraits into albums, individual sultans could insert not merely their image, but also their legacy into a longer lineage of Ottoman imperial power.[1] This portrait of Sultan Selim III (r. 1789–1808) in the Aga Khan Museum Collection depicts the seated ruler at the centre of an oval window wreathed in gold laurels. Beneath this window can be seen a panoramic view of the sea. An arrangement of objects (a Mevlevi Sufi turban; five books that may be Qur’ans; and an incense burner resting upon a stone surface) foregrounds this topographical representation.

Further Reading

In this portrait, the sultan is dressed lavishly. He is wearing a golden cloak lined with black fur in which is tucked a gem-encrusted scabbard. He holds a diamond watch in his left hand, and a gem headpiece fastens a black and grey aigrette to Selim’s green turban. The opulent interior in the background consists of blue and gold curtains, embroidered pillows in the same colour scheme, and a black carpet trimmed with gold fringe.

Sultan Selim III ascended the throne during a tumultuous period, a time when the Ottoman Empire was at war with the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg Empire as well as with Russia.[2] After the signing of peace treaties in the early 1790s, Sultan Selim III ushered in an overhaul of the military, administrative, and economic sectors of his empire, otherwise known as “The New Order” (Nizam-i Cedid).[3] These radical new measures became a key part of Selim’s imperial legacy, as the lower register of the painting affirms. There, a scene of ships at sea and architectural complexes set the foot of a mountain range are depicted. The buildings may perhaps represent new army barracks commissioned by Selim, while the nearby vessels may refer to the Sultan’s interest in international trade.[4]

At the top centre of the oval frame, a small golden medallion encloses a crescent moon with a star nestled in its inner arch. The crescent moon and star emblem became widely used in Ottoman lands during the mid-19th century, as evidenced by standards and banners.[5] Selim III (r. 1789–1807) was the first Ottoman ruler to adopt this symbol in official Ottoman insignia.[6] Moreover, in 1799, he established the Order of the Crescent, which honoured foreigners who distinguished themselves while fighting for the Ottoman Empire.[7] Eventually, the moon and star motif became the national emblem of modern-day Turkey, where it ornaments the country’s national flag.[8]

In the 19th century, official portraits of Ottoman rulers displayed elements of European painting, such as the wreath enveloping the oval frame of the portrait of Selim III, as well as the double fretwork in the background.[9] These particular features can also be seen in a portrait of Suleyman I from the Harvard Art Museums.[10] Like the painting in the Aga Khan Museum Collection, this portrait of Suleyman depicts the sultan seated in a lavish interior within a medallion frame that has been set above a landscape scene of ships at sea.

Selim III also commissioned British artist John Young (1755–1825) to create a collection of prints of Ottoman imperial portraits, A Series of Portraits of the Emperors of Turkey, published in 1815. A number of these later prints closely echo the medallion format of the portrait in the Aga Khan Museum Collection (a format also chosen for a watercolour portrait held in the Victoria and Albert Museum Collection)[11]. In contrast to these portraits, John Young’s portrait series are mezzotints, or coloured prints. The print medium allowed for the wide dissemination of Ottoman imperial portraits abroad as part of 19th-century practices of diplomatic exchange.[12]

— Michelle al-Ferzly

Notes

1. Splendori a Corte, 99; The Path of Princes, 144–45.

2. Shaw, “The Origins of Ottoman Military Reform,” 291.

3. Shaw, 292.

4. Canby, Princes, Poets and Paladins, 103.

5. Sakisian, “Le croissant comme emblème national et religieux en Turquie,” 68–89. See also Ridgeway, “The Origin of the Turkish Crescent,” 241–58.

6. Sakisian, 79. The crescent moon’s official adoption on the Ottoman flag occurs approximately 30 years later, in 1826.

7. Rodinson, La lune, 203.

8. Kurtoğlu, Türk Bayrağı ve Ay Yıldız.

9. Binney, Turkish Miniature Paintings and Manuscripts from the Collection of Edwin Binney III, 114–15; Renda Gunsel, “The Ottoman Empire and Europe,” 16.

10. See Harvard Art Museums, 1985.281, https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/216217?position=15.

11. See Victoria and Albert Museum, SP. 172, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1107263/sultan-selim-iii-stipple-engraving-kapidagli-konstantin/.

12. Roberts, Istanbul Exchanges, 23–24.

References

Binney, Edwin. Turkish Miniature Paintings and Manuscripts from the Collection of Edwin Binney 3rd. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973. ISBN: 9780870990779

Canby, Sheila, et al. Splendori a corte. Arti del mondo islamico dalle collezioni del Museo Aga Khan. Milano: Olivares, 2007. ISBN: 9788885982949

---. Princes, Poets, and Paladins: Islamic and Indian paintings from the collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan. London: British Museum Press, 1999. ISBN: 9780714114835

Gunsel, Renda. “The Ottoman Empire and Europe: Cultural Encounters.” In Cultural Contacts in Building a Universal Civilisation: Islamic Contributions, ed. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu. Istanbul: IRCICA, 2005, 2-24. ISBN: 9789290631446

Junod, Benoît. The Path of Princes: Masterpieces from the Aga Khan Museum Collection. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2008. ISBN: 9789728848484

Kurtoğlu, Fevzi. Türk Bayrağı ve Ay Yıldız. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1938. ISBN: 9789751604781

Orbay, Ayse, ed. The Sultan’s Portrait: Picturing the House of Osman. Istanbul: Isbank, 2000. ISBN: 9789754582192

Ridgeway, William. “The Origins of Turkish Crescent.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 38 (1908): 241–58. DOI: 10.2307/2843299

Roberts, Mary. Istanbul Exchanges: Ottomans, Orientalists, and Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015. ISBN: 9780520280533

Rodinson, Maxime. “La lune chez les arabes et dans l’Islam.” In La lune: mythes et rites, ed. Philippe Derchain. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1962, 151–215. ISBN: 9782020027762

Sakisian, Arménag. “Le Croissant comme emblème national et religieux en Turquie.” Syria. Archéologie, Art et Histoire 22 (1941): 66–80. DOI: 10.3406/syria.1941.4257

Shaw, S. J. “The Origins of Ottoman Military Reform: The Nizam-i Cedid Army of Sultan Selim III.” The Journal of Modern History 37.3 (1965): 291–306. DOI: 10.1086/600691

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.