Click on the image to zoom

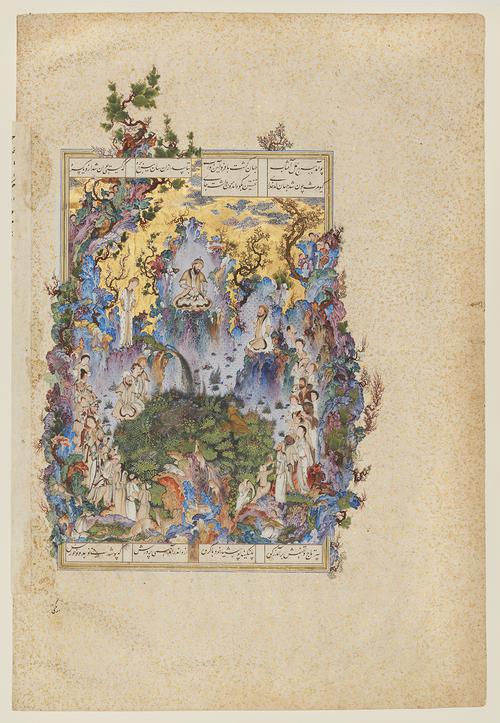

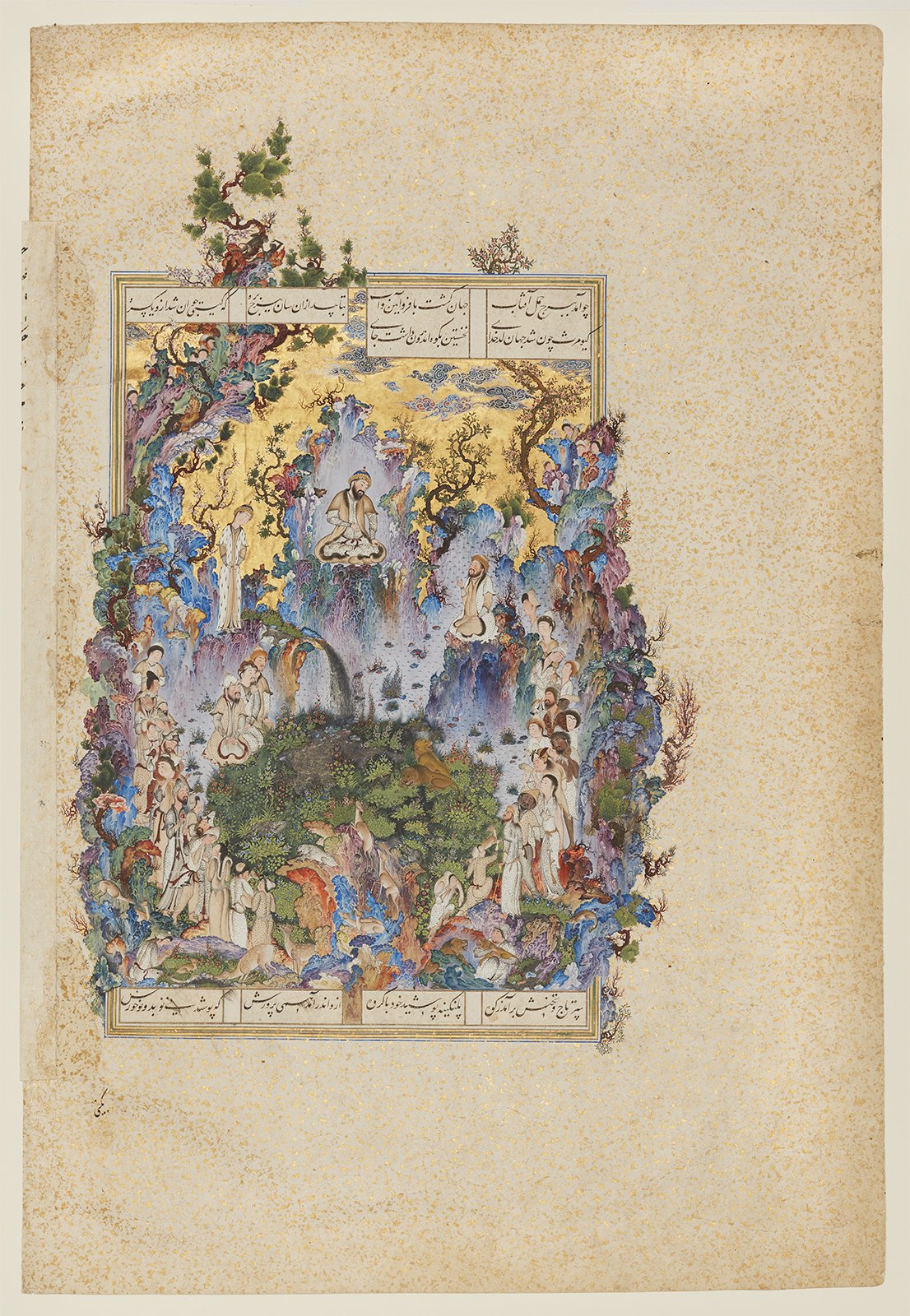

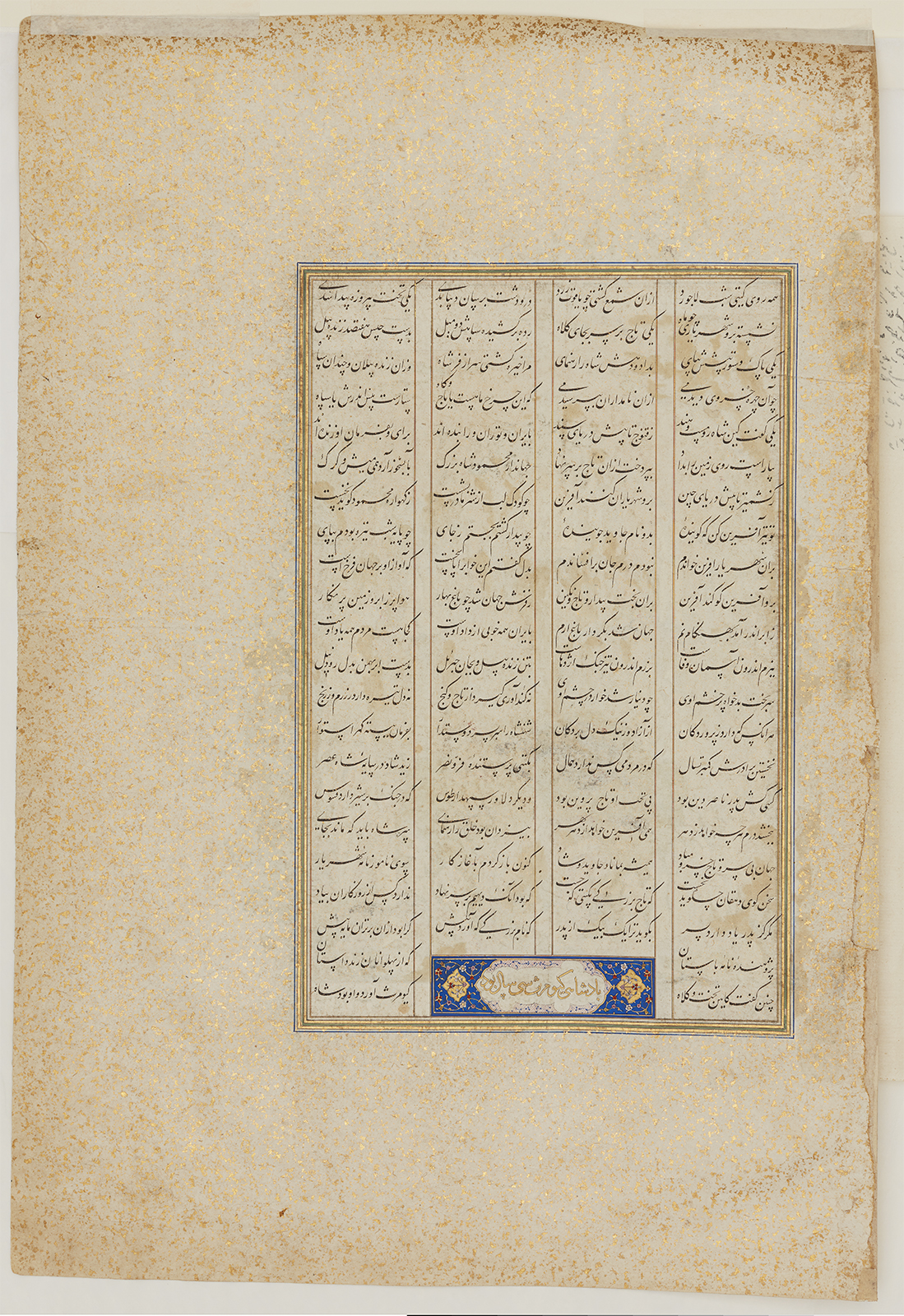

The Court of Kayumars

Folio from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

- Accession Number:AKM165

- Creator:Attributed to Safavid master Sultan Muhammad

- Place:Iran, Tabriz

- Dimensions:45 x 30 cm

- Date:ca.1524–1525

- Materials and Technique:Opaque watercolour, ink, and gold on paper

Firdausi’s epic poem the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), completed in 1010, recounts the history of all of Iran’s shahs (kings) up to the Arab conquest in 642 AD and the country’s adoption of Islam. A large part of the poem focuses on prehistoric, legendary kings, some of whom ruled for hundreds of years and established man’s knowledge of everything from fire to weaving. According to Firdausi, the very idea of kingship originated with King Kayumars, who ruled for thirty years, overseeing a peaceable kingdom in which men wore leopard-skin robes and wild animals grew tame. In this utopia Kayumars had one secret enemy, the evil Ahriman, whose envy drove him to incite his own son, the Black Div, to murder Siyamak, the son of Kayumars. Before the assassination took place, the angel Surush warned Kayumars of Ahriman’s plot.[1]

See AKM155 for an introduction to The Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

Further Reading

Of the 258 Shahnameh illustrations produced for Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-76), the second shah of the Safavid dynasty, “The Court of Kayumars” AKM165 (folio 20 verso) is arguably the most magnificent. It is attributed to Safavid master Sultan Muhammad, a native of Tabriz who worked in the Safavid royal library and was employed to teach painting to Shah Tahmasp upon his return from Herat in 1522. It may be the only 16th-century work that is mentioned specifically by a Safavid writer. In the words of Dust Muhammad, who compiled an album of pictures and calligraphy for Shah Tahmasp’s brother, Bahram Mirza, “[the painting] is such that the lion-hearted of the jungle of depiction and the leopards and crocodiles of the workshop of ornamentation quail at the fangs of his pen and bend their necks before the awesomeness of his pictures.”

“The Court of Kayumars” is exceptional for its complexity, its mastery of colour, the minute scale of its details, and the emotional intensity of its message. Kayumars, seated on a rocky throne, gazes toward his son, Siyamak. Standing across from Siyamak is the angel Surush, shown here regarding Siyamak as he warns Kayumars of Ahriman’s plot. The poignancy of the revelation that Kayumars’ beloved son is the target of this wicked scheme is expressed by his sharply focused contemplation and the finger he points in the direction of Siyamak.

The gold sky and the soaring landscape that extends into the margins of the painting on three sides elevate the viewer’s eye and spirit. The world it depicts is arcadian, one in which animals and humans live in harmony. Sultan Muhammad’s mastery and creativity are shown through the rendering of such textures as the soft fur of coat linings and caps; the splatter of water, now blackened, flowing from rock to stream; and the transition of blue rocks into green. Scores of human and animal faces inhabit the rocks, animating the painting. The wonder of Kayumars’ realm is also communicated through pairs of bears, deer and lions; frolicking monkeys; and a nestling cow and bull. However, in the triangle formed by the three protagonists lies the knowledge of the evil that will begin an eternal battle between good and evil.

Such an inspired work reaches far beyond the simple exigencies of illustrating a narrative. It reflects a spirituality and rare connection to nature through man, animal, plant and mineral, rarely, if ever surpassed in Persian painting.

The Shahnameh produced for Shah Tamasp is represented in the Aga Khan Museum Collection by ten paintings (AKM155, AKM156, AKM162, AKM163, AKM164, AKM165, AKM495, AKM496, AKM497, AKM903) out of a total of 258 illustrations in the original manuscript.

— Sheila R. Canby

Notes

[1] Sources such as Dickson and Welch, vol. 2, no, 7; Welch 1979, 50; and Canby, 48 identify the standing figure as Hushang, the son of Siyamak. However, he is not mentioned in the text until later, one year after the death of Siyamak. Although he wears a crown, he is described as wearing leopard-skin clothing and in “fairy-form.” Welch 1972, 88 correctly identifies this figure as Surush.

References

Canby, Sheila R. Princes, Poets and Paladins: Islamic and Indian Paintings from the collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan, 329–33. London: British Museum Press, 1998. ISBN: 9780714114835

Dickson, Martin B. and Stuart Cary Welch. The Houghton Shahnameh, 2 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981. ISBN: 9780674408548

Thackston, W.M. selected and translated, A Century of Princes: Sources on Timurid History and Art, 348. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989. ISBN: 9780922673117

Welch, Stuart Cary. A King’s Book of King’s: The Shah-Nameh of Shah Tahmasp. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1972. ISBN: 9780300192650

Welch, Stuart Cary. Wonders of the Age: Masterpieces of Early Safavid Painting, 1501–1576, no. 27. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. ISBN: 9780916724382

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.