Click on the image to zoom

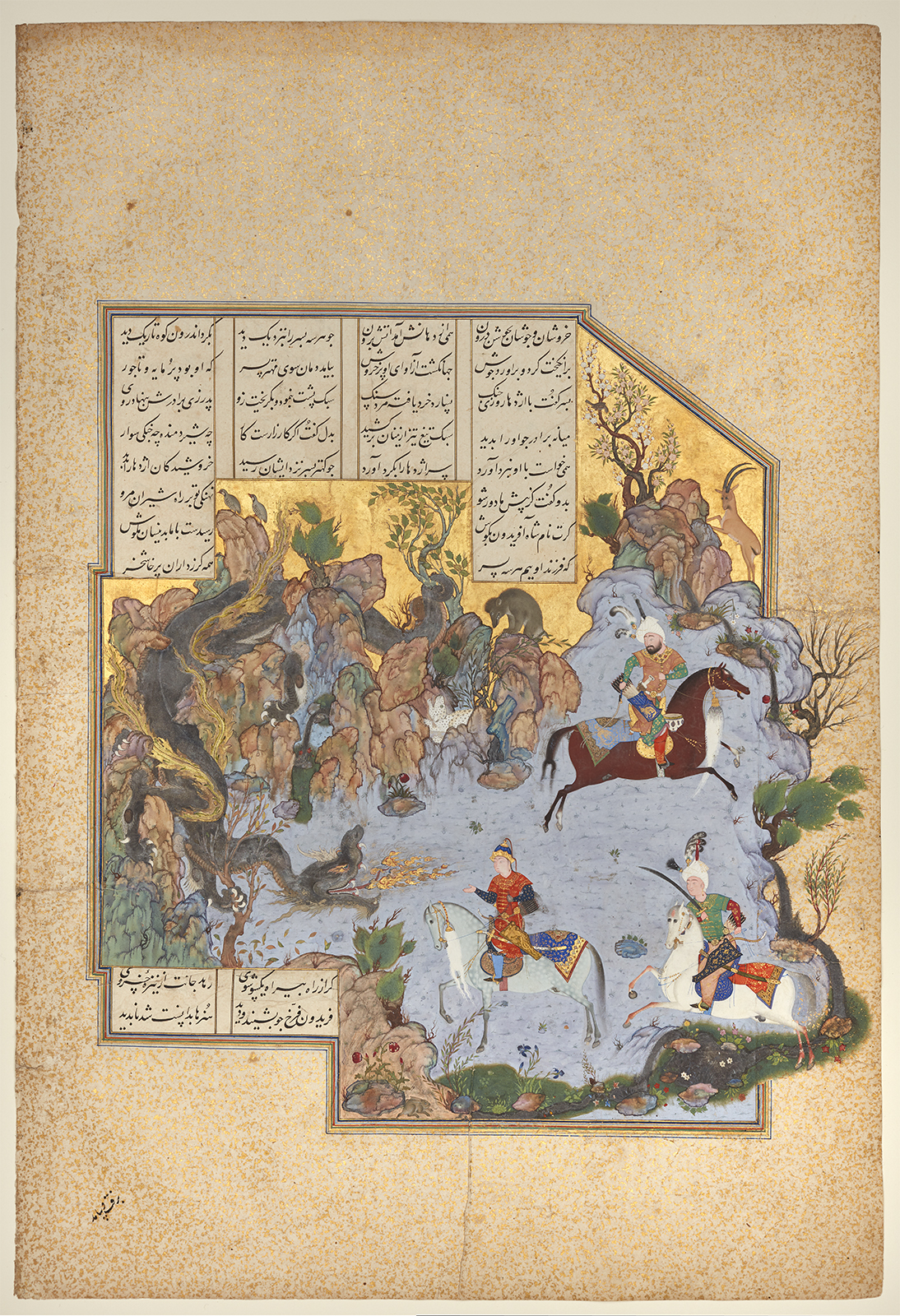

Faridun Tests his Sons

Folio form the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

- Accession Number:AKM903

- Creator:Attributed to Aqa Mirak

- Place:Iran, Tabriz

- Dimensions:47.2 x 32 cm

- Date:ca. 1535

- Materials and Technique:Opaque watercolour, gold and ink on paper

Firdausi’s epic poem the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), completed in 1010, recounts the history of all of Iran’s shahs (kings) up to the Arab conquest in 642 AD and the country’s adoption of Islam. It inspired countless works of art in all media, including the Shahnameh produced for Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), for which this folio AKM903 (folio 42 verso) was created. Here, the epic returns to the figure of Faridun, who had immobilized Zahhak (see AKM155) and later wed the two daughters of King Jamshid. They bore him three sons, but he declined to name them until they had matured and married. In order to ascertain his sons’ true characters, Faridun took the form of a fire-breathing dragon.

See AKM155 for an introduction to The Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

Further Reading

Attributed to Aqa Mirak, this painting displays a mastery of pictorial space.[1] The arc of the dragon on the left is offset by the placement of the three figures on horseback, guiding viewers through the painting from the lower centre to the upper right. In this way, viewers not only focus on the primary encounter between rider and dragon in the painting’s foreground, but also explore the reactions of the other two riders. The differences among them are crucial. At the sight of the dragon the oldest son turns and flees, exclaiming that no sane person would fight a dragon. The middle son prepares to fight the beast as if he were in battle with another man. The youngest son stands his ground, telling the dragon to be off because he and his brothers are the sons of Faridun and warriors like their father. Faridun calls the first one Salm because he had sought safety; the second he names Tur for his brash fearlessness; and the third, who astutely and bravely confronted the dragon, is dubbed Iraj. To each Faridun assigns one third of his kingdom. Salm receives Rum, the western provinces; Tur receives the eastern section, Turan; and Iraj is given the central kingdom, Iran.

The faces of Faridun’s sons reflect their age and personalities. Salm’s beard signals his relative maturity in years while his raised eyebrows and popping eyes express his great alarm at the sight of the dragon. Tur, sporting a thin moustache, leans forward, brandishing his sword and staring at the beast. The beardless face of Iraj indicates his youth, but his extended hand, erect posture and calm face underline the notion of his brave, yet composed character. Each figure and his horse are silhouetted on a pale lavender blue ground ringed by rocks and a cascading mountain stream. The contrast between multicoloured, jutting rocks through which the dragon glides and the arid turf beneath the horses’ hooves mirrors the wild ferocity of the dragon versus the tame horses and the men who ride them. As in the paintings of Sultan Muhammad (such as “The Court of Kayumars,” AKM165), the rocks themselves are here teeming with hidden grotesque faces as well as real animals—ibex, snow leopard, bear, partridge and, in the foreground, a rabbit—which roar, cower or observe the drama unfolding before them. Aqa Mirak seems to synthesize elements of Sultan Muhammad’s work with the harmonious compositions gleaned from the Herat master Bihzad and his followers.

Descended from a family of sayyids (descendants of the Prophet Muhammad) from Isfahan, Aga Mirak was “an incomparable painter, very clever, enamored of his art, a bon vivant, an intimate (of the Shah), and a sage.”[2] Most likely he was close in age to Shah Tahmasp, who recognized his talent by eventually appointing him to the important post of chief purveyor of materials for the royal library.

The Shahnameh produced for Shah Tamasp is represented in the Aga Khan Museum Collection by ten paintings (AKM155, AKM156, AKM162, AKM163, AKM164, AKM165, AKM495, AKM496, AKM497, AKM903) out of a total of 258 illustrations in the original manuscript.

— Sheila R. Canby

Notes

[1] For a discussion of the spatial challenges in this painting, see Dickson and Welch, vol. 1, 105.

[2] See Qadi Ahmad/Minorsky, 185.

References

Ahmad, Qadi. Calligraphers and Painters, trans. V. Minorsky, 185. Washington, D. C.: Freer Gallery, 1959. ISBN: 9780934686068

Dickson, Martin B. and Stuart Cary Welch. The Houghton Shahnameh, 2 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981. ISBN: 9780674408548

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.