Click on the image to zoom

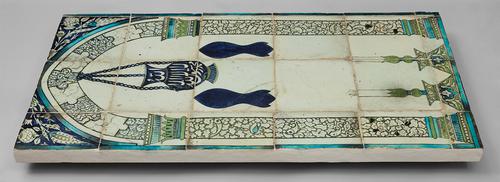

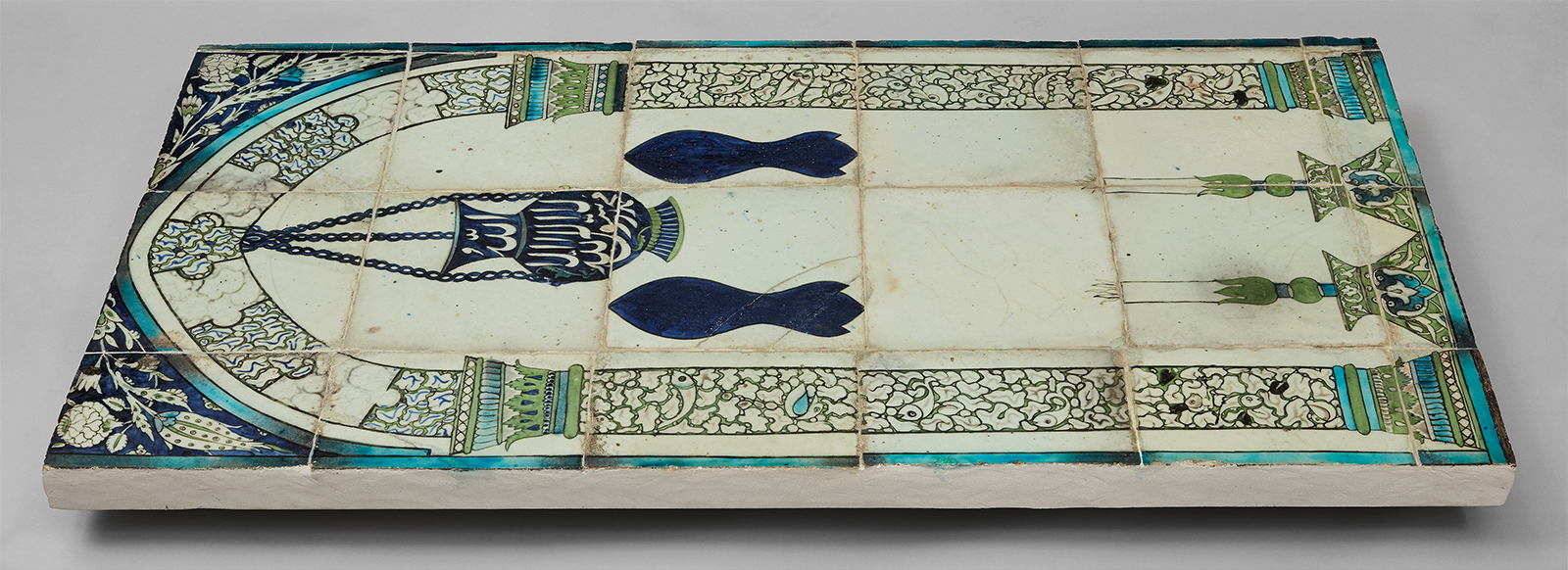

Panel

- Accession Number:AKM585

- Place:Syria, probably Damascus

- Dimensions:123 x 62 cm

- Date:ca. 1575

- Materials and Technique:fritware, underglaze-painted

This panel of 18 tiles belongs to a group of architectural elements known as mihrab panels. Generally, this kind of arched niche was placed in religious buildings, mostly in mosques, where it indicated the direction of prayer on the qibla wall.[1]

Further Reading

Together, the tiles form an arch supported by elaborate green columns. The interior of this arch contains two large flaming candlesticks with two dark blue footprints (referring to the sandals of Prophet Mohammad) above them. In the centre of the arch, a suspended cobalt blue mosque lamp reveals the declaration of the Muslim faith, the shahada. The inclusion of the name Allah at the top of the nozzle is an implicit allusion to the Qur’anic Chapter of Light (Q 24: 35), in which the concept of God is compared to a light shining in a glass lamp hung in a niche. Outside the arch are flower motifs resembling the tulip and carnation sprays of traditional Ottoman art.

This panel in the Aga Khan Museum Collection is closely related to a pair of tile friezes found in a late 16th-century mosque commissioned by the Ottoman governor Darwish Pasha in Damascus. Built in 1574, the mosque is an important example of the impact that Istanbul architecture had on the provinces.[2] The Darwish Pasha panels are located in the courtyard of the mosque and flank the entrance to the prayer hall’s left[3] and right sides.[4] The panel on the left side has no candlestick depictions but rather two lines of Arabic inscriptions between the footprints and lamp. The panel on right side has the candlesticks, footprints, inscriptions, and the lamp with the inscription on it. Like this panel in the Aga Khan Museum Collection, the Darwish Pasha panels bear images of a hanging lamp suspended from the apex of a marble arch by chains. One panel also depicts a pair of lit candles in candlesticks of a similar appearance to those seen here. In addition to the items contained within the arches, similarities in the architectural detailing of the arches on both the Darwish Pasha panels and this piece—joggled voussoirs in alternating colours, slender columns of dappled marble, and ornate acanthus capitals—strongly suggest that all three pieces came from the same workshop. A further tile panel of a different but related type in the Darwish Pasha Mosque has an inscription dating it to 1574–75, and a similar date can probably be assumed for this panel in the Aga Khan Museum Collection.[5]

The Noble Footprints (Qadam sharif) and Noble Sandals (Na’layn sharif) of the Prophet came to be motifs of special reverence, particularly in the 16th century in the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Iran, and India.[6] The shape (mithal) of a pair of stylized sandals like those seen on this panel can be found in sacred and apotropaic contexts from Iran to North Africa, as part of the Ottoman Empire.[7]

In Damascus, the Masjid al-Qadam (Mosque of the Footprint) was originally connected with Moses and later connected to the Prophet Mohammad, showing the common histories of Abrahamic religions.[8] Another example in black stone, now in the oratory of Sitt Ruqayya in Damascus, was transported from Hawran in southern Syria in the 12th century. It is the first mention of a transported footprint, and enabled Damascus to showcase its own relic of the Prophet in the form of a sandal. This tradition seems to have continued until the 19th century, as confirmed by an example in the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. The image may have held particular resonance in the Ottoman Empire.[9]

The hanging lamp, meanwhile, had been associated with the mihrab image since the 12th century or earlier, and the ensemble of a lamp and niche is often implicitly associated with Qur’an 24:35, the so-called Ayat al-nur (Light Verse), which begins, "God is the Light of the heavens and the earth. His light may be compared to a niche that enshrines a lamp." The inscription depicted on the lamp of the present panel is not the Light Verse but a section of the shahada, the Muslim declaration of faith: "There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the Messenger of God." This inscription is relatively unusual on true lamps, but the same formula appears on one of the lamps depicted in the Darwish Pasha tile panels.[10]

The two candlesticks, like the hanging lamp above them, carry spiritual significance—through the metaphor of illumination—when placed in the mihrab image. In this instance, one horizontal line of tiles may have been lost, affecting the appearance of the upper parts of the candles: a comparison with one of the Darwish Pasha panels suggests that the candles may originally have been taller, with more fully defined flames.[11] Perhaps most interesting of all, though, are the little images that have been included within the "marble" of the depicted columns. Close examination reveals hidden fish, ducks, and unidentifiable animals painted into the fictive marble itself, as if petrified within the stone. The painted "marble" borders of some tile panels in the Darwish Pasha Mosque contain similar hidden creatures, and one can only guess at the artist’s motivation for incorporating images of living creatures into tiles specifically designed for a mosque, where such imagery would normally be forbidden. An ancient conception of marble as a "frozen sea" may have informed these designs, as fish predominate here; alternatively, the intention may be to suggest an actual fossiliferous marble,[12] or an association with the Sea of Marmara, which is an inland circular sea of about eight leagues across. The sea earned the name Marmara because from it came all the marble for Constantinople,[13] capital of the Ottoman Empire.

The repertoire of artisans and tile makers was closely related to the royal workshop in Istanbul. Underglaze tiles with an Ottoman decorative vocabulary are the only decorative elements belonging to the imperial style. They are used sparingly on significant parts of the building: the portal, the entrance, and the mihrab walls.[14] The panel in the Aga Khan Museum Collection reflects a dynamic synergy between the imperial vocabulary and local interpretations of the style.

— Filiz Çakır Phillip

Notes

[1] https://www.agakhanmuseum.org/collection/artifact/mihrab-panel-akm585

[2] Darwish Pasha Mosque closely follows the ground plan and support system of Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in Istanbul, built by the chief architect Sinan in the 1560s. See Çiğdem Kafescioğlu, "In the Image of Rum: Ottoman Architectural Patronage in sixteenth-century Aleppo and Damascus," Muqarnas 16 (1999): 90.

[3] https://archnet.org/sites/1830/media_contents/4309

[4] https://archnet.org/sites/1830/media_contents/37444

[5] John Carswell, "Two Tiny Turkish Pots," Islamic Art 2 (1987): 205; Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Architecture in Islamic Arts: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum (Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2011), 78–79; Arthur Millner, Damascus Tiles: Mamluk and Ottoman Architectural Ceramics from Syria (New York: Prestel, 2015), fig. 6.2, p. 245.

[6] Perween Hasan, "The Footprint of the Prophet," Muqarnas 10 (1993): 335–36; Belgin Demirsar Arlı, "Depictions of ‘Nalin-i Serif’ on Ottoman Tiles," 14th International Congress of Turkish Art, Paris, Collège de France, 19-21 September 2011 (Paris: Collège de France, 2013), 273–82. Another panel is in the collection of Shangri-La Islamic Art Cultural Center of Doris Duke Foundation in Honolulu (http://www.shangrilahawaii.org/islamic-art-collection/search-the-collection/?id=3763) following the same design repertoire but dating much later, from the 17th century. Therefore, Belgin Demirsar Arlı suggests they are all produced in the same workshop in Damascus, which can be argued only for the two panels in Darwish Pasha Mosques and the Aga Khan Museum’s panel. See Belgin Demirsar Arlı, 280-81; 276.

[7] Dalu Jones, Qallaline Tile Panels: Pictures in North Africa (London: Art and Archaeology Research Papers, 1978), 16.

[8] Perween Hasan, 335.

[9] Christiane Gruber, "A Pious Cue-All: The Ottoman illustrated prayer Manual in the Lilly Library," The Islamic Manuscript Tradition: Ten centuries of Book Arts in Indiana University Collections (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2009), 136–37.

[10] See Architecture in Islamic Arts, no. 12, 78–79.

[11] See Sophie Makariou, ed., Chefs-d'oeuvre islamiques de l'Aga Khan museum: accompagne l'exposition organisée a Paris, Musée du Louvre, du 5 octobre 2007 au 7 janvier 2008 (Milan; Paris: 2007), no. 72, 200–1; The Path of Princes: Masterpieces from the Aga Khan Museum Collection (Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2008), no. 18, 76–77.

[12] The theories of geology promulgated by Aristotle and Theophrastus. They had thought that marbles were deposits of purified earthy matter suspended in water that percolated down through the earth’s crust to deep reservoirs, where the whole brew was frozen or fired solid by earthly humours. During the medieval period these geologic perceptions were accepted by Arab science in the East. Cf. Barry Fabio, "Walking on Water: Cosmic Floors in Antiquity and the Middle Ages," The Art Bulletin 89.4 (2007): 630–31. For the marble in written sources from the 9th to 15th centuries, Marcus Milwright gives an informative introduction. See Marcus Milwright, "Waves of the Sea: Responses to Marble in Written Sources," The Iconography of Islamic Art, 211–21.

[13] Further references by Fabio 2007, 651.

[14] See Kafescioğlu, 91.

References

Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Architecture in Islamic Arts: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2011. ISBN: 9780987846303

---. The Path of Princes: Masterpieces from the Aga Khan Museum Collection. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2008. ISBN: 9789728848484

Carswell, John. "Two Tiny Turkish Pots," Islamic Art 2 (1987): 203–16. ISBN: 9780870991110

Demirsar Arlı, Belgin. "Depictions of ‘Nalin-i Serif’ on Ottoman Tiles," 14th International Congress of Turkish Art, Paris, Collège de France, 19-21 September 2011. Paris: Collège de France, 2013, 273-82. ISBN: 9789751736970

Fabio, Barry. "Walking on Water: Cosmic Floors in Antiquity and the Middle Ages," The Art Bulletin 89.4 (2007): 627–56. DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2007.10786367

Gruber, Christiane. "A Pious Cue-All: The Ottoman illustrated prayer Manual in the Lilly Library," The Islamic Manuscript Tradition: Ten centuries of Book Arts in Indiana University Collections. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2009, 117–53. ISBN: 9780253353771

Hasan, Perween. "The Footprint of the Prophet," Muqarnas 10 (1993): 335–43. DOI: 10.2307/1523198

Jones, Dalu. Qallaline Tile Panels: Pictures in North Africa. London: Art and Archaeology Research Papers, 1978. ISBN: 9780906468012

Kafescioğlu, Çiğdem. "In the Image of Rum: Ottoman Architectural Patronage in sixteenth-century Aleppo and Damascus," Muqarnas 16 (1999): 70–96. DOI: 10.2307/1523266

Makariou, Sophie, ed. Chefs-d'oeuvre islamiques de l'Aga Khan museum: accompagne l'exposition organisée a Paris, Musée du Louvre, du 5 octobre 2007 au 7 janvier 2008. Milan; Paris: 2007. ISBN: 9782350311326

Millner, Arthur. Damascus Tiles: Mamluk and Ottoman Architectural Ceramics from Syria. New York: Prestel, 2015. ISBN: 9783791381473

Milwright, Marcus. "Waves of the Sea: Responses to Marble in Written Sources," The Iconography of Islamic Art, 211–21. ISBN: 9780748633678

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.