Click on the image to zoom

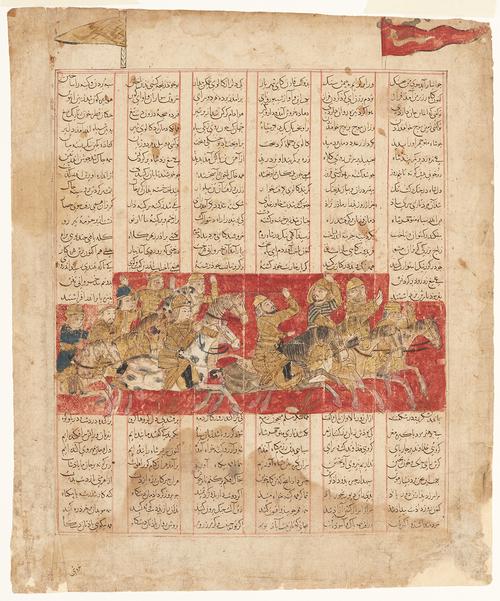

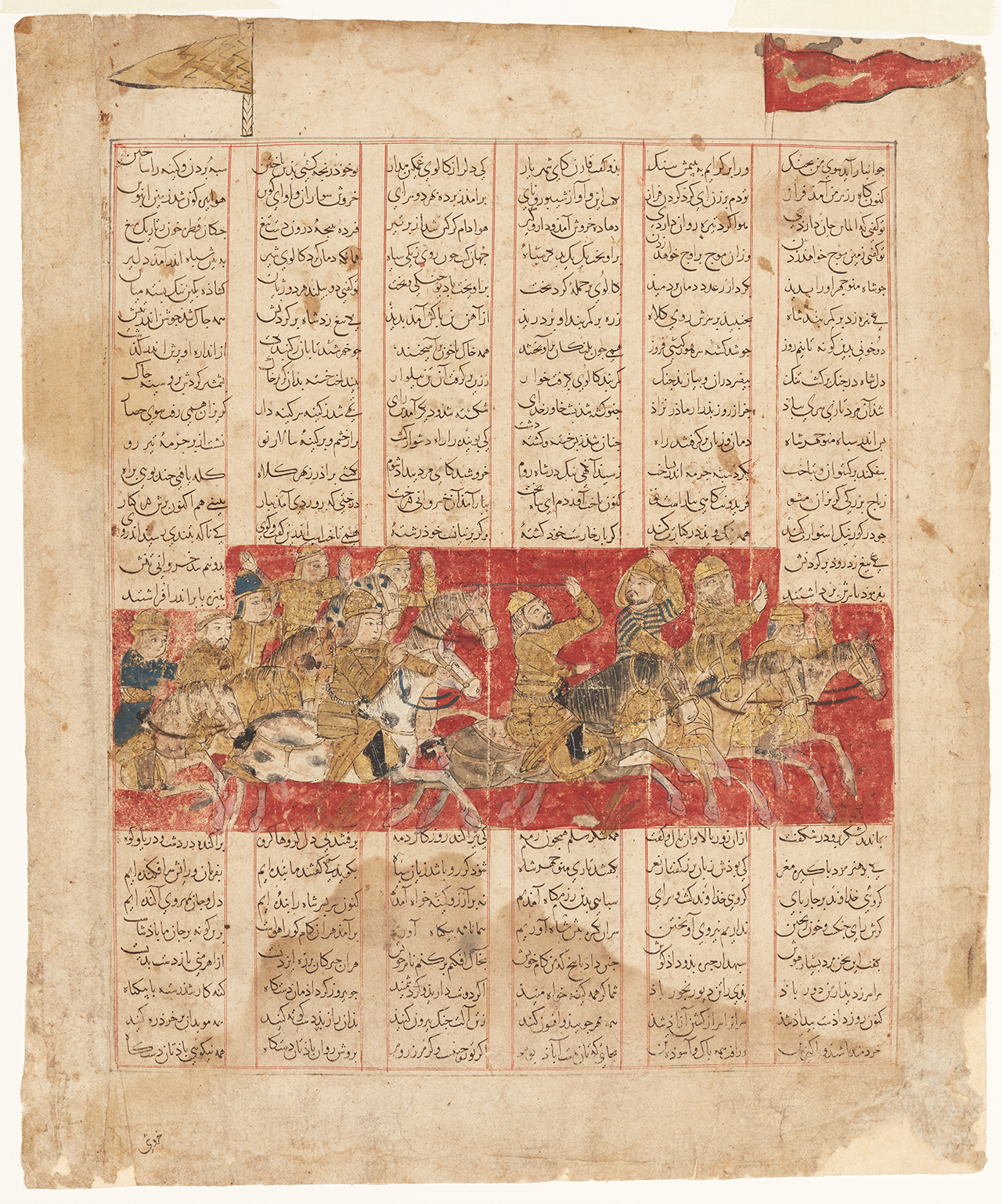

Manuchihr and Qaran fight Salm

Folio from a dispersed copy of Firdausi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings)

- Accession Number:AKM28

- Place:Iran, Shiraz

- Dimensions:36.5 x 30 cm

- Date:741 AH /1341

- Materials and Technique:Ink, coloured pigments and gold on paper

This folio AKM28 (folio 19 verso) is from one of the earliest known illustrated copies of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), an epic poem by Firdausi (c. 935–1020) that recounts the story of Iran from mythical times through to the arrival of the Muslim Arabs in the 7th century AD. The battle scene it depicts is one of possibly 140 paintings from a heavily illustrated Shahnameh that was copied and painted in 1341 in Shiraz, a city then governed by Inju administrators on behalf of Iran’s ruling Ilkhanid or Mongol dynasty (1256–1353).

Further Reading

Firdausi’s poem spans the reign of 50 monarchs and three temporal eras—the mythical, legendary, and historical. This particular folio (19b) comes from an early section of the epic poem in which the poet Firdausi recounts the tales of the kings who ruled during Iran’s mythical Pishdadian dynasty. The great ruler Faridun ascended the Pishdadian throne after overthrowing an evil despot and rescuing the Iranian people from tyranny. Having ruled wisely for 500 years, Faridun divided his realm among his three sons: the eldest, Salm, is given the western part of the kingdom; the middle son, Tur, acquires Turan (Central Asia) and China; and the youngest, Iraj, receives Iran, along with Faridun’s throne. The older two brothers grow jealous of Iraj and kill him. This murder marks the beginning of the enmity and warfare between Iran and Turan that would dominate the second, legendary era recounted in Firdausi’s Shahnameh.

After Iraj’s death, his wife gave birth to a daughter who in her turn had a splendid son named Manuchihr. The boy was raised by Faridun (his great-grandfather), who taught him the arts of both kingship and warfare. Salm and Tur soon learn of Manuchihr and, realizing the threat he posed to their security, decided to try to make peace with their father Faridun and to apologize for having killed Iraj. Faridun rejects his sons’ advances, and instead dispatches Manuchihr, accompanied by a valiant Iranian commander named Qaran, with a large army to avenge Iraj’s murder.

Salm and Tur gather their forces, but they are no match for the Iranian troops led by Manuchihr and Qaran. During a fierce nighttime battle, Manuchihr kills Tur. After still more fighting Salm realizes the precariousness of his situation and flees the battlefield in desperation. Manuchihr follows his great-uncle Salm in hot pursuit. Drawing level with Salm, Manuchihr raises his sword and splits Salm’s body in two. He then sends Salm’s severed head to Faridun with a letter describing the battles and the strategies used to overthrow his grandfather’s murderers. In thanks for this victory, Faridun has Manuchihr crowned king of Iran.

The composition illustrating this momentous Shahnameh episode is rendered as a crowded battle scene, with ten mounted warriors charging across an open plain. The nearby verses tell us that Manuchihr rides a white horse; thus he may be the combatant mounted on the white and black-dappled steed in the picture. Qaran may be the bearded rider in front raising a blue stick. Alternatively, this figure could be Salm trying to whip his horse forward to escape Manuchihr’s wrath. In either case, the illustration represents the moment when Manuchihr catches up to Salm and is about to kill him.

Like many of the illustrations in the 1341 Shahnameh, this folio has a red background, possibly indicating that the artist is following older traditions of mural painting in Iran and Central Asia. Similar to other illustrations from this volume, it also depicts soldiers whose hands do not seem to be holding their horses’ reins. As well, two warriors hold their hands upwards as if holding banners or standards, though no shafts are depicted. One banner, decorated with a dragon, flies above in the upper right margin. Another flag with a zig-zag design appears at the upper left, perhaps being “held” by the rider raising his hands beneath the left column divider.

Introduction to the 1341 Shahnameh

The 1341 Shahnameh originally contained the entire Book of Kings by poet Abu’l-Qasim Firdausi (c. 935-1020). Completed in 1010, Firdausi’s epic poem recounts the story of Iran from mythical times through to the arrival of the Muslim Arabs in the 7th century AD. It spans three temporal eras—the mythical, legendary, and historical—and the reign of 50 monarchs, containing some 50–60,000 verses. Firdausi’s Shahnameh has been a vital source of artistic inspiration in Iran and other Persianate cultures for centuries, continuing into the modern era.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of illustrated copies of the Shahnameh survive today in public and private collections worldwide. Among the earliest known of these numerous copies is a richly decorated and illustrated volume dated 741 hijra, corresponding to 1341 AD (AKM 28, AKM29, AKM30, AKM31, AKM32, AKM33, AKM34, AKM35, AKM36, AKM37 and AKM88). The 1341 Shahnameh, as the manuscript is now generally called, was commissioned by a certain Qiwam al-Dawla wa’l-Din Hasan, who served as vizier, or minister, to the governor of Fars province in south-central Iran. Although at that time the entire country of Iran, along with neighbouring lands, was ruled by the Mongol dynasty of the Ilkhanids, individual regions, such as Fars, were governed by native Iranian administrators (Injus). That Qawam al-Daula was the patron of the 1341 Shahnameh is afiirmed by a pair of facing folios illuminated, or decorated, with large rosettes, which appear at the start of Firdausi’s poetic text and which are inscribed with a long dedication, specifying that the manuscript was made by order of Qiwam al-Dawla’s kitabkhana, or library, at the end of the auspicious month of Ramadan in the year 741 (corresponding to mid-March 1341) and hailing him as “the great lord, honorable minister, chief vizier of glorious Fars.” [1] The 1341 Shahnameh also has a colophon, or scribal note, on its last surviving folio, belonging to the Aga Khan Museum (AKM37v), which provides the name of the manuscript’s copyist: Hasan ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Ali ibn Husaini, known as al-Mausili.

In its original form, the 1341 Shahnameh would have contained approximately 325 folios, of which well over one-half is extant and found in museums and libraries worldwide. The known leaves, including eleven in the Aga Khan Museum Collection, consist of medium-weight paper, dark cream or light beige in colour and unpolished. Most are quite worn and stained with age and many have been trimmed from their original size. The standard page contains thirty lines of text written in six columns, with three Shahnameh verses per line. Based on the folios surviving today, we know that the 1341 Shahnameh originally contained at least 108 paintings and possibly as many as 140, making it the most heavily illustrated volume of the epic produced in Injuid Shiraz.

In general, the illustrations in the 1341 Shahnameh follow the stylistic conventions associated with painting in Shiraz during the Inju period, including a rather limited palette of black, white, red, blue, yellow and ochre pigments and a loose, seemingly careless, application of these colours in thin washes, especially for the backgrounds. Gold is also used to highlight costumes, armour and horse trappings. The faces of male characters come in two standardized facial types: round faces without beards and long faces with pointed, black beards. (But note that in some instances the beards have been repainted.) Landscapes usually lack any ground plane; at most terra firma is indicated by clumps of grass.

While it has been possible to reconstruct the manuscript’s textual and artistic contents, its history following its transcription in 1341 by the scribe Hasan ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Ali ibn Husaini for the Inju vizier Hajji Qiwam al-Dawla wa’l-Din Hasan remains speculative. The folios in the Aga Khan Museum formerly belonged to the important collection of Persian manuscripts and paintings formed by Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan in Geneva.

— Marianna Shreve Simpson

Notes

[1] These dedication folios belong today to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., S1986.110 verso and S1986.111, recto.

References

Simpson, Marianna Shreve. “A Reconstruction and Preliminary Account of the 1341 Shahnama, With Some Further Thoughts on Early Shahnama Illustration,” in Persian Painting from the Mongols to the Qajars, Robert Hillenbrand, ed. London and New York: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 2000, 217–47. ISBN: 9781850436591

Sims, Eleanor. “Thoughts on a Shahnama Legacy of the Fourteenth Century: Four Inju Manuscripts and the Great Mongol Shahnama,” in Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan, Linda Komaroff, ed. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006, 269–85. ISBN: 9789004150836

Wright, Elaine. “Patronage of the Arts of the Book Under the Injuids of Shiraz,” in Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan, Linda Komaroff, ed. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006, 248–268. ISBN: 9789004150836

Wright, Elaine. The Look of the Book: Manuscript Production in Shiraz, 1303-1452. Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, in association with the University of Washington Press and the Chester Beatty Library, 2012. ISBN: 9780295991917

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.