Click on the image to zoom

Folio from the manuscript of the Spiritual Words from Greek Philosophy with Sayings of the Philosophers Accompanied with their Portraits

Al-Kalimat al-Ruhaniyya min al-Hikam al-Yunaniyya fi Kalimat al-Hukama’ wa Ashkalihim

- Accession Number:AKM283.f41v

- Creator:Artist (calligrapher attributed): Yaqut Al-Musta'simi, died 1298

Artist (painter attributed): Mahmud b. Abi'l-Mahasin Al-Qashi - Place:Iraq, Baghdad

- Dimensions:21.2 cm x 15.7 cm x 1.3 cm

- Date:late 13th Century/additions made 1899

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour, ink, and gold on paper

This manuscript of Al-Kalimat al-Ruhaniyya min al-Hikam al-Yunaniyya fi Kalimat al-hukama’ wa Ashkalihim (Spiritual Words from Greek Philosophy with Sayings of the Philosophers Accompanied with their Portraits) presents collected maxims in Arabic attributed to Greek philosophers and notables. The volume with its illuminated heading (fol. 1r) and 13 textual illustrations can be attributed to late 13th-century Baghdad. Its colophon (fol. 46r) is signed with the name of the celebrated Abbasid/Ilkhanid calligrapher Yaqut al-Musta‘simi (d. 1298), as well as an artist named Mahmud b. Abi al-Mahasin al-Qashi, who specifies that he illustrated (ṣawwarahu) the book.[1] It has 46 folios[2] written in naskh script and the manuscript was rebound some time between the 16th and 18th centuries, possibly in the Ottoman world.[3] At least six copies of this same text—two closely related to AKM283—are found in the Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul.[4]

See AKM283 for more information about the manuscript and links to the other illustrations.

Further Reading

Although no other works illustrated by Mahmud b. Abi al-Mahasin al-Qashi are known, a large number are signed by the scribe Yaqut al-Musta‘simi. Yaqut was greatly admired in the Turko-Persian world, and any piece of calligraphy bearing his name was avidly collected. His works were the primary models chosen to be duplicated for centuries, and especially during the Timurid period, when even the Timurid prince Ibrahim Sultan is believed to have replicated his work. [5] Furthermore, his calligraphic pieces had an enormous material value, as is demonstrated by a letter preserved in the munsha’at (a collection of examples of mostly epistolary and some literary texts) of the Ottoman bureaucrat and poet Mesihi (d. after 1512). In the letter Mesihi writes that he is sending a formerly requested calligraphic specimen (mashq) of Yaqut al-Musta‘simi to an unknown recipient. He adds that even if a person just brought the news of the existence of such a piece, he would deserve to be given a gift of more than 10,000 akçes, but the value of the work itself would be more than one thousand gold pieces.[6] Yaqut’s fame, and possibly the high demand for any piece of calligraphy bearing his name, caused his works to be copied and often duplicated together with his signature, as a result of which the penmanship of the works signed with the name Yaqut remains at times questionable. Therefore, when a colophon is signed with this name, both the possibility of its scribe being Yaqut al-Musta‘simi himself, and the possibility of it being a duplication are always considered. [7]

The tradition of collecting maxims in Arabic attributed to various personages stretches back at least to the Abbasid period.[8] When defining the obligations of a secretary (dabir) as one of the four principal advisers of a ruler, the Ghurid court poet Nizami ‘Aruzi Samarqandi lists Arabic maxims (amthal-i ‘Arab) and Persian sayings (kalimat-i ‘Ajam) among the texts he must accustom himself to study in his book Chahar Maqala (The Four Discourses) of ca. 551 (1156).[9] Besides collecting these texts, the Abbasid caliphs also initiated a concerted effort to translate and collect works by Greek philosophers. The seventh caliph al-Ma’mun (r. 813–33), for example, founded an institution called the Bayt al-Hikma (“House of Wisdom”) in Baghdad specifically for the translation of philosophical and scientific works from Greek originals brought from “the country of Rum.”[10] Maxims attributed to Greek philosophers were also collected within volumes of maxims attributed to sages from Muslim societies.

Together, these texts belong to the genre of advice/didactic literature, and they were found in courtly libraries throughout the Islamic world. Thomas Lentz has convincingly shown that one in particular was prepared for the Timurid prince Baysunghur (d. 1434),[11] while the rich holdings of Istanbul libraries include a number of such codices, some of which are signed with the name of Yaqut al-Musta‘simi or one of his six celebrated students. The Süleymaniye Library, in particular, has several, [12] and some may have been listed by Bayezid’s librarian Atufi in a 1503–4 inventory of the holdings of the sultan’s library.[13]

Besides such collections produced as codices, maxims attributed to Greek philosophers were also found among those that were written in scrolls in the 13th and 14th centuries. These Ilkhanid scrolls were then mostly cut up and preserved in albums. While early Timurid albums, such as the Calligraphy Album of Baysunghur (Topkapı Palace Museum Library H. 2310) [14] from the 1430s, have intact pieces of such scrolls, they must have become much rarer as time went by. Even tiny fragments of these scrolls, at times bearing only fragments of maxims, became collectible pieces and were carefully preserved in the later albums.

Examples of maxims in Arabic reputedly written by Aristotle to Iskandar are found in several Istanbul albums as well. One of the Fatih or Yaqub Beg Albums from the Topkapı Palace Museum Library has two instances (H. 2153, fols. 122a and 173a), while the Baba Nakkaş Album from the Istanbul University Library has a scroll that was written by the Timurid prince Ibrahim Sultan (d. 1435), which includes them (F. 1423, fol. 12b). Both these albums are thought to have been compiled during the late 15th century, or at the latest by 1512. The Tahmasp Album from the Istanbul University Library, compiled around 1558, also has two instances of maxims in Arabic attributed to Iskandar (F. 1422, fols. 49a, 61b).

Both the illuminated heading and the 13 illustrations of the AKM283 are similar to those from surviving decorated manuscripts from the late 13th century attributed to the area covering Mesopotamia, northern Iraq, and southeastern Anatolia. Stylistic characteristics—such as their approach to figural representation, treatment of landscape elements, and frameless positioning of those features against a blank background directly on the page—adhere to the shared medieval pictorial repertoire of the region. Manuscripts with illustrations sharing the same idiom are found in various collections in the world. [15] The most significant one is a copy of the Marzubannama of Sa‘d al-Din al Varavini preserved in Istanbul (Archaeology Museum Library ms. 216) with a colophon (fol. 48) dated 10 Ramadan 698 (May 1299) specifying that it was completed “in the eastern district of Baghdad.”[16]

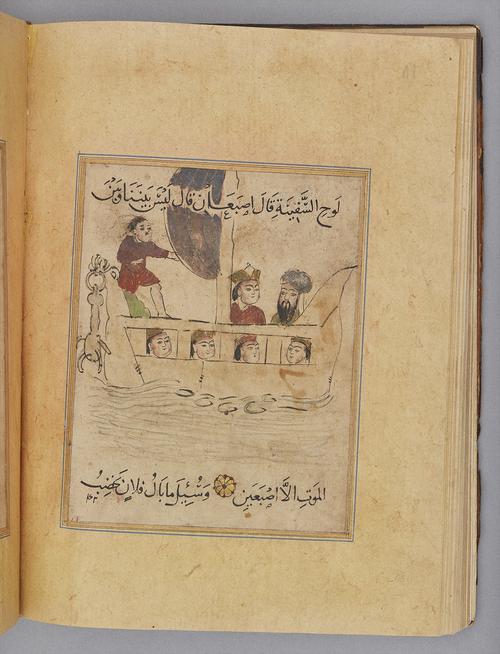

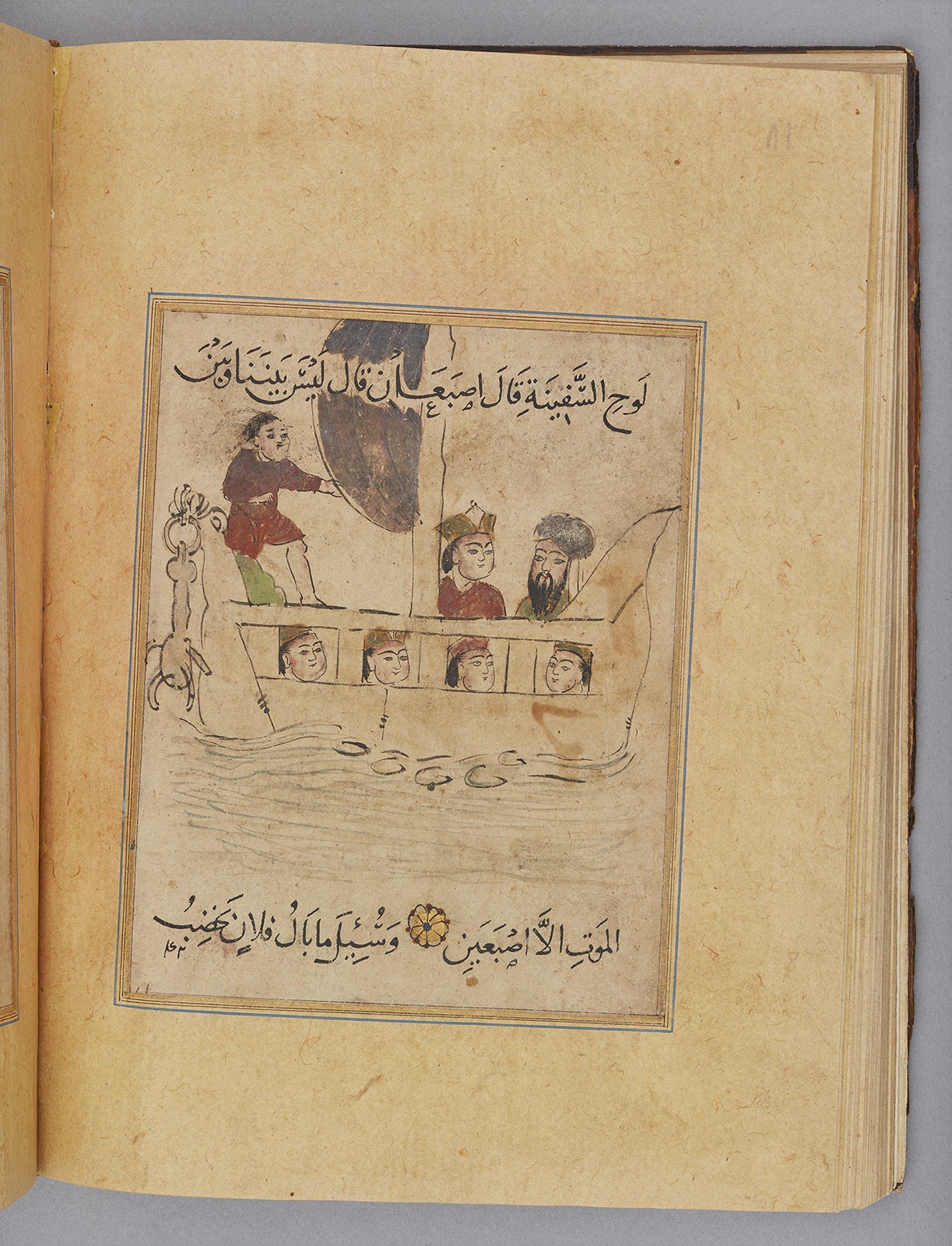

The illustrations of the manuscript are generic representations; indeed, eight depict a pair of male figures in conversation. Some connection to the text can, however, be found in several illustrations: for example, in the depictions of Iskandar, who is represented as an enthroned ruler (fol. 19r); of Hippocrates taking the pulse of a patient (fol. 23v); of the two woodcutters (fol. 30r) and the bare-headed Diogenes casually reclining (fol. 31v); of a sword-bearing man behind the philosopher who had taken a vow of silence (fol. 38v), and of the boat representing the hazards of the sea or life in general (fol. 41v).

The text in folio 41v refers to the maxim, “the distance between life and death is as wide as two fingers.” It comments that while sailing in calm seas, life-threatening waves can appear in an instant. The illustration shows a turbaned sage conversing with a youth in a sailing boat.

— Lale Uluç

Notes

[1] AKM283, colophon: “Katabahu Yaqut al-Musta‘simi” (Yaqut al-Musta‘simi wrote it); the signature of the artist: “Sawwarahu Mahmud b. Abi al-Mahasin al-Qashi hamidan Allahu ta‘ala ‘ala ni‘mihi wa musalliyan ‘ala nabiyyihi Muhammadin wa al-tahirin” (Mahmud b. Abi al-Mahasin al-Qashi illustrated it with thanks to God and with blessings to his prophet Muhammad and the pious ones).

[2] AKM283 has 46 folios (20.6 cm x 15 cm) written in 8 lines of naskh (11.9 cm x 8.9 cm) per page within gold and blue ruled frames (12.6 cm x 9.5 cm).

[3] The brown leather binding of the manuscript is not original. Its outer covers were produced in the Islamic world, however, and most probably in the Ottoman lands. Its gilded and sunk central oval medallion with endpieces above and below named salbek appears to be Ottoman and can be stylistically attributed to some time between the 16th and the 18th century. Its doublures are covered by plain paper. F. Çağman explains that the central medallions on Ottoman bindings became oval during the 16th century; see Filiz Çağman, “L’Art de la Reliure,” Soliman le Magnifique, exhibition catalogue, 15 February – 14 May 1990, Galleries Nationales du Grand Palais (Paris: Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, 1990), 314–5.

[4] Two are closely related to AKM283.

[5] The story states that he could copy the work of Yaqut al-Musta‘simi and send it to be sold at the bazaar, where no one could tell the difference. It is relayed by the Ottoman bureaucrat and historian Mustafa Ali; see Esra Akın-Kıvanç, ed., trans., and commented, Mustafa ‘Ali’s Epic Deeds of Artists: A Critical Edition of the Earliest Ottoman Text about the Calligraphers and Painters of the Islamic World (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011), 204.

[6] Mesihi, Gül-i sad-berg: Münşe’at, Istanbul, Süleymaniye Library, Esad Efendi, Letter (Mektup) no. 40. I would like to thank Nenad Filipović for bringing this letter to my attention. He hopes to prepare a detailed study and critical edition of this document to be published in the future. It is, in itself, a very important source for the study of Ottoman cultural and intellectual history.

[7] Nihat Çetin, İslam Ansiklopedisi, vol. 13, s.v. “Yâkut Musta‘simî”; David James, The Master Scribes — Qur'ans of the 10th to 14th Centuries, ed. Julian Raby (London: The Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press, 1992), 58–59; Nourane Ben Azzouna, “Manuscripts Attributed to Yaqut al-Musta’simi in Ottoman Collections – Thoughts on the Significance of Yaqut’s Legacy in the Ottoman Calligraphic Tradition,” Thirteenth International Congress of Turkish Art, ed. Géza David and Ibolya Gerelyes (Budapest: Hungarian National Museum, 2009), 113–9. Nihat Çetin, who has studied many examples signed with the name Yaqut, after mentioning that his students duplicated his calligraphies including his signature, adds that while some specify this fact and sign their own names as well, others have omitted to add their own signatures. He explains that this practice was then continued by the students of his initial six pupils, as well as drawing attention to the fact that some examples carry dates, which are much later than Yaqut’s year of death. Nourane Ben Azzouna, who has studied Yaqut al-Musta‘simi’s calligraphy, speculates that in his Qur’ans, he did not sign by the name Yaqut b. ‘Abdallah and provides an anthology of prayers in Istanbul Süleymaniye Library (Ayasofya 2775), signed Yaqut b. ‘Abdallah as a Timurid forgery; see Ben Azzouna, “Manuscripts Attributed to Yaqut al-Musta’simi,” 115–6.

[8] Late 13th- and 14th-century manuscripts comprising maxims in Arabic attributed to various personages, as well as the numerous examples of such maxims that were collected in the 15th and 16th centuries, in albums from the Turco-Persian world, attest to the tradition of collecting such texts that stretches back at least to the Abbasid period.

[9] Henri Massé, The Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed., vol. 1, s.v. “Buzurgmihr”; Aḥmad b. ‘Umar b. ‘Ali Nizami [‘Aruzi] Samarqandi, Chahar Maqala, ed. Muhammad Qazvini (Tehran: Armaghan, 1327), 22, cited by David J. Roxburgh, “Baysunghur’s Library: Questions related to its Chronology and Production,” Journal of Social Affairs (Shuun ijtimaiyah) 18.72 (2001): 29.

[10] D. Sourdel, The Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed., vol. 1, s.v. “Bayt al-Hikma.”

[11] Thomas W. Lentz, “Painting at Herat under Baysunghur ibn Shah Rukh,” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1985, 125; David J. Roxburgh, “"Our Works Point to Us": Album Making, Collecting and Art (1427-1565) Under the Timurids and Safavids,” Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1996, 1: 71–2.

[12] Examples are: Istanbul Süleymaniye Library, Ayasofya 4306, Nuruosmaniye 4907, Fazıl Ahmed Paşa 1205, Ayasofya 3764, Ayasofya 3765.

[13] The inventory includes many translations of the works of Greek scholars as well as a copy of the Pseudo-Aristotelian Advice for Alexander; see Necipoğlu, Kafadar, and Fleischer, eds., Treasures of Knowledge, 50, 54, 100, 440, 515–7, 529–30; for Aristotle’s advice to Alexander in the inventory, see 231 {8}, 231 {8}, 234 {12}, 251 {13}, 264 {4–5}, 145 {11–13}, 197 {17–19}, 198 {6, 11–13}; for collections of maxims in Arabic from the inventory, see 606–7 and 623–24.

[14] For a catalogue of the contents of the album, see Roxburgh, “Our Works Point to Us,” 2: 410–88. Also see David J. Roxburgh, The Persian Album, 1400–1600. From Dispersal to Collection (New Haven–London: Yale University Press, 2005), 68–86. For the intact scroll pieces in the album, see Lâle Uluç – Bora Keskiner, The Shah Tahmasp Album from the Istanbul University Library (forthcoming).

[15] For references, see Richard Ettinghausen, Arab Painting (Geneva: Skira, 1962).

[16] Marianna Shreve Simpson, “The Role of Baghdad in the Formation of Persian Painting,” Art et Société dans le Monde Iranien, ed. C. Adle (Paris: Institut Française d’Iranologie de Téhéran, 1982), 91–116.

References

Aḥmad b. ‘Umar b. ‘Ali Nizamī [‘Arużi] Samarqandi. Chahar Maqala, ed. Muhammad Qazvini. Tehran: Armaghan, 1327.

Akın-Kıvanç, Esra, ed., trans., and commented. Mustafa ‘Ali’s Epic Deeds of Artists: A Critical Edition of the Earliest Ottoman Text about the Calligraphers and Painters of the Islamic World. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011, 204. ISBN: 978900417872

Andı, M. Fatih. Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi, vol. 31, s.v. “Mustafa Sıdkı.”

Ben Azzouna, Nourane. “Manuscripts Attributed to Yaqut al-Musta’simī in Ottoman Collections – Thoughts on the Significance of Yaqut’s Legacy in the Ottoman Calligraphic Tradition,” Thirteenth International Congress of Turkish Art, eds. Géza David and Ibolya Gerelyes. Budapest: Hungarian National Museum, 2009, 113–9. ISBN: 9789637061653

Çağman, Filiz. “L’Art de la Reliure,” Soliman le Magnifique, exhibition catalogue, 15 February – 14 May 1990, Galleries Nationales du Grand Palais. Paris: Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, 1990. 314–5.

Çetin, Nihat, İslam Ansiklopedisi, vol. 13, s.v. “Yakut Musta‘simi.” The Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, 1986–2004. ISBN: 9789047412007

Erünsal, İsmail. Osmanlı Vakıf Kütüphaneleri. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları, 2008. ISBN: 9789751620514

Ettinghausen, Richard. Arab Painting. Geneva: Skira, 1962.

İpşirli, Mehmet. Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi, vol. 34, s.v. “Şah.” İslam Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: Milli Eğitim Basımevi, 1978–86.

James, David. The Master Scribes — Qur'ans of the 10th to 14th Centuries, ed. Julian Raby. London: The Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press, 1992, 58–9. ISBN: 9780197276013

Kütükoğlu, Mübahat S. Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi, vol. 34, s.v. “Pençe.”

---. Osmanlı Belgelerinin Dili (Diplomatik). Istanbul: Kubbealtı Neşriyat, 1994, 76–9.

Lentz, Thomas W. “Painting at Herat under Baysunghur ibn Shah Rukh,” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1985.

Massé, Henri. The Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed., vol. 1, s.v. “Buzurgmihr.” ISBN: 9789047412007

Necipoğlu, Gülru, Cemal Kafadar, and Cornell H. Fleischer, eds. Treasures of Knowledge: An Inventory of the Ottoman Palace Library (1502/3-1503/4), 2 vols. Leiden: Brill, 2019. ISBN: 9789004402485

Pakalın, Mehmet Z. “Pençe,” Osmanlı Tarih Deyimleri ve Terimleri Sözlüğü. Istanbul, Milli Eğitim Basımevi, 1946, 2: 769–71.

Pormann, Peter E. “Arabo-Islamic Tradition,” The Cambridge Companion to Hippocrates, ed. Peter E. Pormann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018, 340–62. ISBN: 978110770578

Roxburgh, David J. “"Our Works Point to Us": Album Making, Collecting and Art (1427–1565) Under the Timurids and Safavids,” Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1996.

---. “Baysunghur’s Library: Questions related to its Chronology and Production,” Journal of Social Affairs (Shuun ijtimaiyah) 18.72 (2001): 11–41/300–330.

---. The Persian Album, 1400–1600. From Dispersal to Collection. New Haven–London: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN: 9780300103250

Simpson, Marianna Shreve. “The Role of Baghdad in the Formation of Persian Painting,” Art et Société dans le Monde Iranien, ed. C. Adle. Paris: Institut Française d’Iranologie de Téhéran, 1982, 91–116. ISBN: 9782865380381

Sourdel, D. The Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed., vol. 1, s.v. “Bayt al-Hikma.” ISBN: 9789047412007

Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: ISAM, 1988–2016.

Uluç, Lâle and Bora Keskiner. The Shah Tahmasp Album from the Istanbul University Library (forthcoming).

Uzunçarşılı, İsmail H. “Tuğra ve Pençeler ile Ferman ve Buyuruldulara Dair,” Belleten 5/17–18 (1941): 101–57.

Von Kraelitz-Greifenhorst, Friedrich. “Studien zur osmanischen Urkundenlehre. Die Handfeste (Penče) der osman Wesire,” Mitteilungen zur Osmanischen Geschichte 2 (1923–1926): 257–69.

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.