Click on the image to zoom

Album Page

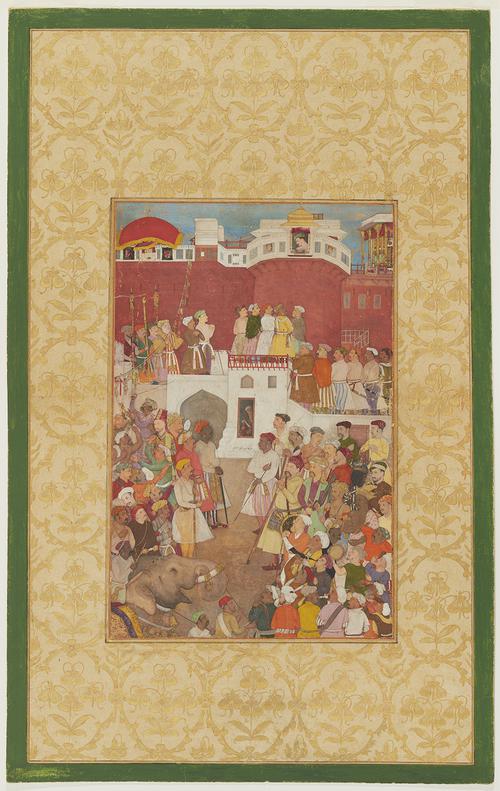

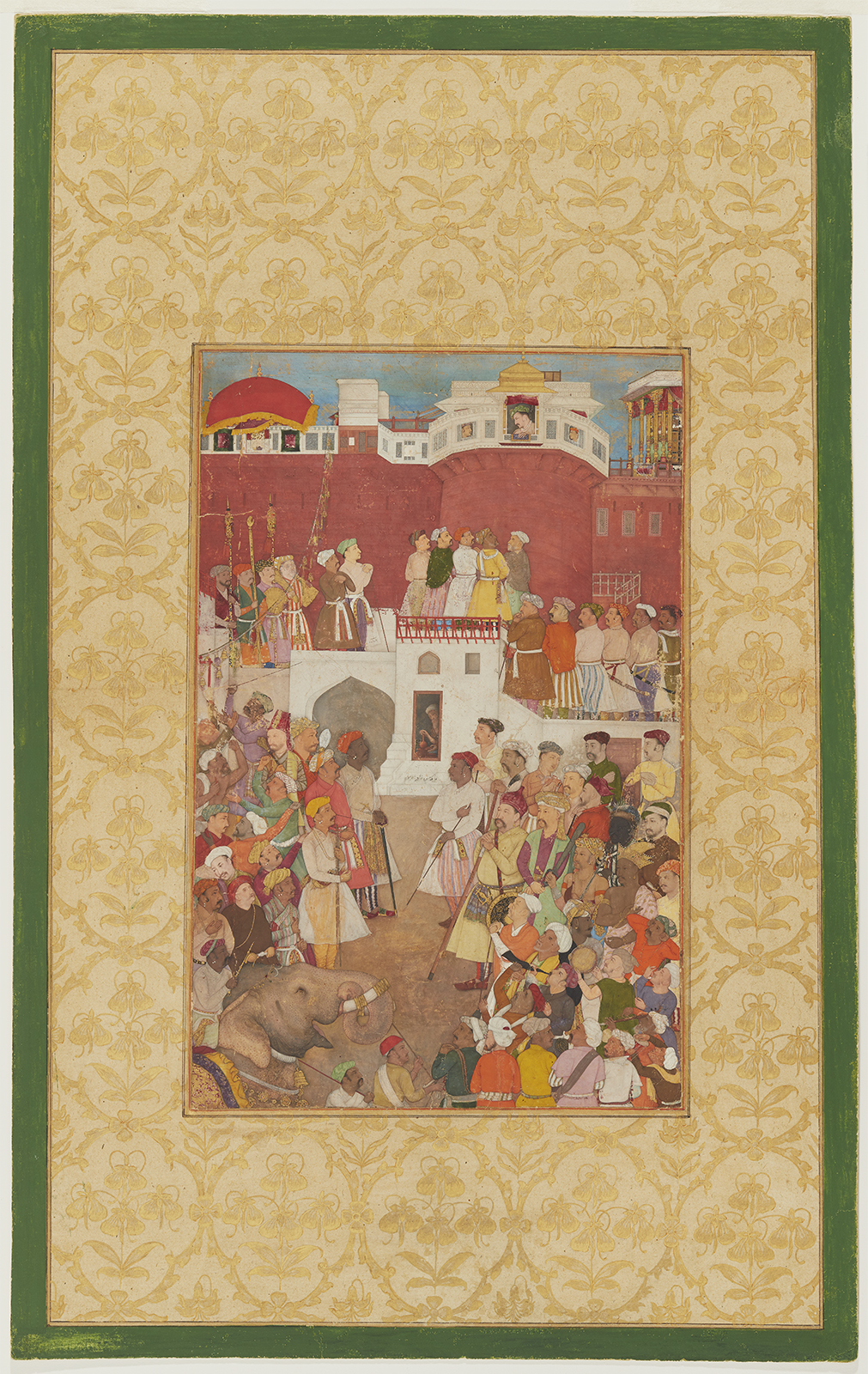

Front, Emperor Jahangir at the jharoka window

Back, Calligraphy

- Accession Number:AKM136

- Creator:calligraphy attributed to Muhammad Husayn al-Kashmiri (“Zarin Qalam”)

- Place:India

- Dimensions:56 x 35.2 cm

- Date:late 16th – early 17th centuries

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour, ink, and gold on paper

This double-sided page, intended for an album, is likely the product of two masters: Abu‘l-Hasan, one of the most famous artists of the Mughal court, and Muhammad Husayn al-Kashmiri, honoured by the emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605) with the title of Zarin Qalam (Golden Pen). [1]

Further Reading

The painting depicts Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–27) in a balcony window (called a jharoka) and looking down to Agra Fort. His top-ranking officials stand on the marble terrace just below him. Beneath the terrace, lower-ranking officials and the public gather in a courtyard. Near the red canopy at the left is suspended a golden chain with golden bells. In his Tuzuk-I Jahangiri (Memoirs of Jahangir), the emperor speaks of this golden chain as a “chain of justice”:

After my accession, the first order that I gave was for the fastening

up of the chain of justice, so that if those engaged in the administration

of justice should delay or practice hypocrisy in the matter of those

seeking justice, the oppressed might come to this chain and shake it so

that its noise might attract attention. Its fashion was this: I ordered them to

make a chain of pure gold[.]

The first British ambassador to the Mughal court, Sir Thomas Roe (ca. 1581–1644), wrote about the imperial tradition of darshan, which this painting vividly portrays. He also describes how petitioners could use the chain of justice to attract the emperor’s attention if his decision was not to their satisfaction. Though darshan was originally a Hindu religio-political ritual, it became a decidedly theatrical event for Jahangir.

Such theatricality is expressed well in this painting. Here, men of high rank—grandees of the empire—stand in hierarchical order, in an appropriate degree of proximity to the emperor. Most of them are identified through minute inscriptions that give their names, either on collars or girdles. The scene below them is not orderly but infinitely more colourful; commoners of every conceivable type and station have gathered. Hindus and Muslims, Turks and Afghans, Iranians and Abyssinians from Horn of Africa. It is clear that the artist is presenting a microcosmic view of the great diversity of India in this painting. Interestingly, these commoners do not have easy access to Jahangir’s chain of justice: it is guarded, and a prospective petitioner is shown being beaten away. [2]

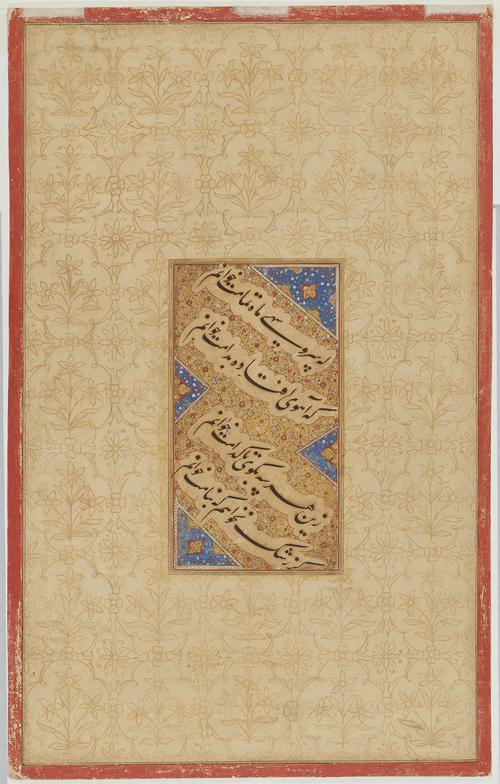

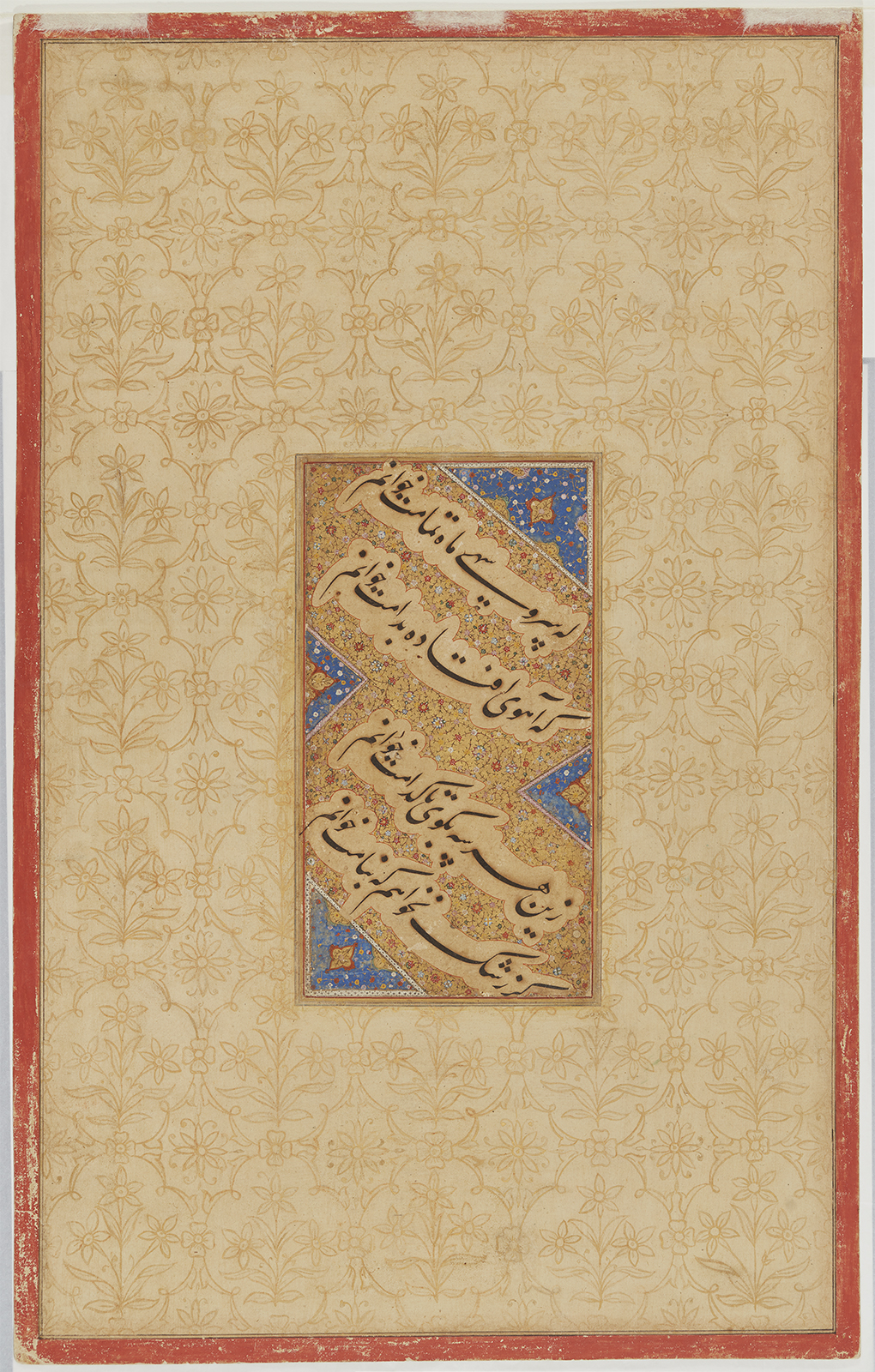

On the reverse side of this page, four lines of a poem by the Iranian mystical poet ‘Ayn al-Qadat Hamadani (d. 1131) are rendered in fine nasta‘liq calligraphy. In them, the speaker confesses a desire to guard his beloved’s identity from the rest of the world:

Sometimes I call you cypress, sometimes moon,

And sometimes musk deer, fallen in the snare.

Now tell me, friend, which one do you prefer?

For out of jealousy, I’ll hide your name! [3]

The exemplary skill with which the calligraphy has been executed leads Anthony Welch to conclude it is the product of Muhammad Husayn al-Kashmiri. One of the greatest calligraphers at the court of Mughal rulers, he is specifically mentioned in A’in-i Akbari (Institutes of Akbar) as a calligrapher who excelled in nasta‘liq script. [4]

— Filiz Cakir Phillip

Notes

[1] See Anthony Welch and Stuart Cary Welch, Arts of the Islamic Book: The Collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1982), 212.

[2] See also BN Goswamy, The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 101 Great Works, 1100-1900 (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2014), 331–33.

[3] Abu’l Fazl ibn Mubarak, Ayeen Akbery: Or, The Institutes of the Emperor Akber, Vol. 1. Trans. Francis Gladwin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 112.

[4] Welch and Welch, 212.

References

Canby, Sheila. Princes, Poets & Paladins: Islamic and Indian Paintings from the Collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan. London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1998. ISBN: 9780714114835

Goswamy, BN. The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 101 Great Works, 1100-1900. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN: 9780500239506

Gruber, Christiane, ed. The Moon: A Voyage Through Time. Toronto: Aga Khan Museum, 2019. ISBN: 9781926473154

Mubarak, Abu’l Fazl ibn. Ayeen Akbery: Or, The Institutes of the Emperor Akber, Vol. 1, Trans. Francis Gladwin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN: 9781108067003

Welch, Anthony, and Stuart Cary Welch. Arts of the Islamic Book: The Collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1982. ISBN: 9780801415487

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.