Click on the image to zoom

Dala’il al-Khayrat Prayer book

- Accession Number:AKM278

- Place:Probably Kashmir

- Dimensions:13.6 x 8.5 x 2 cm

- Date:dated A.H. Muharram 1233/AD November 1818

- Materials and Technique:lacquer binding; opaque watercolour, ink, and gold on paper

This manuscript is a very fine copy of a Dala’il al-Khayrat prayer book. It has previously been identified as Ottoman, but it reflects the tradition of Dala’il al-Khayrats from Kashmir and general manuscript production from that region. [1] Its text was composed in the mid-15th century in Morocco by Moroccan mystic and sufi Muhammad (born Sulayman al-Jazuli; d. 1465) and consists of a manual of devotion for the prophet Muhammad. Dala’il manuscripts gained popularity beginning in the 16th century and were copied from Senegal to Eastern China, becoming the most popular Islamic devotional work after the Qur’an.

Further Reading

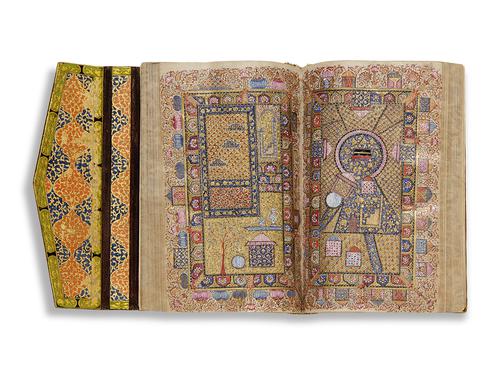

Both the text of the Dala’il and its artistic treatment exist in many variations. This example from the Aga Khan Museum Collection reveals the sophistication of Kashmiri Dala’il production. The manuscript is bound in a gold and brown lacquer binding with floral repertoire and cloud-band motifs, composed with central medallion and large spandrels in the corners. The inner covers have a blue background with red cartouches overlaid with delicate gold filigree. Ten richly illuminated double-pages decorate the beginning of individual sections.

The codex comprises 213 folios and several blank pages at the beginning and the end. The text is written in Arabic, fully vocalized, with either eleven or five lines per page in black naskhi script. It includes an introductory section, with instructions entitled al-hajati (“needs”) of the duration (from Sunday to Saturday) and the rituals of reciting the Dala’il; a section on the virtue of invoking the blessings of the prophet; a list of the holy names and titles of the prophet; and the description of the blessed garden in Medina (sifa al-rawd a al-mubaraka), where he is buried next to his companions ‘Abu Bakr and ‘Umar. These short sections are followed by the body of the text, which contains blessing prayers upon the Prophet. Here, such prayers are divided in seven ritual hizbs (ahzab) or sections, allotting one section per day for a period of a week starting on a Sunday. This organization deviates from the more common division into eight sections, for prayers from Monday through Monday.

The layout and designs of illumination and ornamental panels in this codex have both a decorative and functional goal. The ornamental sign language is hierarchically organized and guides the reader through passages and sections. Important chapters—such as the opening of the book, the part introducing the waymarks of the Dala’il al-Khayrat, or the seven individual ritual sections (hizbs)—begin with an elaborately illuminated jadwal-double-page. The text block is limited to five lines, while prominence is given to a stylized four-leaf clover pattern covering the entire surface. The individual leaves are pointed, their corners filled with a fleur-de-lis-like pattern that is delicately decorated with small leaves and floral motifs, all in alternating shades of gold and lapis blue surrounded by a border with repeating drops highlighted in red. Except for the opening double-page with empty cartouches, each of these illuminated jadwal-compositions bears a calligraphic title-cartouche referring to the part in question (For example al-hizb al-awwal …, al-hizb al-sabi‘a). Black annotations in the margin of these decorative jadwals indicate which day of the week the ritual/section the reader should recite.

A less prominent decorative layout feature subdivides individual chapters. For example, within the introductory part (first jadwal), the instructions of when and how to recite the text are presented as a title inserted in a line of the continuous text. Al-hajati (pages 9 and 10; what is necessary/instructions) is written in the centre with a small gold floral ornament on each side. In addition, between the inner and outer margins, a gold paisley-like motif with a diagonal red note inscribing the day of ritual guides the reader; six such decorative paisley marks exist in these instructions. The part listing the names and titles of the Prophet is marked with an illuminated calligraphic horizontal panel inserted within the inner margins (pages 57–58); this sub-section is included in the second part, hadha Kitab Dala’il al-Khayrat. Between the individual names and epithets are small gold circles outlined in black, which probably refer to the eulogy of the Prophet salla llahu ‘alaihi wa-sallam (May God bless him and give him Salvation), to be repeated during recitation.[2]

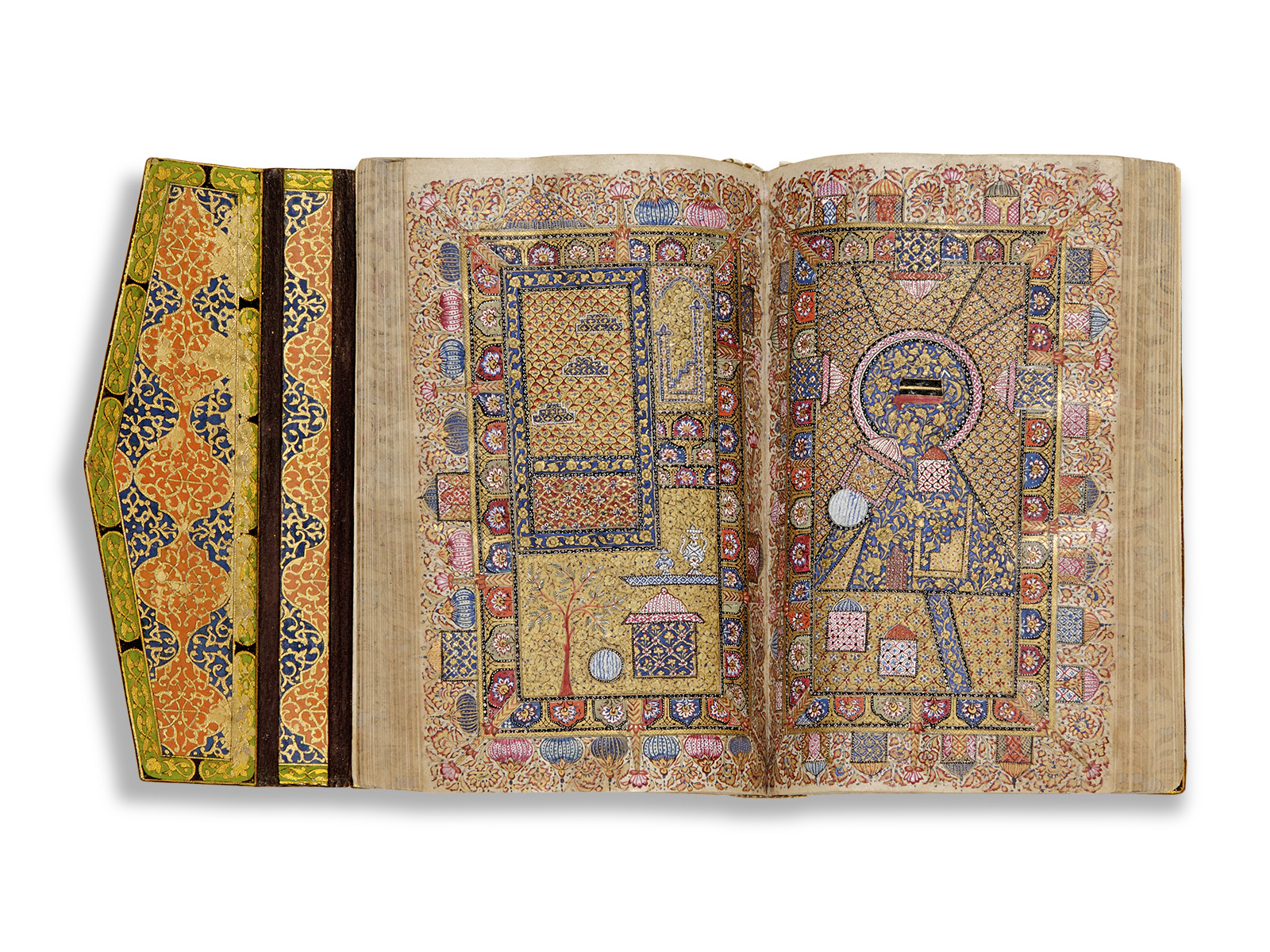

Other decorative calligraphic title panels within the ritual sections reflect an older division of the prayers in quarters, thirds, and a half, often kept in Dala’il manuscripts.[3] Red and blue inks are used to throughout the text to indicate important passages. For example, in the description of the blessed garden in Medina with the tomb of the Prophet and his two companion, the two first words, wa hadha (and this is…) are in blue and visually distinguish this passage from the otherwise continuous black text. It is followed by a double-page depiction of the two holy cities of Mecca (on the right) and Medina (on the left) (fig.1).

Typical for Kashmiri Dala’il al-Khayrat works, these sacred sites are composed in a two-dimensional style. Architectural elements and other details are arranged within rectangular fields evoking bento boxes. A concentric composition—using circles within circles—increases the focus and sanctity of these two holy cities. Mecca is represented on the upper right side with the keyhole motif enclosing the Ka‘ba, indicated as a small rectangle above and the minbar or pulpit below, the various maqams or pavilions (including the four legal schools of Islam) surrounding it. Medina is depicted on the left side with three diagonally succeeding tombs—one for the Prophet and two for his companions—on the upper left side and the minbar on the right within a many-lobed arch. In the lower half is tomb of the Prophet’s daughter Fatima, in the garden that she planted with a palm tree when her father was alive; all is symbolizing the gardens of the Prophet’s tomb. Next to it on the left are the water dwell (represented as a conventional circle) and the tomb of Fatima (shown as a domed building). Typical for Kashmiri copies, small but delicately rendered details, such as an ewer, are also included in the composition. The palette is rich, varying from blues and reds to green, white and gold. Intricately detailed and often floral ornamentation covers or alternates with buildings and fills the background, rendering this double-page a large and precious garment or tapestry. See AKM382, AKM535 and AKM278 for examples of Dala’il al-Khayrat prayer books in the Aga Khan Museum Collection.

— Deniz Beyazit

Notes

[1] The full title is Dala’il al-Khayrat wa Shawariq al-Anwar fi Dhikr al-Salat ‘ala al-Nabi al-Mukhtar (Translation from Witkam 2007, 69: “Guidelines to the Blessing and the Shinings of Lights, Giving the Saying of the blessing prayer over the Chosen Prophet”). For previous publications with Ottoman attribution, see Welch 1972, p. 139; Architecture in Islamic Arts: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum, 2011.; The Path of Princes: Masterpieces from the Aga Khan Museum Collection, 2008.

[2] An Ottoman example dated 1848 in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York comprises such circles with Eulogy written in minuscule dust script (2017.438). These inscribed Eulogy circles are placed between the names of the prophet and confirm this interpretation. This interpretation is also proposed by Daub 2016, 151–58.

[3] Witcam 2007, 69. For example, the Ottoman Dala’il AKM382 has eight sections.

References

Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Architecture in Islamic Arts: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2011. ISBN: 9780987846303

---. The Path of Princes: Masterpieces from the Aga Khan Museum. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2008. ISBN: 9782940212022

Dalaʼil al-Khayrat : prayer manuscripts from the 16th to 19th centuries / writer, Nurul Iman Rusli ; advisor & editors, Dr. Heba Nayel Barakat. Kuala Lumpur 2016. ISBN: 9789832591122

Daub, Frederike-Wiebke. Formen und Funktionen des Layouts in arabischen Manuskription anhand von Abschriften religöser Texte Burda, al-Ğazūlīs Dalā’il und die Šifā’ von Qādī ‘Iyād (Arabische Studien 12). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2016. ISBN: 9783447106702

Falk, Toby. Treasures of Islam. London: Sotheby’s Publications, 1985. ISBN: 9780856671968

Welch, Anthony. Collection of Islamic Art, Vol. IV. Geneva: privately printed, 1972.

Wikam, Jan Just. “The battle of the images: Mekka vs. Medina in the iconography of the manuscripts of al-Jazuli’s Dala’il al-Khayra,” in Pfeiffer, Judith and Manfred Kropp, Theoretical Approaches to the Transmission and Edition of Oriental Manuscripts, Proceedings of a symposium held in Istanbul March 28-30, 2001. Beirut: Ergon Verlag, 2007, 67–82. ISBN: 978-3899135329

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.